am, Victoria Square, Birmingham

- investment in public services, in infrastructure, and in decent jobs for all

- an end to scapegoating of migrants which divides our communities and whips up racism

Comment and analysis for the movement against austerity.

am, Victoria Square, Birmingham

Illusion of the narrowing trade gap

By Tom O’Leary

A recent Times editorial castigated the new International Trade Secretary Liam Fox for his foolish remarks regarding the laziness of British business executives. If The Times is going to criticise every stupid pronouncement by the three new ministers for Brexit, there will be little room for any other comment.

But the editorial also betrayed a lack of knowledge about elementary economics. And, as the assertions made about what prevents Britain being a greater or even an important participant in international trade are widely held, they are worth rebutting. The editorial states that,

“We should…complain about export growth. It is true that too few British companies succeed abroad. This is partly because they struggle to compete with rivals in India and China that spend less on wages. It is partly because companies selling services do not always find willing buyers in those markets. It is furthermore a reflection of lack of ambition.”

So, not laziness, but ‘lack of ambition’ and lower wages in India and China are the sources of British export weakness. This is plain nonsense.

The chart in Fig.1 below shows the level of total exports to the world from UK and from Europe’s export powerhouse Germany. In the most recent quarter UK exports to the world were valued at US$100bn while German exports were valued at US$326bn. Germany has a population about one quarter again as big as the UK and its economy is approximately 40% larger. Yet German exports are more than 3 times greater than those from the UK. Germany has struggled under the weight of slow global growth. Even so, Germany’s export performances is vastly greater than that of the UK economy, even though Indian and Chinese wages are just as low for German manufacturers as they are for British ones.

A key reason why German exports are more than 3 times greater than UK exports is that the German economy is much more integrated into global supply chains. This also means that Germany’s imports are also far greater than the UK’s. But Germany also provides a much higher level of value added to the imported raw materials and inputs of intermediate and capital goods. By contrast the UK is more usually the final destination of its imports, the final consumer of goods not the final producer of finished goods.

Currency Devaluations

The widely expressed hope is that the devaluation of the pound will lead to a revival of exports. Sterling’s trade-weight currency index (a basket of currencies weighted according to UK trade) has fallen by around 10% since just before the Brexit referendum and has fallen by 18% since mid-November 2015.

Currency devaluations can boost exports. They also raise the price of imports and so lowers the living standards of the population. Viewed domestically, devaluations represent a transfer of incomes from consumers to producers.

Exporters benefit because their key cost is now lower in international terms, wages. Other inputs such as energy and raw material, as well inputs of semi-finished or intermediate goods produced abroad will all eventually rise to adjust to the new exchange rate.

The long run history of the British economy is punctuated by repeated and very sharp devaluations. Yet Britain’s share of world trade has continued to decline and is now a fraction of former competitors such as Germany.

The devaluations are a product of economic weakness driven by underinvestment. UK exporters have not responded to devaluations with increased investment, but have simply temporarily increased profit margins. As competitors continue to invest at a greater rate this cost advantage is eroded and the cycle of declining competitiveness and devaluations sets in once again.

Will this time be different? There is no evidence that it will be. The British Chambers of Commerce is just the latest organisation to forecast reduced business investment in the period ahead. This follows similarly gloomy forecasts from the Bank of England, Markit Purchasing Managers surveys, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in the England and Wales, as well as others.

The structural impediment is that the UK economy is not sufficiently integrated into global supply chains. With a few exceptions, such as aerospace, cars and a small number of others, UK industry is not part of the leading European or global industrial sectors. There is no other route to increasing that participation other than increased trade links with the rest of the world based on significantly increased industrial investment (not increased bluster from the Tory Ministerial Brexiteers).

The latest international trade data showed a narrowing of the trade gap, Fig.3 below. The much-heralded rise in exports in the data, held to vindicate Brexit, is simply an exchange rate illusion. Most trade internationally is conducted in US Dollars. The falling level of the pound against the US Dollar raises the value of exports in Pound terms, which is how the trade data is naturally reported.

But the ONS also reports trade data on a volume basis. In July, following the devaluation the total volume of UK exports fell 0.2% from June and were just 1.1% higher than a year ago. The narrowing of the trade gap arose from a 3.8% fall in import volumes from June, and they were just 1.2% higher than a year ago.

There is no evidence to date that exports will rise on a sustained basis following the devaluation. It is possible that the trade balance will narrow for a period because incomes have fallen on an international purchasing power basis, poorer firms or households cannot afford the same level of imports. The trade gap may narrow, but only because the UK is poorer. Using the weakness of the pound to improve living standards would require an investment-based reindustrialisation strategy.

The ‘Golden Age’ and the Public Sector Deficit

John McDonnell’s fiscal policy framework continues to come under fire from both left and right. The framework broadly states that the Government should borrow for investment (the capital account) and that over the business cycle Government day-to-day spending (the Government’s current account) should be in balance.

The attacks from the right are largely disingenuous. They argue that the McDonnell framework is little different from that of Ed Balls, a cloak for austerity-lite. The Balls approach also included a commitment to match Tory spending plans in the first two years. These would have been the deepest cuts to public spending in history and were so draconian that the Tories themselves abandoned them in office after May 2015. Balls supplemented this with a ‘zero-based spending review’, that is a commitment to have no commitments, not even to pensions, to social welfare for disabled people, or to the NHS.

The contrast with John McDonnell is a sharp one. He has consistently opposed austerity. Crucially, McDonnell he has committed to the establishment of a National Investment Bank to address the acute investment shortage of the UK economy. He has also committed to borrowing £500 billion for investment to tackle the crisis. The McDonnell framework is not different to Balls because it can be suspended. Its content and its effects would be entirely different.

‘Keynesian’ misunderstanding

Unfortunately, because of a deep misunderstanding of economics, economic history and public finances, many progressive or ‘keynesian’ economists echo these same rightist criticisms. As this is primarily misunderstanding not malevolence, it is worth addressing once again.

From a theoretical perspective the misunderstanding arises because of the widespread view that Consumption can lead growth. Therefore, it is argued, the Government should increase its own Consumption in order to foster recovery. The premise is false.

Consumption cannot lead growth because it is not an input to it. Consumption is a consequence of production, and growing Consumption is a consequence of growing production. If production has not risen increased Consumption requires borrowing, which is a financial claim on future production. Furthermore, if an increasing proportion of output is devoted to Consumption rather than Investment the growth rate of the entire economy will slow, and so too will Consumption.

Yet ‘keynesians’ and other progressives who wish to end austerity persist in arguing for Government to increase Consumption by borrowing on its own account- hence the attacks on McDonnell. This is also flies in the face of economic history.

History

It is widely recognised the economic growth rate of the UK and of many of the Western economies was greater in the post-World War II period, from 1945 to the early 1970s than in the subsequent period. This recognition includes ‘keynesians’ and many others, some describing it as the ‘Golden Age’.

This itself is a misreading as the far higher growth rate in the US and to a lesser extent the UK was in the pre-war and war period itself. The exceptionally strong growth was caused by the state taking control of investment and directing very large increases, in order to wage war. The subsequent ‘Golden Age’ was the gradual deceleration of this war boom.

Even so, the recognition that growth in the post-War period was markedly stronger than the period beginning in the early 1970s is shared. It is factually correct. Yet this ‘Golden Age’ does not at all conform to the ‘keynesian’ prescription for permanent public sector deficits on the current Budget. In fact it shows the opposite.

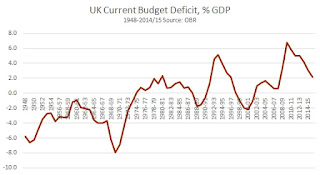

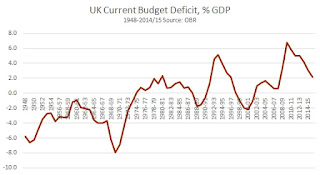

In Fig.1 below the UK Current Budget Deficit is shown as a proportion of GDP. A level above zero shows a deficit. Below zero shows a surplus. For the entire period of the ‘Golden Age’ the UK Current Budget was not just balanced, it was in surplus.

This post-WWII period of large current Budget surpluses coincided with the establishment of the NHS, the creation of the ‘welfare state’, a massive public sector house building programme, large scale nationalisations and other measures.

How is this possible? How can there both be (sometimes huge) surpluses on the current Budget while Government current spending was initiating a whole series of new or improved public goods?

The answer is investment, public investment. Fig.2 below shows the level of Public Sector Net Investment as a proportion of GDP over the same period.

This explains why both rightist and leftist criticisms are misplaced. The McDonnell framework will not lead to austerity if investment is increased. More importantly, it offers a way out of the crisis. If investment is sufficiently strong the economic recovery will provide sufficient tax revenues and lower social security outlays to become self-sustaining. This improvement in government finances can be used for more investment and for increased current spending.

On the other hand, if it should be the case that recovery remains weak and therefore the current budget remains in deficit, then the answer would not be to cut current spending, but to increase public sector investment.

The period of the greatest advances in public sector current spending took place when there were surpluses on this current account, only made possible by relatively high levels of public investment, in British terms at least. Current spending has been in crisis ever since 1974, with Denis Healey’s fake IMF crisis, then Thatcher and her successors, who slashed public investment.

Mainstream economics largely tries to bury economic history. Those genuinely seeking an alternative to austerity should not make the same mistake.

The ‘Golden Age’ and the Public Sector Deficit

John McDonnell’s fiscal policy framework continues to come under fire from both left and right. The framework broadly states that the Government should borrow for investment (the capital account) and that over the business cycle Government day-to-day spending (the Government’s current account) should be in balance.

The attacks from the right are largely disingenuous. They argue that the McDonnell framework is little different from that of Ed Balls, a cloak for austerity-lite. The Balls approach also included a commitment to match Tory spending plans in the first two years. These would have been the deepest cuts to public spending in history and were so draconian that the Tories themselves abandoned them in office after May 2015. Balls supplemented this with a ‘zero-based spending review’, that is a commitment to have no commitments, not even to pensions, to social welfare for disabled people, or to the NHS.

The contrast with John McDonnell is a sharp one. He has consistently opposed austerity. Crucially, McDonnell he has committed to the establishment of a National Investment Bank to address the acute investment shortage of the UK economy. He has also committed to borrowing £500 billion for investment to tackle the crisis. The McDonnell framework is not different to Balls because it can be suspended. Its content and its effects would be entirely different.

‘Keynesian’ misunderstanding

Unfortunately, because of a deep misunderstanding of economics, economic history and public finances, many progressive or ‘keynesian’ economists echo these same rightist criticisms. As this is primarily misunderstanding not malevolence, it is worth addressing once again.

From a theoretical perspective the misunderstanding arises because of the widespread view that Consumption can lead growth. Therefore, it is argued, the Government should increase its own Consumption in order to foster recovery. The premise is false.

Consumption cannot lead growth because it is not an input to it. Consumption is a consequence of production, and growing Consumption is a consequence of growing production. If production has not risen increased Consumption requires borrowing, which is a financial claim on future production. Furthermore, if an increasing proportion of output is devoted to Consumption rather than Investment the growth rate of the entire economy will slow, and so too will Consumption.

Yet ‘keynesians’ and other progressives who wish to end austerity persist in arguing for Government to increase Consumption by borrowing on its own account- hence the attacks on McDonnell. This is also flies in the face of economic history.

History

It is widely recognised the economic growth rate of the UK and of many of the Western economies was greater in the post-World War II period, from 1945 to the early 1970s than in the subsequent period. This recognition includes ‘keynesians’ and many others, some describing it as the ‘Golden Age’.

This itself is a misreading as the far higher growth rate in the US and to a lesser extent the UK was in the pre-war and war period itself. The exceptionally strong growth was caused by the state taking control of investment and directing very large increases, in order to wage war. The subsequent ‘Golden Age’ was the gradual deceleration of this war boom.

Even so, the recognition that growth in the post-War period was markedly stronger than the period beginning in the early 1970s is shared. It is factually correct. Yet this ‘Golden Age’ does not at all conform to the ‘keynesian’ prescription for permanent public sector deficits on the current Budget. In fact it shows the opposite.

In Fig.1 below the UK Current Budget Deficit is shown as a proportion of GDP. A level above zero shows a deficit. Below zero shows a surplus. For the entire period of the ‘Golden Age’ the UK Current Budget was not just balanced, it was in surplus.

This post-WWII period of large current Budget surpluses coincided with the establishment of the NHS, the creation of the ‘welfare state’, a massive public sector house building programme, large scale nationalisations and other measures.

How is this possible? How can there both be (sometimes huge) surpluses on the current Budget while Government current spending was initiating a whole series of new or improved public goods?

The answer is investment, public investment. Fig.2 below shows the level of Public Sector Net Investment as a proportion of GDP over the same period.

This explains why both rightist and leftist criticisms are misplaced. The McDonnell framework will not lead to austerity if investment is increased. More importantly, it offers a way out of the crisis. If investment is sufficiently strong the economic recovery will provide sufficient tax revenues and lower social security outlays to become self-sustaining. This improvement in government finances can be used for more investment and for increased current spending.

On the other hand, if it should be the case that recovery remains weak and therefore the current budget remains in deficit, then the answer would not be to cut current spending, but to increase public sector investment.

The period of the greatest advances in public sector current spending took place when there were surpluses on this current account, only made possible by relatively high levels of public investment, in British terms at least. Current spending has been in crisis ever since 1974, with Denis Healey’s fake IMF crisis, then Thatcher and her successors, who slashed public investment.

Mainstream economics largely tries to bury economic history. Those genuinely seeking an alternative to austerity should not make the same mistake.

Recent Comments