By Tom O’Donnell

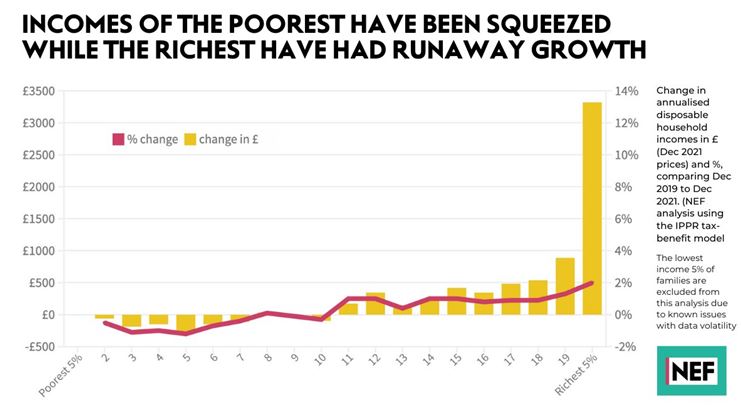

The latest report from the New Economics Foundation (NEF) has done a great service by helping to expose the myth that austerity has gone away under the current government. Instead, they show that incomes for the bottom half of earners have fallen over the last two years while those at the upper end have soared.

This is precisely the definition of austerity, which is the transfer of income and assets from poor to rich and from labour to capital. The key NEF chart is shown below.

Chart 1. NEF chart on the redistribution of incomes from 2019

Of course, Boris Johnson and his government claim they have ended austerity. Bizarrely, this is frequently repeated even among progressive commentators, along with the false claim that wages are rising (in reality pay settlements are running close to 2%, while RPI inflation is 6%, causing a deep cut in real wages).

The aim of austerity

The purpose of the austerity policy is an attempt to address the crisis of British capitalism by lowering wages, increasing hours at lower or no pay, cutting pensions (deferred wages) and other methods of increasing the rate of exploitation.

If firms can increase the rate of exploitation, they may be able to increase the mass and rate of profits. This would then allow them to increase the rate of investment once more, at a new, higher level of profitability.

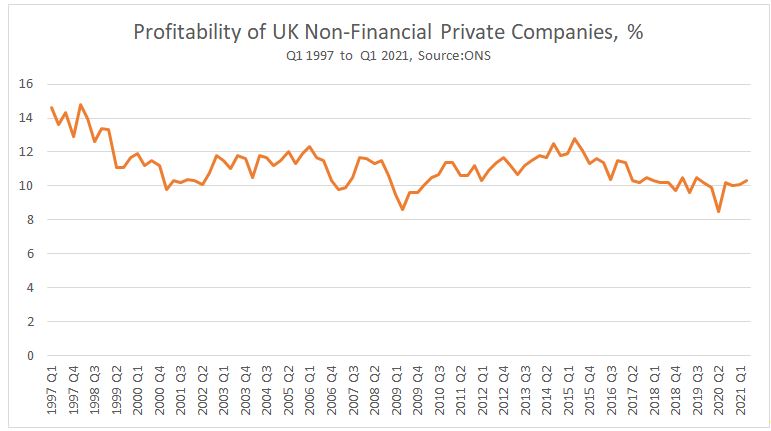

The reason that the policy has been in place for 12 years now is because it has not worked. Chart 2 below shows the ‘profitability’ (the net return on capital employed, in percentage terms) for UK private non-financial firms.

Chart 2. Profitability of UK non-financial private companies, in percentage terms

The return on capital had been falling over a prolonged period and took a sharp lurch lower in the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008/09. It was then that austerity was imposed in 2010 in order to revive profitability. However, this was only partially successful, as profitability peaked in mid-2015 and has been in a downtrend ever since.

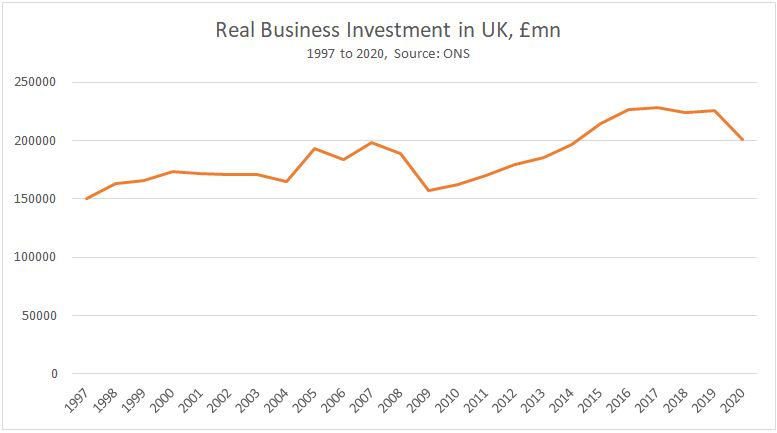

This limited success in reviving profits has had the effect of producing only a partial increase in the rate of business investment, shown in Chart 3 below. This is crucial, as the motor force of the capitalist system is the expansion of capital, driven by the increase in profits.

While gross business investment did increase from the depths of the GFC, it has not sustained that increase and peaked in 2017. That is not long after the peak in profits in mid2017 already noted. Weak business investment does not suggest a robust recovery in profits.

Chart 3

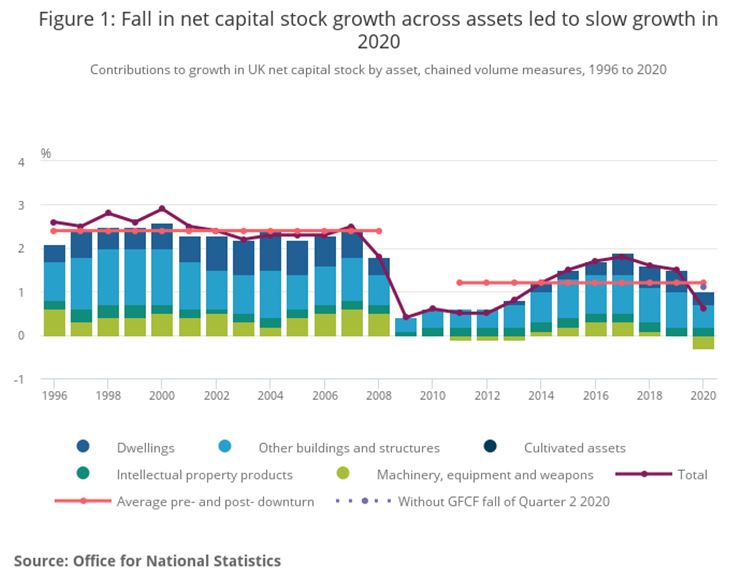

And even these data, based on gross business investment levels do not provide a full picture, because depreciation and dilapidation must be taken into account. This is a measure of the net level of investment, after depreciation and dilapidation and in country such as Britain, is overwhelmingly the domain of the private sector.

The capital stock is increased by investment and reduced by depreciation and dilapidation. The combined effect of both gives the change in the net capital stock. The outcome of the net level of investment is shown in Chart 4 below, reproduced from the ONS.

The ONS chart below shows the key components of the changes in the net capital stock. It also shows two redlines, which are the average growth in the next capital stock before and after the GFC. The first red line shows the average growth in the capital stock at just 2.4% in the years prior to the GFC. But this has since halved to growth of just 1.2% annually.

This is a clear indicator that profits have not recovered to the point where firms feel compelled to increase investment in order to expand capital further or faster.

Chart 4. Net Capital Stock Growth in the UK, 1996 to 2020

Even more austerity

The NEF analysis shows a fall in living standards for the lowest paid half of the population, and a big increase in incomes for the top 5% of earners. This is in line with analysis from both the Resolution Foundation and the Office for Budget Responsibility, republished by the Treasury.

On this evidence, the point that austerity has never gone away is irrefutable. The government clearly has an interest in misleading the population on this point.

Progressive commentators and others who repeat it tend to confuse the total level of government spending with austerity policies. But if lower paid incomes are being hit while the government lavishes the private sector with useless track and trace systems, or useless PPE, to take just two examples, it does not mean that austerity has been reversed.

At the same time, it is quite naïve to believe that a government committed to acting in business interests (to the point of outright corruption in the current case) would willingly abandon austerity anything more than temporarily, for electoral reasons.

Austerity is the central mechanism to restore profitability and so produce a private sector-driven investment recovery. As we have seen, we are still very far from that goal, and so the supporters of austerity will continue on this path until they have achieved their aim, or unless they are forced from it.

Recent Comments