By Michael Burke

The inflationary surge is global. It is causing severe hardship in the advanced capitalist economies and economic disaster, social and political turmoil in large parts of the Global South. Reversing this crisis requires both identifying its source and adopting policies directed at that source.

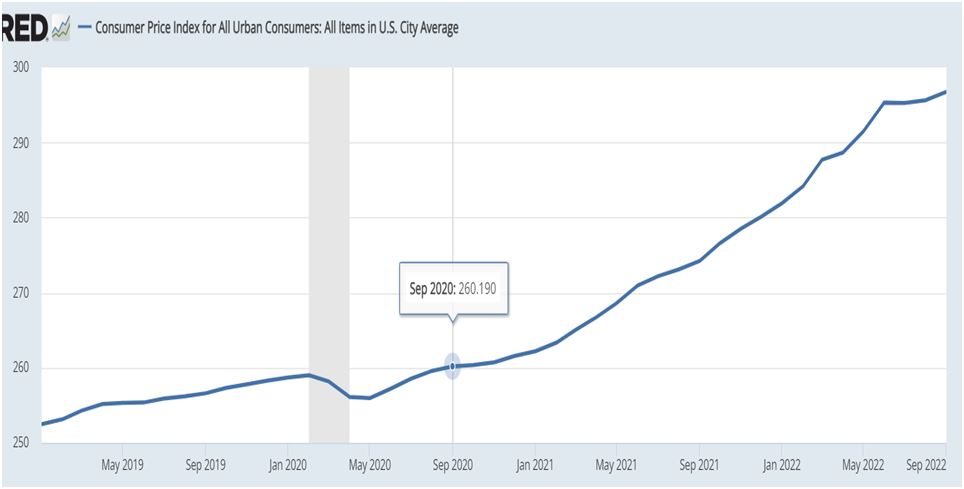

Previously SEB has shown that the widespread claim that the inflation crisis is caused by the war in Ukraine, or, as the Biden administration puts it ‘Putin’s price rises’, is completely false. This is easily shown in the chart below. Far from being a response to the war, US inflation began to rise in May 2020, which is almost two years before the war began (February 24, 2022). No event can cause changes before it even happens.

Chart 1. US CPI inflation index, January 2019 to September 2022

Source; Federal Reserve database (FRED)

Over that period of rising inflation, the cumulative rise in the CPI index has been 16%. Three-quarters of the entire rise in US CPI took place before the war began. Even if we assume that that the entirety of remaining rise was entirely caused by the war (which is not a reasonable assumption), then it is still case that the vast bulk of the rise in prices took place before the war.

SEB has also previously shown that the cause of the inflationary surge was the extraordinary and unprecedented expansion of both US Government Consumption and US money supply. As this followed a prolonged period of weak growth in Investment these policies meant a huge stimulus to the economy when there was no capacity to supply an increase of goods and services. The result was first US, then global inflation.

Money creation

There is one argument that should be addressed, not because it is powerful but because it is both widely shared and completely wrong. This is the claim that ‘poor people don’t have too much money, so the cause of inflation cannot be too much money’. This tends to be put forward by various supporters of the idea that money creation is a panacea, and that production is not central to the economy or the well-being of the population.

It was exactly this type of nonsensical think that drove the Biden administration, among other things, to sending cheques to the population to help out with rent, which had the effect of pushing up rents in the US. Rent controls combined with homebuilding are the appropriate response.

Fundamentally, money creation of this type ignores the existence of social classes and the enormous body of research ever since the GFC and the bank bailout, that relying solely on money creation benefits only the rich and the owners of capital (including landlords). It is perfectly true the poor have no money, but vast money creation makes them poorer still as the owners of capital push up prices.

No surprise of persistently high inflation

In recent months financial markets have repeatedly been thrown off guard by persistently high US inflation. This has led to both a rising US Dollar and rising intertest rates.

Both of these market responses have negative consequences for the rest of the world. A stronger Dollar leads to further upward pressures on inflation as most global commodities remain priced in US Dollars. In addition, global costs of borrowing tend to rise at least as fast as US market interest rates. Here the dominant role of the Dollar is also decisive as the US effectively sets the floor for global interest rates. (Other countries can and frequently can do have lower long-term interest rates, but their currencies play nothing the same weight in global lending).

Financial markets should not have been surprised by inflation remaining high. SEB has previously shown that the causes of inflation are the unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus that has been adopted in the US. Those factors have not significantly abated and as a consequence they remain a force pushing prices higher.

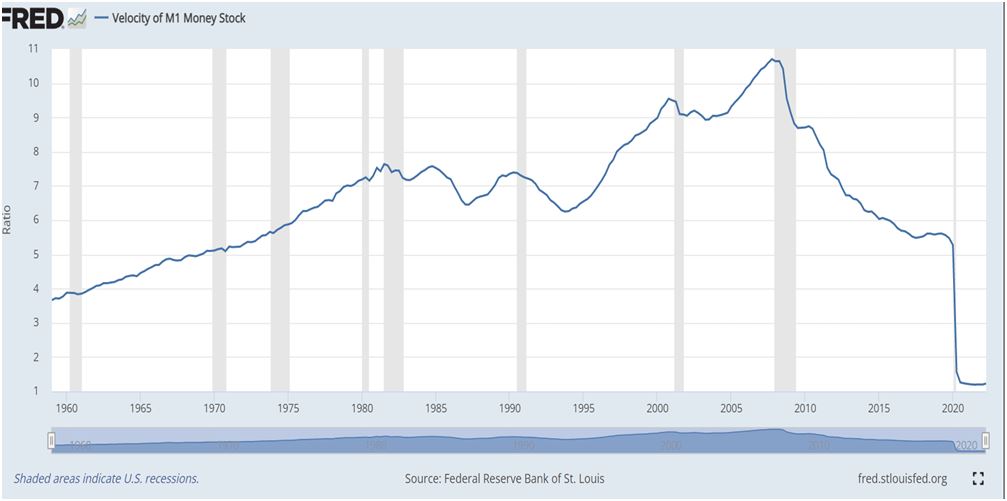

This is shown in the chart below. The velocity of money is a measure used mainly by monetarists, but also others. It is simply the level of money GDP divided by the level of M1 money supply. To return the ratio to its previous lowest ever level would require money supply to be cut by two-thirds from current levels. To return to the previous high-point (and there has been a long-term growth trend in the velocity of money ratio) would require current M1 money supply levels to be cut to less than one-eighth of its current level.

Similarly, while US Government Consumption is not rising as fast as in 2020/21, there is no reduction and may not be, even after the US mid-term elections. Both monetary policy and US Government Consumption remain highly inflationary.

Chart 2. US Velocity of M1 money supply, Q1 1959 to Q2 2022

Source; FRED

Transmission to other countries

As noted above, the global dominance of the US Dollar means that US economic and financial conditions are transmitted to the rest of world. This takes place through a number of related mechanisms; dominance of the US Dollar in global commodities’ prices, setting a floor on global market interest rates and direct currency effects in the exchange rate with the US Dollar.

Even extreme changes in the US are magnified for most countries, but especially for those dependent on overseas capital or who suffer under unequal terms of trade. The countries most badly affected by gyrations in the US economy and financial markets therefore tend to be grouped in the Global South.

International forecasters such as the IMF, World Bank and others have been slashing growth forecasts for world economy including the Global South. In addition, inflation is expected to be rampant in many countries, with double-digit inflation not just last year but forecasts of similar over several years to come. Argentina is one of the worst, with CPI inflation of close to 50% expected for many years to come, close to the hyper-inflation that destroys all fixed incomes and savings.

In the advanced industrialised economies the outlook is not as grim. But Britain is now among those where CPI inflation is above 10%, as is the Euro Area as a whole.

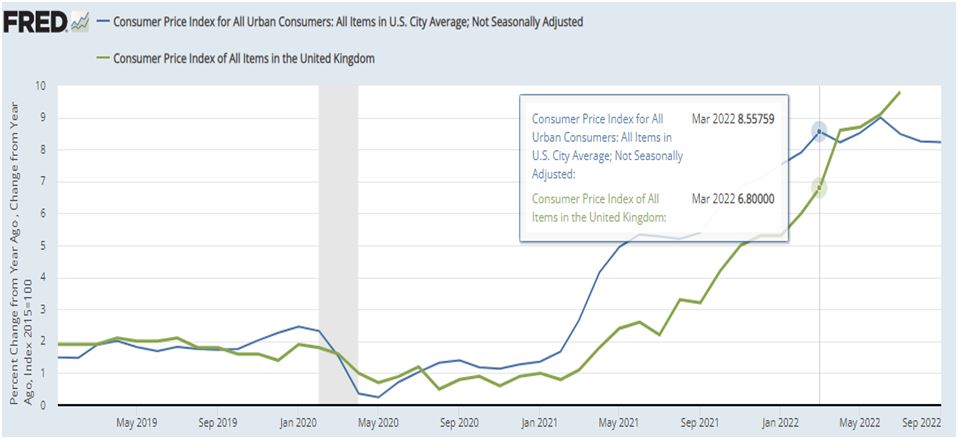

The correlation between US and British inflationary pressures is shown in the chart below. There is a comparable pattern with inflation in the Euro Area. Measured in terms of year-on-year inflation, US CPI began to rise in late 2020. Britain followed a few months later. But British price rises did not exceed those of the US until after the Ukraine war began.

This confirms that the inflationary pressure emerged in the US, especially as the Euro Area price rise is in lock-step with Britain’s. It also completely undermines any idea that inflationary pressures emerged as a result of ‘Chinese supply bottlenecks’ as China itself has experienced no similar rise in prices at all.

Chart 3. US and UK CPI inflation from 2019 onwards

Source: FRED

Almost exactly half the British (and European) rise in prices cannot at all be attributed to the war or its indirect consequences, as they took place before the war began. It is not possible to accurately disentangle the sources of price pressures after that date, but is certainly some combination of US economic policy and the price rises as a result of the war.

But even these are indirect consequences, as it not the case that Russia has cut off Western European countries from energy supplies. Instead, it is those countries that have imposed sanctions on Russia, including a boycott of its energy output.

Reversing the inflation trend

For the world as a whole the two key measures which would see a rapid decline in inflation would be:

- A reversal of the US mix of fiscal and monetary policy that created the inflationary impulse

- The ending of war-related sanctions.

Naturally, for policymakers in the US there are other priorities. These may have included a misconceived attempt to kickstart the US economy to vault over its rivals, the political impossibility of withdrawing massive stimulus before the mid-terms and the war.

For European and other governments who cannot determine US policy the biggest single contribution they could make to suppressing inflation would be to abandon the sanctions regime. This would also benefit countries from the Global South who suffer not only energy price rises but also grain and fertiliser shortages as part of the sanctions regime.

In addition, they could take specific measures to curb energy prices by windfall taxes or legislation to curb profiteering. Some European countries have taken these measures, such as France.

There should also be significantly increased investment in renewables as well as market measures to ensure that their actual price advantage over fossil fuels, gas in particular, is allowed to operate. There must be no more tying of renewable energy prices to gas prices, to subsidise the gas producers.

Structurally, the inflation burst is a reflection of the long-run decline in Investment in the advanced capitalist economies. The US authorities gave a huge boost to Consumption, but without Investment there was no capacity to meet it. The policy of the central banks is now a disastrous one of pushing down Consumption growth to the low level of Investment; causing a slump to lower inflation.

The logical and far less damaging course is to increase Investment and raise capacity. Done in a timely way this would lead to lower inflation and avoid or at least curtail a slump. The starting point should be the needed investment in renewables plus energy saving and insulation, as well as switching to extensive networks of environmental public transport and public housing.

The current crisis was made by policy choices, and it can be unmade by better ones.

Recent Comments