.232ZBritish economic crisis is deepeningBy Tom O’Leary

2017 has begun with some upbeat economic survey evidence although the majority of economic forecasters are cautious about whether this will be sustained. Leading stock market are also at or close to all-time highs. The reality is that the UK economic outlook is deteriorating. This will have both important economic and political effects over the course of the year.

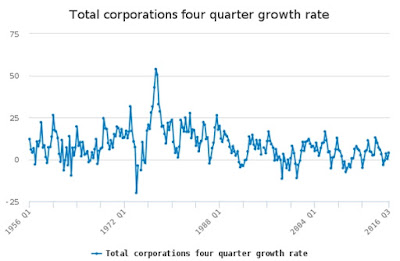

Chart 1 below shows the nominal growth rate of profits for UK companies, quarter-on-quarter. Profits (more accurately the gross operating surplus) of firms have fallen marginally before inflation is taken into account. Once the effect of price rises is included, the fall in profits becomes more substantial.

This is exactly what has happened in the recent period. Firms have stopped investing, and are generally content to hire workers only as an alternative to capital investment or where they can enforce limited hours, low pay, zero hours or other increases in exploitation. In each of the first 3 quarters of 2016 the total level of business investment was below the equivalent period in 2015. In the quarter to October there was no growth in employment, while full-time employment fell by 50,000, made up by a similar rise in part-time work.

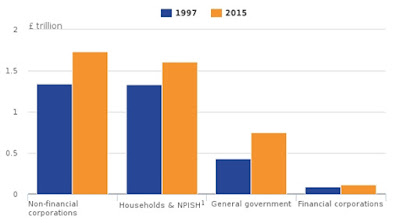

These trends represent the acceleration of longer-term tendencies in the UK economy. Chart 3 below shows the contribution of the different sectors of the UK economy to the total accumulation of the capital stock. From 1997 to 2015 UK companies increased their net capital stock by less than 1.5% per annum.

But this long-term trend has become more pronounced since the crisis. Private companies’ net capital stock has risen by little more than 1% on average per year since 2007. This profit-induced weakness of business investment is the primary cause of the Great Stagnation in the UK and in other advanced industrialised economies since the crisis.

Brexit effect

Since the Brexit vote profits have declined outright and so has business investment. Manufacturing has declined by 1% since June and industrial production has fallen by 2%. The trade gap has widened by £8 billion compared to the same period in 2015, an increase of almost 20%. The forecasts of sunny uplands by the Brexiteers are purely delusional.

There are many single markets in the world. The British economy is itself one, with minor exceptions there are common laws, freedom of movement for goods, capital firms and people, and a unitary currency and fiscal policy. The benefit of the EU Single Market in the making is that it is one of the world’s three largest single markets, alongside China and the US. This provides a powerful magnet for capital seeking profits.

Of course it is possible for small amounts of capital to make very large profits investing in a small market, such as the UK would become with Brexit. But it is impossible for a large mass of capital to make large returns in a small market. And Britain needs large capital inflows simply in order to finance its external deficits.

British firms are struggling to realise profits. Ever since the crisis their level of investment has been abysmally low. This deepened the long-run negative trends in the UK economy. These have become sharply worse since the June 23 referendum. In any Brexit scenario, the less the access to the EU Single Market, the lower the attractiveness of the UK to international capital. Without a dramatic change in Brexit policy, there is little reason for optimism about UK economic prospects in 2017.

Recent Comments