.387ZAfter Trump’s victory China is the main strategic pillar for globalisationBy John Ross

Trump’s election as US President means 2016 is ending with a stark public contrast between the positions of China and the US on global trade. The US has its first president proclaiming support for protectionism since World War II, while China states its support for increased international trade and economic globalisation.

December 2016 also marks the first anniversary of China’s major free trade agreements (FTAs) with South Korea and Australia – so far China has signed 14 free trade pacts with 22 countries and regions in Asia, Latin America, Oceania, and Europe. In contrast Trump, far from calling for extending FTAs, has called for revision even of the existing North American Free Trade Agreement – the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investors Partnership (TTIP) are different issues as analysed below.

This reality that China is now the largest economy supporting progress towards free trade, while the US moves towards protectionism, is therefore a key event in the world economy. It is consequently crucial to analyse both the fundamental issues involved, that is the most powerful forces driving the process, and the immediate practical consequences for China in pushing for FTAs and to understand the consequences of the contrasting strategic approaches of China and Trump.

The importance of trade

First, analysing the most powerful forces in economic development, international trade is one of the clearest issues where economic theory and the facts of economic development completely coincide. Economic theory states that international trade will aid economic development: numerous and repeated factual studies show a positive correlation between the trade openness of an economy and its speed of economic development. Nevertheless, to understand developments in the world economy given the now contrasting policies of China and Trump it is crucial to understand the reasons for the firmly established positive correlation of trade and the rate of economic development in the modern globalised economy.

Trade and division/socialisation of labour

Trade’s importance does not arise from some ‘magic effect’ of crossing national borders. The distance from Shanghai to Beijing and from Shanghai to Osaka is approximately the same, but the importance of trade does not mean that there is some extra benefit from Shanghai’s trade with Japan rather than another part of China.

International trade’s importance follows from the proven fact of the first sentence of the first chapter of the founding work of modern economics, Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations: ‘The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is directed, or applied, seem to have been the effect of the division of labour.’ Marx used the term ‘socialisation of labour’, rather than ‘division of labour’, but entirely agreed with Smith’s conclusion.

Modern econometrics fully confirmed the Smith/Marx analysis. Modern econometrics finds, in economic ‘growth accounting’ terminology, that the most powerful factor in economic growth is the increase in ‘intermediate products’ – that is the output of one industry (e.g. a steering wheel, a hard drive) used as an input into another industry (e.g. a car, a computer). But the increase in ‘intermediate products’ is merely a measure of increase in division of labour.

Modern econometrics also finds that the second most powerful factor in economic growth is fixed investment. But fixed investment is again simply another form of division/socialisation of labour – the use of the outputs of capital goods industries to produce other products.

The key role of international trade follows directly from this decisive role of division/socialisation of labour. As Smith immediately noted: ‘the division of labour is limited by the extent of the market’ – increasing division/socialisation of labour required an increasing market size. It was for this fundamental economic reason that Smith advocated free trade and Marx was a fierce critic of the founder of modern ‘protectionist’ theory Friedrich List

It is this increasing division/socialisation of labour, not of crossing national borders, that is decisive for economic development and which therefore allows the unfolding economic processes involved with Trump and China’s current policies to be understood.

‘Opening up’

These fundamental economic forces evidently explain the success of China’s ‘reform and opening up’ process since 1978 – and why China seeks new FTAs. A key reason for China’s more rapid economic than other major economies is that it makes greater use of international division of labour than the other two of the world’s three largest economies. China’s trade in goods and services in 2015 was 41.2% of China’s GDP compared to 36.8% in Japan and 28.1% in the US. Given the success of the ‘opening up’ policy it corresponds to China’s national self-interest to press forward with proposals for freer trade and FTAs.

But the fact that this advantage of division/socialisation of labour in economic development is the foundation of trade means equally means that developing this is in the interests of other countries as well as China. The statements that in economics ‘one plus one can be more than two’, and the concept ‘win-win’, are not pleasant but empty words but correspond to this decisive economic advantage of division/socialisation of labour. This is why China has been able to secure its free trade agreements with South Korea, Australia and other countries, and why it wants more.

It is also the beneficial effects of such globalisation that has helped produce rapid economic growth in China, India and other developing countries, thereby helping lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Globalisation is consequently decisively important for countries, but particularly developing countries and the world’s poorest people, to achieve economic development.

US economic history

If China since 1978 dramatically illustrates the advantages of open trade US history provides one of the most dramatic examples of the negative nature of protectionism. The passing of the Smoot–Hawley act raising US tariffs in 1930, against the advice of huge numbers of US economists, was a decisive factor in the depth of the Great Depression. Trade’s share in US GDP dropped from 11.0% in 1929 to 6.6% in 1932 and was still only 7.6% in 1938 on the eve of World War II. US GDP fell by 26% between 1929 and 1933, and was only 2.0% above 1929 levels by 1938.

Following this devastating experience of the Great Depression after World War II the US turned policy through 180 degrees and actively built a globalised world trade order. The US played a decisive role in seven rounds of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) each of which further liberalised world trade. This culminated in 1995 in the creation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Every US President from Truman to Obama declared support for freer trade and many acted on it. It is this 71 year old at least verbal commitment to freer trade that Trump’s campaign broke with.

TPP and TTIP

To fully understand the present stark contrast between China and US positions on global trade it is important to realise that the US already began to break with the goal of an increasingly globalised world economy in reality if not in rhetoric under Obama. The TPP and TTIP differed decisively from previous trade agreements under GATT and in creating the WTOs. Their real content was regionalised protectionism for the US beneath mere words on support of freer trade.

This real content was shown extremely clearly in the TPP. The US and China are the world’s first and second largest trading nations and overwhelmingly the largest Pacific trading nations. The foundation of a genuine US orientation to freer trade in the Pacific would have been to negotiate with China. But instead the US deliberately excluded China from the TPP negotiations – confirming that, as numerous Western analysts noted, the TPP’s real aim was not to liberalise trade but to form a bloc under US dominance against China. As US Secretary of Defence Carter stated: ‘In fact, you may not expect to hear this from a Secretary of Defense, but… passing TPP is as important to me as another aircraft carrier.’

The domestic political problem with the TPP for the US administration, however, was that to enshrine the interests of US corporations it tipped the playing field even further against American workers. As well-known US economist Jeffrey Sachs noted of the TPP’s provisions: ‘Their common denominator is that they enshrine the power of corporate capital above all other parts of society, including… even governments… The system proposed in the TPP is a dangerous… blow to the judicial systems of all the signatory countries.’

As the TPP did nothing to improve the position of the US population, indeed would have worsened it, the TPP became politically toxic. All three candidates with major support during the US presidential election and primaries – Trump, Clinton and Sanders – were therefore forced to declare opposition to the TPP. Huge opposition to the TPP existed in the US because it was an attack not only on China but on the US population.

While Trump has in words turned the US from support for free trade and globalisation to protectionism, Obama had already done it in practice with the TPP and the TTIP.

China as the champion of a globalised economy

Trump famously declared during the presidential election campaign he would put a 45% tariff on Chinese imports in the US and would declare China a currency manipulator on ‘day one’ of his administration. As, however, Trump made several wholly impractical proposals during his campaign, such as that Mexico would pay for a wall along its entire border with the US, what Trump will actually do is not yet clear. As the US Peterson Institute noted: ‘If implemented, these proposals [of Trump] would provoke retaliation by US trading partners, unleashing a trade war that would send the US economy into recession and cost millions of Americans their jobs.’ In particular: ‘Industries that manufacture machinery used to create capital goods in the information technology, aerospace, and engineering sectors, which depend on exports, would be the most intensely affected. But the trade shock would also damage sectors not engaged in trade, such as wholesale and retail distribution, restaurants, and temporary employment agencies, particularly in regions where traded commodities are produced. Millions of American jobs that appear unconnected to international trade—disproportionately lower-skilled and lower-wage jobs—would be at risk.’

Putting a tariff on China’s exports to the US would also raise prices for US consumers and thereby reduce US living standards. By being inflationary such price increases would also increase pressure on the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates creating downward pressure on US economic growth. Undoubtedly the very large size of the US economy, which allows great domestic division of labour, and the fact that even Trump does not propose a return to protectionism on the scale of the 1930s, means that the negative effects of protectionism might develop more slowly in the US than in other well-known examples of the failure of protectionism in a modern globalised economy (pre-1990s India, Argentina etc). Nevertheless, turning its back on the advantages of international division of labour would necessarily lead to a slow path of growth of the US economy, and lower living standards, than if it pursued the path of an open economy.

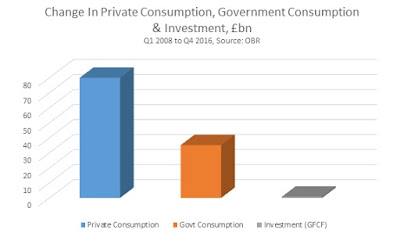

The current problems in the US economy do not stem from its globalisation, on the contrary this has helped prevent any decisive economic decline of the Great Recession type, but of underinvestment in the US economy – a process analysed in detail in my book 一盘大棋?中国新命运解析 (The Great Chess Game?).

The TPP

There is no doubt that one of Trump’s most popular pledges in the election was to oppose the TPP. The problem for Trump is that the majority of US big capital precisely wants a deal like the TPP. Possibly Trump will conclude that anger over his reneging on a pledge to oppose the TPP would be so unpopular it cannot be done openly. But that merely means that Trump will try to secure the same anti-China results as the TPP through other means.

Nevertheless, Trump’s goal is easier to decide upon than to achieve. It took tremendous efforts to get other countries to agree to the TPP. Abe was desperate for the TPP to be adopted – Japan’s parliament ratifying it even after Trump’s election. Difficulties in the TPP therefore create the opportunity for China to promote for a genuine agreement in the Pacific which expands trade rather than the protectionism which was embodied in the TPP.

China has become the main pillar of globalisation

It is the above processes which create the strategic fact that it is China that has now become the world’s largest single economy committed to free trade and globalisation – although the EU is also at least in theory a supporter of this process and the EU’s most powerful economy, Germany, is an enormous beneficiary of globalised trade. The world rapidly growing major economy with China, India, is also sharply increasing its economic openness. The percentage of India’s economy devoted to trade is, at current exchange rates, now even slightly above China’s. The powerful positive effect of foreign trade is once more confirmed by the fact that the world’s five most rapidly growing non-oil dominated economies since the early 1990s with populations of more than five million – in descending order China, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and India – all have high percentages of trade in GDP. Therefore, even if the US moves towards protectionism other rapidly growing economies remain committed to globalisation and China’s decisive task is to place itself decisively among and help lead the process of the rapidly growing economies seeking the advantages of international and globalisation.

China’s policy and RCEP

China’s strategic policy of supporting freer trade and globalisation can be broken down into a series of initiatives which in present circumstances give it key advantages to play a still greater global role – particularly compared to Trump’s approach in the US.

The most important proposal of China is of course to support the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – the proposed FTA between the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) and the six states with which ASEAN has existing FTAs (Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand). RCEP negotiations were formally launched in November 2012 at the ASEAN Summit in Cambodia. China is arguing for them to be concluded as rapidly as possible.

RCEP has numerous advantages over the TPP. In particular, key proposed participants in RCEP are rapidly growing economies (China. India, Vietnam, ASEAN as a whole etc.) whereas the TPP is based on slowly growing economies (Japan, US).

Like China’s existing FTAs RCEP builds on real trading relationships – China takes about one third of Australian exports and over 20% of South Korea’s. With full implementation of the FTA agreement with Australia, for example, 95% of Australian exports to China will be tariff free.

Unlike the TPP and TTIP, which were primarily based on giving international jurisdiction to institutions which would be controlled by a single country (the US), China’s existing FTAs, like RCEP, emphasise harmonisation of national standards with international supervision and interference reduced to an absolutely necessary minimum.

OBOR and AIIB

Finally, China has shown its ‘thought leadership’ on globalisation by initiatives which go beyond the approach of the US in GATT and the WTO. These initiatives were based primarily on tariffs, legal changes, regulation etc. They did not address the actual question of creating the material basis for trade. China’s initiatives in One Belt One Road (OBOR) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) go beyond this by laying the basis for practical development of trade, in particular by infrastructure investment. It is for this reason that even before Trump came to office the AIIB and OBOR were attracting great international attention even from traditional allies of the US such as Britain and Germany.

Conclusion

To summarise, in very important matters, such as Trump becoming US president, it is necessary to be precise and not exaggerate. It remains to be seen how much Trump’s protectionist rhetoric is translated into protectionist practice. Nevertheless, even the change in rhetoric is important. China has now publicly become the world’s largest nation supporting and acting as a pillar of globalisation. As globalisation is the process which has brought immense benefits to the world economy, and particularly to developing countries, this creates key international strategic openings for China.

* * *

This article was previously published here on Key Trends in Globalisation and originally appeared in Chinese on Sina Finance.

Recent Comments