.479ZUK stagnation turns to risk of double-dip recession

By Michael Burke

The Construction Products Association (CPA) is forecasting a ‘double-dip’ UK recession for the construction industry in 2012 and compares the latest slump to that of 10 years ago – the last Tory recession under Major when 600,000 construction industry jobs were lost. The CPA is well-placed to judge the near-term outlook as it comprises all the main suppliers to the construction industry.

For most of 2011 the majority of commentary on the British economy veered between expectations of a strong boom and, more recently projections for a double-dip recession. The reality was more prosaic – with the economy stagnating, growing by just 0.5% over the latest 12-month period.

This is because most commentators ignored the actual cause of the prior recovery and the key factor which would reverse it. SEB has previously shown how the recovery was caused by the increase in government spending, both current spending (mainly increased welfare payments but also the Labour government’s cut in VAT) and increased government investment (Building Schools for the Future, etc.).

Reversal of Government Spending

The renewed economic stagnation arises because both parts of government spending have now been cut. Welfare benefits have been cut, which is disastrous for many recipients but also undermines household consumption as does the hike in VAT. Household consumption is the biggest single category of GDP. The policies that supported household consumption added 1.2% to GDP growth during the recovery and until Labour left office. In the period since the Tories took office the decline in household consumption has reduced GDP by 0.6%. Similarly government investment increased under Labour and directly added 0.8% to GDP over the course of the recession. Government investment fell immediately the Tory-led Coalition took office and has subtracted 1.0% from GDP over that period.

Taken together the combined effects of Labour’s increased spending added 1.8% to GDP, while the policies of this government have subtracted 1.6% from GDP.

Effects of Changing Fiscal Stance

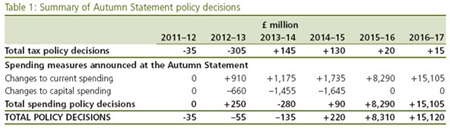

The March 2011 Budget detailed a ‘fiscal tightening’, that is tax increases (except for companies) and spending cuts amounting to £41bn. By the 3rd quarter approximately half of that tightening will have taken place as it is 6 months into the Financial Year. £41bn is approximately equivalent to 2.7% of GDP. The previous recovery saw the economy expand by 2.8% over 5 quarters. Therefore the direct effect of the fiscal tightening currently under way is to remove growth almost entirely from the economy, hence stagnation.

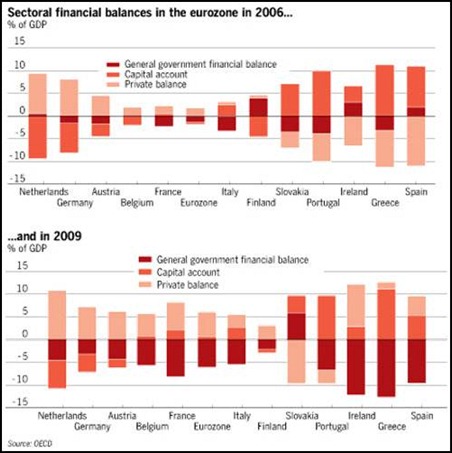

Unfortunately the extent of the damage does not end there. The fiscal tightening is only half-complete this year and yet there is already stagnation. This is because each sector of the economy is connected to the other. So, declining government spending in the form of firing public sector workers will lead to falling household consumption, and both will affect business investment.

Since each economic sector responds variably to a change in another sector’s activity, and often with a time lag, it is impossible to assign a precisely distributed causal effect of a change in fiscal policy. But we have noted above that Labour’s increased spending of 1.8% of GDP led to a recovery which added 2.8% to GDP. This demonstrates the way the state can lead economic activity in total. This is what Keynes called the ‘multiplier effect’ as the private sector responds to increased government spending. In this case the multiplier is 1.56 (the ratio of 2.8% to increased spending equal to 1.8% of GDP).

In reality the multiplier is probably considerably higher as there is a pronounced time lag while the business sector responds to changes in government spending. SEB has previously shown that private sector investment has consistently risen or fallen 6 months after changes in output. So, the private sector continued to invest for 6 months after the Coalition took office, and this was in response to the increased spending by the Labour government.

Therefore, without taking account of other factors such as net exports or an unwanted build-up of inventories, the direct and indirect impact of the current government’s cuts should be multiplied by 1.56. This would subtract 4.2% from GDP and almost certainly lead to renewed economic contraction. The government also plans £61bn of fiscal tightening in the next Financial Year, beginning in April.

Construction Investment

The construction sector is highly responsive to the business cycle as it relies on a high level of current investment. The CPA estimate that it is headed for a double-dip recession is therefore highly significant. This will sharpen the already acute shortage of affordable homes, either to buy or rent at a time when 300,000 construction workers have already been made unemployed. Local authorities throughout Britain are desperate for funds to build new homes, from which they could derive an income way above the cost of borrowing even with affordable rents. Instead of providing funds to them, George Osborne has provided £40bn in ‘credit easing’ to small and medium sized enterprises. They will not build homes, provide decent affordable housing and employ workers with these funds.

But the State could because it is a vastly more efficient provider of large-scale housing as well as infrastructure projects. The government and its supporters like to promote the falsehood that ‘there is no money left’. But £40bn of loans to local authorities and public bodies could go a long way to easing the housing crisis. It would also go some way to averting the likelihood of a double dip recession.

From the government’s perspective the only stumbling-block is that it would remove the main responsibility for construction from the hands of the private sector and place it in the hands of the public sector. This is of course what happened to most of the shareholder-held banking sector in Britain during the last crisis. It seems that nationalisation is only permissible when bondholders and shareholders are being rescued. But it is not allowed if it is to rescue the unemployed, those paying extortionate rents for substandard homes or even the economy as a whole.

Recent Comments