By Michael Burke

The advanced industrialised economies have gone from being in a low-inflation or even deflationary environment to an inflationary one, seemingly in the blink of an eye. The situation is even worse in the developing economies, with shortages of basic foods and energy as well high prices.

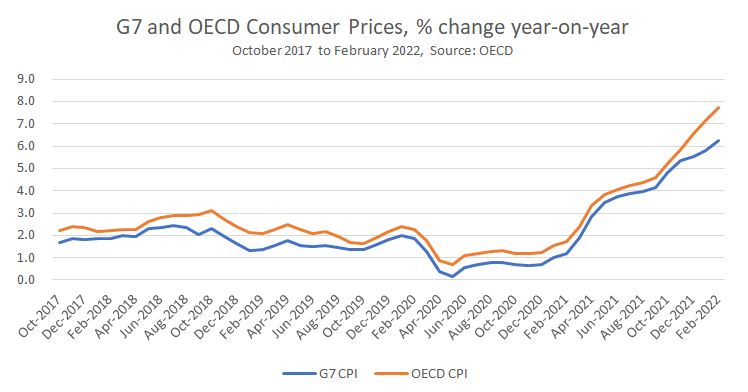

There has been an entire cottage industry among economists over the past period discussing the causes, consequences and remedies for deflation. No longer. That period ended at the beginning of 2021, as Chart 1 below shows. Because the inflationary process has already been subject to a degree of mythologising, it is necessary to set out the factual mechanics of the process in a little detail.

Chart 1. Consumer price inflation in the G7 and OECD

Until the end of 2019 and for many years preceding average consumer price inflation in the G7 tended to vary between 2% and 3%, sometimes even lower. However, the pandemic which ripped through the world, and whose effects were especially prevalent among the G7 and OECD economies, as well as the lockdowns it caused, pushed both economic activity and prices lower. CPI inflation pushed down towards zero.

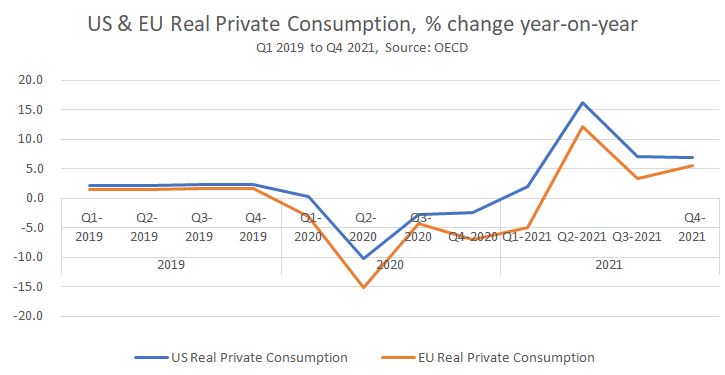

That deflationary episode then ended dramatically at the beginning of 2021 and until the most recent data in February 2022. The cause of the sudden change was the ending of lockdown in these economies and the sharp rise in economic activity that ending lockdown caused. This surge in Consumption in two of the leading advanced economies is shown in Chart 2 below.

Chart 2.Change in Real Private Consumption in EU and US, 2019 to 2021

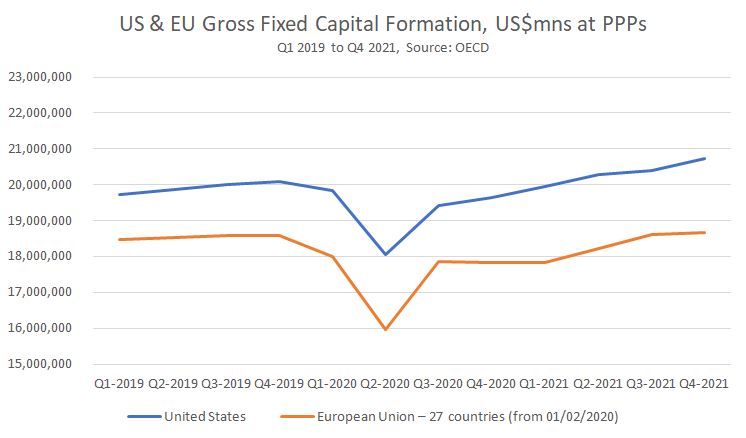

However, there was no corresponding increase in Investment in these same economies over the same period, as shown in Chart 3 below.

Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) in the US and in the EU was barely higher at the end of 2021 than it had been at the beginning of 2019. If we take the two-year period as a whole, given the deep slump in Investment in the 2nd quarter of 2020 as lockdowns took effect, the average level of Investment was lower than prior to the pandemic.

Chart 3. US and EU GFCF in the pandemic

In common usage, there was an increase in demand but no increase in supply. More accurately, there was an increase in Consumption without an increase in Investment. In classical economic theory this leads to rising prices. As noted at the beginning of this piece, that is precisely what happened from the beginning of 2021 onwards.

The other main explanations for the rise inflation are not at all rooted in facts. The suggestion that this round of inflation was brought on by the conflict in Ukraine can be dismissed as the conflict only began in late February this year. However, it is certain that since both Russia and Ukraine are globally important producers of key commodities, there will be very large and serious inflationary consequences that arise for hundreds of millions of people as a result. But these effects are only beginning now and will be touched on further below.

The earlier claim that it is China that is to blame is less easily dismissed, but only marginally so. The disruption to the Chinese economy arising from the pandemic has clearly been less severe than in the G7 or in the OECD economies, as evidenced by its relative GDP growth rate over 2020 to 2023. For example, IMF projections for real GDP growth over those 3 years is over 16% for China, which is more than double that of the US.

But the more subtle and potentially dangerous claim is that it is the Chinese response to the pandemic which has caused the global ‘supply-chain bottlenecks’ which have pushed prices higher. This in turn is used as a demand that China should end its zero covid policy.

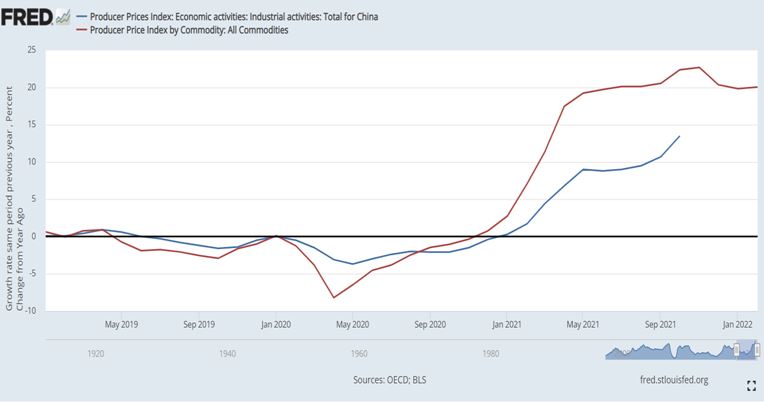

However, it is not factually accurate. The ‘bottlenecks’ have their source in the advanced industrialised countries. So, even though China provides vastly more raw materials and semi-finished goods to the US, EU and other advanced industrial economies (as well as finished goods) than it imports from them, producer prices began to rise in the US slightly before they rose in China. Crucially US producer price inflation is far in excess of Chinese PPI (in October 22.4% versus 13.5%). These producer price inflation rates are shown in Chart 4. Below.

Chart 4. US and China Producer Price Inflation

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve

US producer prices began to turn before those in China, and the rate of inflation in the US much higher. These do not support claims that China is the source of ‘global bottlenecks’.

There is a further point, worth repeating about the consequences of inflation. Naturally, the beneficiaries of inflation are those firms who stand to gain from the rise in prices, the most obvious of which are the Big Oil firms currently. But others will be cashing in too from rising commodities’ prices, including agri-food businesses, Big Pharma, the nuclear industry and others.

However, the severity of the crisis will mean huge hardship for hundreds of millions of people, possibly billions of them. Supplies of essentials may slow to a trickle or even dry up altogether, especially in light of US-led sanctions. Or they may reach prices which force hardship and even hunger for the poorest populations.

According to the UN, 45 African and ‘least developed’ countries import at least a third of their wheat from Russia or Ukraine – 18 of those countries import at least 50 percent. Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer, obtains over 70 percent of its imports from Russia and Ukraine, while Turkey obtains over 80 percent.

In general, in the advanced industrialised countries there will be far greater misery than at present, with millions of people forced into some version of ‘heat or eat’. In the developing world, hundreds of millions will suffer even greater hardship and outright starvation is not ruled out for some. The sanctions regime now in place will hit the world’s poorest, far beyond the arena of the conflict.

The inflation outlook is very grave. The G7’s failure to invest and the co-ordinated ending of lockdowns was the initial cause. Those factors have now been compounded by the war in Ukraine and the sanctions that have followed.

Recent Comments