By Tom O’Leary

Bolivians vote in a general election on October 20th. Evo Morales has been the President since 2006, winning three successive terms as President.

A victory for him would continue the development of the economy and the rise in living standards since he took office. It would be a considerable boost to the left across Latin America, which otherwise faces the impositions of Bolsonaro, Macri and Moreno, backed by the US and in some cases the IMF. Socialists internationally have every reason to support a Morales victory.

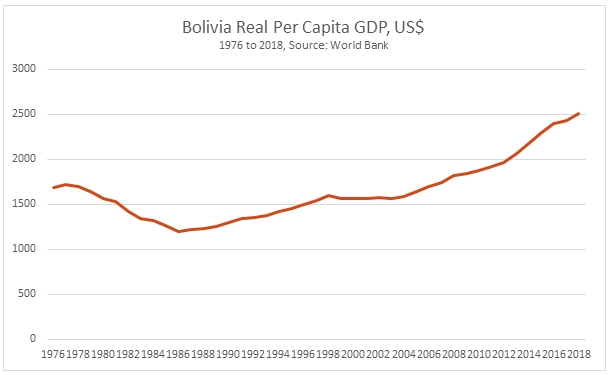

The success of the project begun by Morales and the MAS (Movement for Socialism) can be shown in 2 charts. The first below shows the level of Bolivian real per capita GDP since 1976. In the 30 years before Morales came to power, real GDP per person effectively stagnated. In 1976 it was US$1,687 and was only $1,692 in 2006, barely altered. Since then it has risen to US$2,506, according to World Bank data. This represents a rise in average living standards of 48%.

Fig. 1 Bolivia Real GDP

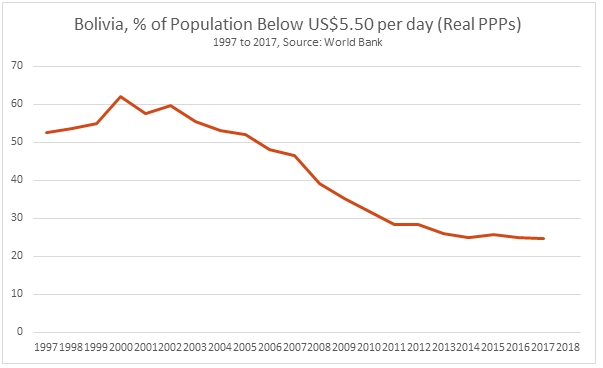

However, it is possible that average living standards rise but that the bulk of this increase is claimed by the rich and the upper classes. But this is not the case in Bolivia. Chart 2 below shows the proportion of the population below the poverty headcount rate of US$5.50 per day, adjusted for inflation and PPPs (purchasing power parities).

Fig.2 Bolivia, % of Population on Incomes Below US$5.50

Once again, this measure of poverty shows there was little progress before Morales. In 1997 52.6% of the population were subsisting on incomes equivalent to below US$5.50 a day in real terms. By 2006 that rate had edged down to 48.1%. But the fall since then has been dramatic, with the poverty rate at 24.7% in 2017 (the latest available data). As the population of the country is now over 11 million, this means that literally millions of people, about one-quarter of the population, have been lifted out of poverty.

The success of Morales

There are a number of factors which have contributed to Morales’ success. Initially, like many countries in Latin America and beyond, Bolivia benefited from the rise in global commodities’ prices, which were spurred on in particular by the rapid pace of China’s industrialisation. There was too a major shift in the population from the countryside to the towns and cities, which rapidly expanded the workforce available for more advanced production, including manufacturing.

But these factors were common to many countries, especially in Latin America, but unlike Morales they failed to maintain their gains, or even to hold onto office. That commodities’ price boom has since faded as the Chinese economic model has adjusted, and the pace of the migration into the urban centres has slowed in many countries. The world economy is also slowing, so none of the previously favourable conditions is likely to return in the foreseeable future.

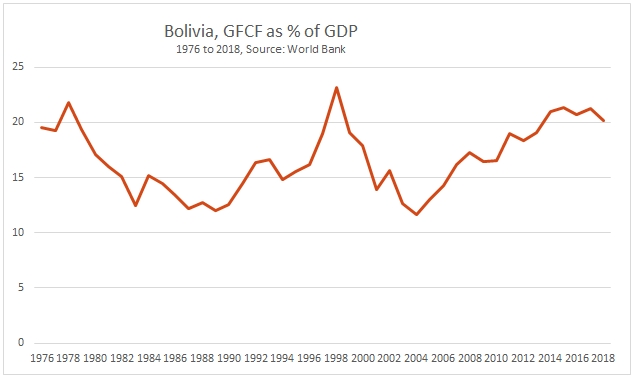

To explain Morales’ success, one key area where the Bolivian economic project stands apart, certainly in Latin America, is that the gains of rising prices and output were not simply used to boost consumption, but also to increase investment. Chart 3 below shows the proportion of GDP directed towards investment, or GFCF (Gross Fixed Capital Formation).

Fig. 3 Bolivia, GFCF as % of GDP

In 2006 GFCF as a proportion of GDP had fallen to a 14.3% and had been even lower in the preceding period. It has since risen to 21.4% in 2015, although it has softened a little in following years. The urban population is now 70% of the total, so there is diminishing scope to increase the workforce available for more advanced manufacturing or industrial production. Further gains will require the return to previous high levels of investment, and even their extension.

Prospects

The validity of opinion polls is hotly disputed, although many show Morales well ahead but short of an outright majority for the first round of voting.

The stakes are very high. The insurrection in Ecuador against enormous price hikes, imposed by the Moreno government acting on the instructions of the US and IMF, shows what the likely alternative to Morales will be. This includes both huge attacks on living standards, and severe state repression to carry it out.

Morales’ political background is as organiser and then general secretary of the peasant farmers, which experienced fierce repression from the large landowners and the state forces, and forced the farmers into guerrilla warfare, Morales included. This is a political formation which creates an understanding of the role of the state, which classes it defends and the brutality of it attacks, all supported by the Unites States. It also teaches the need for collective discussion, unity of action and strong discipline among the resistance fighters. It is clear too that, through this experience and his own ethnic identity, Morales enacts a highly advanced policy towards the indigenous populations.

Despite or because of all this, here in the West there is a campaign of slander against Morales, led by the ‘liberal’ press. So, the Guardian repeatedly runs entirely distorted arguments and outright lies, including describing Morales as ‘the murderer of Nature’ in the Amazon.’ The reality is that it is the far right poster boy Bolsonaro in Brazil, an ally of Trump’s who is destroying the Amazon, and Morales is using every mechanism to combat it.

The stakes are also high for the planet as a whole. The Bolivian elections will not decide that fate, but they are an important battle in the struggle.

Recent Comments