.647ZEconomics and the debate on immigration

By Michael Burke

Political parties in Britain have once more begun to talk about immigration, especially in the wake of the Eastleigh by-election. Unfortunately the debate is usually an all-informed one and typically just a cover to introduce racist notions about the impact of immigration. Therefore it is useful to examine some of the more important economic aspects of immigration.

Immigration

There are a number of countries in the world which have a higher per capita GDP than Britain. There are also a number of countries in the world who have a higher proportion of migrants as a proportion of the population. Both those facts are worth stating simply because discussion in Britain often seems to be dominated by the implicit assumption that Britain is both uniquely attractive to migrants and that it alone experiences immigration.

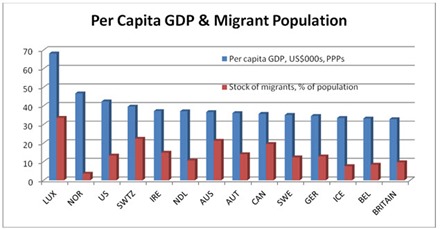

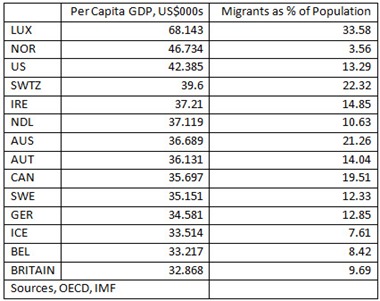

The chart below shows the countries with higher levels of per capita incomes than Britain. It also shows those countries proportion of the population which is migrant, that is not born in the host country. The table below specifies the data shown in the chart.

Chart 1

Table 1

There are 13 countries in the world with a higher per capita income than Britain. Of these, 10 countries have a higher proportion of migrants. Some of these, such as Australia, Switzerland and Luxembourg have very much higher levels of immigration and have a much higher level of incomes.

There are 3 countries which have higher incomes but lower levels of immigration. However, of these 2 countries, Norway and Iceland have higher per capita GDP because they have a very large energy resource that comes pumping out of the ground (oil and geothermal energy). The remaining country is Belgium, whose geographic position means it has an exceptionally high proportion of people who work in Belgium but commute there from other countries.

By contrast, among the 18 OECD countries with a lower per capita income than Britain 12 also have a lower proportion of the population as migrants. The remaining 6 countries are small economies which generally have specific geographic or historical reasons for unusually high levels of immigration, or both. (The exception in this group is France).

Migration is part of growth

According to the IMF the total number of migrants in the world rose from 75 million people in 1965 to 195 million in 2005. Official data shows that most of that is to high income countries, about 80 million and most of the remainder to middle income countries.

The growth in the world’s migrant population is far more rapid than the growth in the total population. Over the same 40-year period to 2005, the world population doubled while the migrant population grew by 3 times.

However, this cross-border migration captures only a fraction of the world’s total migrant population. From a strict economic perspective there is little difference between cross-border migration and internal migration. This is especially the case when internal migration encompasses vast distances and differences of language or dialect.

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics in 2008 there were 285 million internal migrants in China. This is far larger than the world’s total number of cross-border migrants. For the migrants themselves this frequently encompasses far greater geographical distances than is required, say, in intra-Western European migration. This level of migration is certainly the greatest level of internal migration in human history. It is also associated with the greatest rate of growth for any major economy in world history.

In India the level of internal migration is over 300 million people according to UNESCO. India’s medium-term growth rate is below that of China, but both countries have been growing at a rate considerably faster than the high income countries. The rate of internal migration has been a necessary accompaniment to high growth rates.

Correlation does not prove causality. But within the high-income countries higher levels of income are associated with higher levels of migration. Within the middle income countries, higher growth rates are associated with higher levels of internal migration.

Economic development depends on two key factors, the proportion of national income devoted to investment and increasing participation in the division of labour. Migration is a key part of the division of labour, allowing workers to migrate where production (and wages and jobs) are expanding. It also allows production to increase on the basis of employing the most adaptable workers.

Opposition to immigration

The government has recently produced a video to show potential migrants from Romania and Bulgaria that Britain is not a great country to emigrate to. There is a certain logic to this. The only way to stop immigration over the medium-term is to reduce the growth rate of the economy to zero or below. This is the basis for the government’s self-proclaimed success in reducing net migration in the most recent data; by curbing overseas students growth is directly reduced. Of course prolonged economic stagnation would also lead to a more rapid swelling of the 5 million British people who now live overseas.

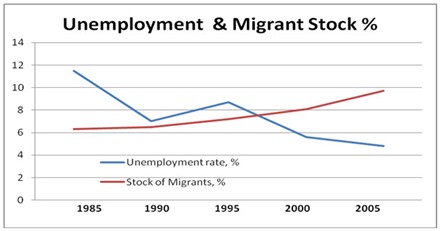

Immigration of all types provides a substantial net benefit to the British economy, which a Home Office report clearly demonstrates. Growth attracts immigration but is also increased by it. The proportion of workers leaving a country will increases when there is an economic downturn and the proportion of the workforce arriving from overseas will tend to decrease. The reverse is also true: net immigration increases when the economy prospers.

There are a series of reactionary myths about immigration, which are perpetuated in the labour movement by outfits such as ‘Blue Labour’. These tend to focus on the supposedly local or microeconomic effects of immigration, particularly that they drive down wages. These arguments are a rehash of Labour notions which opposed the growth of women in the workforce and even supported restricting their wages relative to men.

Jonathan Portes has done very good work in countering the assertions that immigration drives down wages, even for the very lowest paid workers in Britain. As the Home Office study shows, the average wages for migrant workers in Britain are also about 5% higher than British workers, because on average they are more highly qualified. The relationship between unemployment and immigration is also equally clear; immigration increases while unemployment falls and vice versa.

Chart 2

In reality the debate on immigration in Britain is not about the economic causes and consequences of immigration at all. It is overwhelmingly a ‘debate’ that allows politicians and others to whip up xenophobia and racism, while posing as being concerned about the interests of workers or the poor. The cause of migration is growth, to which migration is a decisive contributor. The consequence is stronger growth. The contrary argument is being raised now as a reactionary diversion from the current economic crisis, and the policies which are responsible for it.

Recent Comments