By Michael Burke

The manufactured furore surrounding John McDonnell in the wake of the Budget has a clear purpose. It is designed to distract attention from probably the grimmest set of forecasts delivered in a Budget in the modern era and to deflect criticism from the Tory government.

This is not solely an anti-Labour, pro-Tory propaganda campaign. Contrary to widespread assertions, austerity is not coming to an end and is being deepened. Seven years of falling living standards are not over. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), very far from being a left-wing thinktank, says that living standards will be lower in 2023 than they were in 2008.

This is a doubling down on the failed policy of austerity. It is therefore important for all supporters of austerity to shift attention from the repetition of a policy that has already failed.

Borrowing to invest

The immediate focus of the criticism of Labour plans was the absence of a specified level of interest of government debt arising from Labour’s borrowing. This is perhaps one of the weakest grounds to attack.

This is because Labour’s Fiscal Responsibility Framework is committed to borrowing solely for investment, and balancing current or day-to-day spending on items such as health and education with current revenues which is mainly taxation.

As a result, all of Labour’s borrowing would have a return. The combined effect of borrowing at low interest rates and investing with much higher rates of return is a net boost government finances, which can be used to increase Investment further. The level of government deficits and debt will fall automatically as taxation revenues grow along with increased economic activity.

Currently, government borrowing over any time period (or debt ‘maturities’ in the jargon) costs less than 2%. This is below the level of inflation, which alone means that the borrowing makes sense. Yet, at the same, the returns to commercial investment are on average around 12%. Any government, or business, which can borrow at such low interest rates for such high investment returns would be foolish to pass up this opportunity. It is reckless and extreme that the Tories have passed up this opportunity.

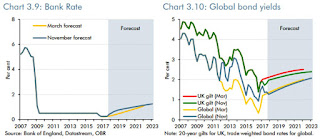

Of course, no-one can possibly know what the level of interest rates will be in a few years’ time. But the official forecasts from the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) suggest only a minimal increase on government borrowing costs (the yields on UK government bonds, or ‘gilts’) over the medium-term.

This is shown in Chart 1 below, with the green line in Chart 3.10 representing the latest forecasts of long-term borrowing costs. These barely move above 2% over the medium-term.

In financial markets there is a calculation used to highlight where interest rates are expected to be in a given number of years’ time. Currently, using this calculation of the difference between 10year gilt yields and 20year gilt yields implies a market expectation that in 10 years’ time, 10year interest rates will be 2.3%. None of these forecasts can be relied on for pinpoint accuracy. Instead, they are shown to illustrate the point that it is reasonable to assume that government borrowing costs remain subdued for some time to come.

Rates and growth

The fundamental point is that when economies grow strong and especially when there is a risk of inflation, all long-term interest rates tend to rise. If the economy is performing strongly, then the pressure on Labour to borrow for investment when it comes to office subsides to some extent. But that is not what any serious commentator, the OBR, IFS or Resolution Foundation thinks is likely.

Instead, government interest rates fell sharply in response to the grim Budget outlook. This should be read as a ‘market signal’ that borrowing for investment should increase. Bond markets could absorb a lot more borrowing before gilt yields were pushed back up even to their very low pre-Budget levels.

The commitment of the Fiscal Responsibility Framework means it is easy to gauge whether the borrowing is sustainable. The decisive criteria is whether the return on the borrowing exceeds the cost of borrowing. As noted above, the average commercial return on investment in the UK is around 12%, a large multiple of the current cost of borrowing. Only if the cost of borrowing rose above that level would it become unsustainable. This seems unlikely in the foreseeable future.

In reality, the net returns to government from the same investment as the private sector are actually significantly higher. To take a clear example, a private developer who builds homes might get a return of 10-12%. But the same returns are available to government for the same project, while the cost are lower. This is because in the course of construction, income tax and National Insurance is paid by builders and other workers (and there is a return on their consumption too via VAT). This is a return to government which is simply not available to the private sector.

So, John McDonnell is right, and his critics are wrong. Borrowing for investment not only makes sense, it more than pays for itself.

Recent Comments