.534ZNavigating a way out of the crisisBy Tom O’Leary

The UK economy is in such a parlous state that the Bank of England is threatening to raise interest rates even though last year’s GDP growth rate was a feeble 1.8% and real wages continue to decline. This is a striking effect of the dearth of investment since the Great Recession.

The Bank’s Governor Mark Carney is concerned about capacity constraints in the economy leading to inflation. This lack of capacity, the weak growth in the means of production, arises because there has been a woeful lack of productive investment from before the recession began in 2008.

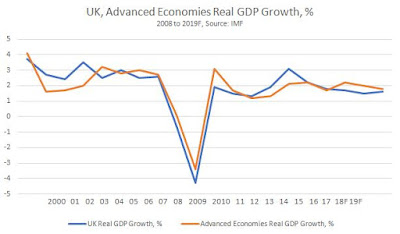

The UK economy is actually receiving a lift from the upturn in the world economy, particularly in Europe, but its relative position is declining. In effect, as the world economy is expected to see its best growth rate since 2010, the UK economy is expected to see its worst growth rate since that time.

In the three years from 2017 to 2019, the latest projections from the IMF are that the world economy will accelerate to an average of just over 3.8% real GDP growth. At the same time the UK economy will decelerate to less than half that growth rate, to just under 1.6%. By contrast, the advanced economies as a whole are expected to accelerate to just under 2.3%. The IMF expects that the main driver of world growth will come from what it describes as ‘Emerging market and developing economies’ at just under 4.9% growth, led by India and China.

The IMF has no crystal ball, and frequently makes incorrect forecasts. But the divergence in growth expectations for the UK economy compared with most of the rest of the world is striking. The UK is also one of only two economies it highlights where the IMF has downgraded its growth expectations.

The UK economy is already in poor shape. The advanced economies have been crawling along in growth terms since the crisis began. Using IMF projections for the next two years, these advanced economies will have grown cumulatively by just 17.1% over 12 years. But the UK economy will have grown even more slowly, by just 14.3%. The relative growth rates for the UK and for the advanced economies as a whole are shown in Chart 1 below.

Austerity and the deficit

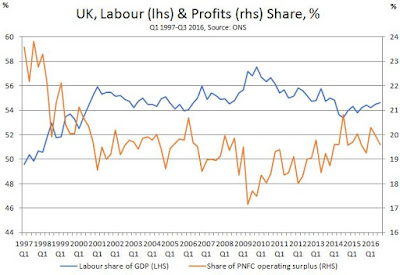

Even the UK’s sub-standard growth rate does not provide an accurate picture of the bleak outlook for living standards. In addition to the sharp deterioration in public services and social welfare provisions, the labour share of national income has fallen sharply since the imposition of austerity in 2010, as shown in Chart 2 below.

Austerity can be seen as an attempt to drive up the profit share from its low-point of 17.1% in mid-2009, just after the crisis began. The prolonged effort has only been partially successful, as the profit share has increased from its low-point, yet it remains far below its pre-crisis highs at the turn of this century.

But the labour share (in an economy that is barely crawling along) has not recovered from its end-2009 peak. Mathematically, the labour share is an independent variable, not determined by the growth rate of GDP and instead determined by the struggle between workers and bosses over wages, pensions and other entitlements. In reality, the struggle for higher or even constant wages is exceptionally difficult when the economy is not expanding more rapidly.

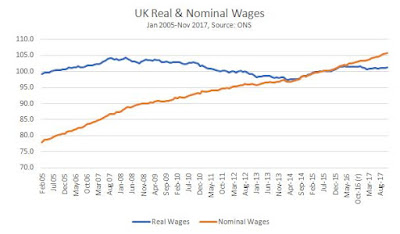

Real wages are now 3% below their peak level in March 2008, as shown in Chart 3. Nominal wages rose 19.5% over the same period, but the two currency devaluations of the pound, one arising from the recession and the other following the Brexit vote, have more than eroded that rise in cash terms via inflation.

Higher wages, just like improved public services and social provisions are much easier to achieve with higher economic growth. But the widespread expectation is that UK growth will be slowing over the next period. This has negative consequences for living standards in the broadest sense, including real pay, social welfare and public services. The consequence for government finances will also be worse, as tax revenue growth will be curbed and outlays related to poverty and under-employment will be higher.

Therefore, in order to address the crisis in living standards and wages, and to tackle the glaring problems in areas such as housing, the NHS, social security, public sector pay and so on, radical measures will be required at a time when government finances are once more under pressure.

Even if Carney is proved wrong in his forecasts of the Bank’s own actions, his pronouncements show that the UK economy could become locked in low growth over the very long-term, with every modest upturn met with higher interest rates to choke off the threat of inflation. To be clear, in mainstream economic policy making all types of inflation are allowed, house prices, stocks and bonds, even Bitcoin. But wage inflation is not permissible and it is this ‘threat’ the Bank of England is poised to prevent.

Navigating a way out of the crisis

Since the recession a number of measures have been adopted which have been designed to boost the economy by raising demand (‘Help to Buy’) or by creating money (‘Quantitative Easing’). By themselves, they are unable to sustainably raise the growth rate of an economy which remains in crisis because of weak investment.

The UK economy is experiencing a productivity crisis, which is not a ‘puzzle’ or ‘mystery’ as is widely claimed, but is instead a function of its low rate of investment. The advanced industrialised countries as a whole are also experiencing a productivity crisis, and the UK is simply among the worst because its level of investment is among the worst.

Productivity matters, because without increasing productivity any rise in living standards is dependent on working harder, or longer hours, or labour trying to claim a greater share of national income from capital.

The world’s leading expert on productivity growth is Dale Jorgenson. In ‘Productivity and the World Economy’ (pdf) he writes,

“The contributions of capital and labor inputs have emerged as the predominant sources of economic growth in both advanced and emerging economies. Economic growth depends primarily on investments in human and non-human capital, including investments in both tangible and intangible assets”.

Using the analysis outlined in his work it is possible to identify the impact of ‘investment in human and non-human capital.’

Jorgenson’s research shows that it is the amount of capital and the amount of labour, as well as their quality, that are the decisive factors in growth. This statistical analysis refutes all efforts to portray growth as ‘demand-led’, or ‘aggregate demand-led’, or a function of innovation, or entrepreneurial activity, or other myths.

In Jorgenson’s new book, ‘The World Economy’ (edited with Fukao and Timmer) he argues that one of its major findings is that, “replication rather than innovation is the major source of growth in the world economy. Replication takes place by adding identical production units with no change in technology. Labor input grows through the addition of new members of the labor force with the same education and experience. Capital input expands by providing new production units with the same collection of plant and equipment. Output expands in proportion with no change in productivity.”

Jorgenson also analyses the historical impact of changes in these inputs for total growth in a variety of economies, including lesser economies like the UK. Using these analytical tools, it is possible to outline a projection of growth for the UK economy based on increasing those inputs, capital and labour, in line with the Labour Party’s intention to end austerity and reverse it. In a follow-up piece, that outline will be presented.

Recent Comments