By John Ross

The following article on ‘The New Shape of World Politics – Disorder in the West, Stability in the East’ analyses the reasons for the Trump administration introducing tariffs against China and the background to the recent G7 and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summits. It was originally published in Chinese by Sina Finance Opinion Leaders, therefore some issues specifically affecting China are dealt with in detail. But the most fundamental features analysed regarding the world situation – the consequences of the ‘new mediocre/Great Stagnation’ in the main Western economies, and their geopolitical consequences – of course apply equally to all countries.

* * *

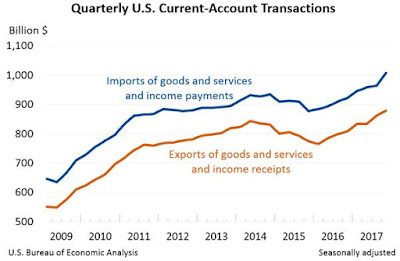

The Trump administration’s imposition of a 25% tariff on $50 billion worth of imports from China [followed now by a threat to impose tariffs on a further $200 billion of imports from China] is an attack on China. But it is simultaneously an attack on the US population – the tariffs will apply downward pressure on US living standards through the increased price of imports and jobs losses due to price increases of components for US production plus the inevitable, already announced, proportionate counter tariffs by China.

The negative effects of such tariffs on the US population can already be seen in the fact that since Trump imposed tariffs on washing machine imports, the average price of laundry equipment including washing machines, has risen by 17% in the US. Price increases for the US population resulting from tariffs against China will, of course, be much widespread and greater than those on a single product such as washing machines.

This US tariff attack on China follows after US imposition of tariffs on steel and aluminium hitting US allies such as the EU, Japan, and Canada. This, and differences on other questions such as sanctions against Iran and the Paris Climate Change Accords, produced sharp disputes at the recent G7 summit in Quebec. The fact that the sharp dispute at the G7 summit took place almost simultaneously with the successful consolidation of the SCO at its own Qingdao summit, with India and Pakistan participating for the first time as full members, showed an increasing trend in world politics – ‘disorder in the West, stability in the East.’

At first sight the Trump administration’s tariffs appear irrational. China, during recent trade negotiations with the US, made reasonable, even generous, proposals to increase US agricultural, energy, manufacturing and other exports to China. China’s trade proposals would have created tens, probably hundreds, of thousands of US jobs and created greater incomes for US farmers. But naturally, China stated that such proposals would be null and void if the US introduced tariffs against China. China’s proposals would, therefore, also have increased the US economic growth rate. Therefore, by proceeding to introduce tariffs, the Trump administration has both foregone the possibility to create many thousands of new jobs in the US, and raise farmers’ incomes – while simultaneously tariffs, by raising prices in the US, will have a net effect of actually losing US jobs.

Nevertheless the US administration’s apparently irrational attacks, not only on China but on the US population and its allies, becomes perfectly comprehensible once it is grasped that the Trump administration in fact cannot significantly accelerate medium/long-term US growth – which, as will be shown, is at present at historically low levels. Therefore, the US form of competition with China cannot be to attempt to substantially accelerate US economic growth, to which no one could object or could prevent, but can only be an attempt to slow down China’s economic development.

The motivation for the apparently irrational actions of the Trump administration therefore becomes entirely clear once the actual factual situation of the US and main Western economies is analysed. The fact that the G7, including the US, is in historic terms is locked in the ‘new mediocre’ also makes clear why there is the strengthening of the trend ‘stability in the East, disorder in the West’.

Disorder in the West

Even before the Trump administration announced its 25% tariff against China the recent outcome of the two almost simultaneous summits involving the most important world leaders, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Qingdao and the G7 in Quebec, was intensely revealing in casting a light on world geopolitics and economics. It would be hard to imagine a more contrasting outcome of two major events.

- The SCO summit saw further strengthening of that organisation, with India and Pakistan participating for the first time as full members. The SCO summit was marked by consolidation of cooperation between SCO countries and in particular by discussions between three extremely large states within it – China, India and Russia.

- The G7, in contrast, was marked by a bitter argument and clashes between the other six members and the US.

It is important for understanding the dynamic of world geopolitics to grasp that this dynamic of ‘stability in the east, disorder in the west’ is not rooted in purely temporary factors. Instead, as this article will factually demonstrate, it is rooted in fundamental features of the global economic situation.

Acrimony at the G7

As the SCO summit was extensively covered in China’s media it is superfluous to give a detailed account here. It is sufficient to note that the expansion of the SCO now means its full members account for over 40% of the world’s population and cover the great majority of the Eurasian land mass. With observer states and dialogue partners the SCO includes 45 per cent of the world’s population. The SCO has, therefore, become the world’s largest regional organisation. The economic driving dynamic of the SCO will be analysed below.

The bitter character of the G7 summit was equally extensively covered in the Chinese media. Nevertheless, to avoid any suggest Chinese media may have exaggerated this, it is worth quoting some of the most authoritative Western news organisations.

- Even before the G7 summit began Reuters reported, under the self-explanatory title ‘Trump to leave G7 early, tensions high after “rant” over trade‘: ‘U.S. President Donald Trump and Group of Seven leaders had a bitter exchange over trade tariffs, ratcheting tensions at a summit that he planned to leave early on Saturday… In an “extraordinary” exchange between the leaders on Friday, Trump repeated a list of grievances about U.S. trade, mainly with the European Union and Canada, a French presidency official told reporters. “And so began a long litany of recriminations…” the official said.’

- Following Trump’s departure from the summit: The New York Times noted: ‘President Trump upended two days of global economic diplomacy late Saturday, refusing to sign a joint statement with America’s allies, threatening to escalate his trade war on the country’s neighbours.’

- The Financial Times analysed: ‘Donald Trump capped a fractious meeting with G7 allies by refusing to back a joint statement from the group that had pledged to fight protectionism, blaming “false statements” from Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau and ratcheting up tensions on tariffs.’

What, therefore, explains the difference between the sharply contrasting SCO and G7 summits?

Part 1 – Economic Roots of Political Instability in the West

The Great Stagnation

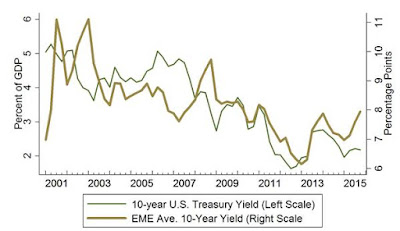

Attempts in sections of the media to present the situation in the Western economies as very favourable has led to a serious inability in such analysis to foresee or explain the clashes which took place at the G7 summit or other features of the geopolitical situation. The reason for this is that factually, far from being favourable, the Western economies are undergoing a ‘new mediocre’, in the words of IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde – what may be termed historically a ‘Great Stagnation’, in which Western long term economic growth is now astonishingly slower than in the ‘Great Depression’ after 1929.

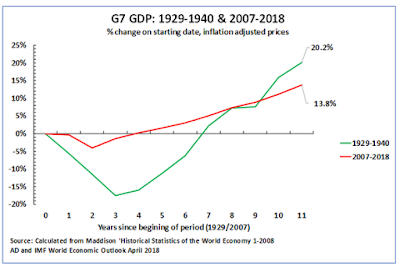

This historical comparison is shown in Figure 1. This shows the percentage change in GDP for the G7 economies as a whole compared to the peak year of the business cycle preceding the respective economic crisis– i.e. the years are counted after 1929 and after 2007, with in each case the number of years since that peak shown. The data for the period after 1929 is the actual economic results, for the period after 2007 actual factual data is used up to 2017 and the figure for 2018 is the latest IMF projection for this year. The situation for the G7 as a whole is clear:

- By eleven years after the crisis of 1929 the GDP of the G7 economies as a whole was 20.2% higher than in 1929. Considered in more detail, the downturn after 1929 was deeper than after 2007, but recovery was relatively rapid and fast. That is, in a sense, the 1930s is better thought of as the ‘Great Recession’ – i.e. sharp downturn followed by rapid recovery. The reason that the term ‘Great Depression’ is used, is due to the specific situation in the 1930s in the US.

- In contrast, by 11 years after 2007 the GDP of the G7 economies as a whole was only 13.8% above the pre-crisis level – i.e. growth in the G7 as a whole after 2007 was significantly slower than after 1929.

Figure 1

Examining the main G7 economies in detail, and comparing the same number of years after 1929 and after 2007, the last year before the international financial crisis:

- Eleven years after 1929, Japan’s GDP was 64% higher than its pre-crisis peak, whereas in contrast 11 years after 2007 Japan’s GDP was only 13% higher than its 2007 level. Therefore, by eleven years after 1929 Japan’s economic growth was almost five times as fast after 2007.

- By 11 years after 1929 Germany’s GDP was 44% higher than the pre-crisis peak, whereas in contrast 11 years after 2007 Germany’s GDP was only 15% higher than it pre-crisis peak. Therefore, Germany’s economic growth in the 11 years after 1929 was almost three times faster than its economic growth in the eleven years after 2007.

- By 11 years after 1929 UK GDP was 32% above its pre-crisis level, whereas by 11 years after 2007 UK GDP was only 13% above its 2007 level. Therefore, in the 11 years after 1929 UK economic growth was almost two and a half times as fast as after 2007.

- In the 11 years after 1929 Italy’s economy grew by 24%, whereas in the 11 years after 2007 Italy’s economy actually shrank by 4%. Therefore, in the period after 1929 Italy’s economic growth was far faster than in the period after 2007.

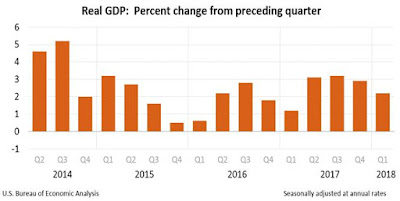

- Recovery in the US after 1929 was slower than in the other G7 economies just analysed. It took seven years for US GDP to recover to its 1929 level, and even then, recovery was weaker than in the G7 economies already analysed. Nevertheless, by 11 years after 1929, US GDP was 19.8% above its 1929 level whereas by the end of this year, the same 11 year period after 2007, US GDP will only be 18.3% above its 2007 level. That is, by the end of this year, US economic growth over the 11-year period since 2007 will also be slower than in the 11 years after 1929.

It was this recovery after 1929 of the US and three other major G7 economies – Germany, Japan, and the UK – which, explains why overall G7 growth in the 11 years after 1929 was significantly faster than in the 11 years after 2007. Only in two less important G7 economies, Canada and France, was economic growth in the 11 years after 1929 worse than after 2007 – but the weight of the relatively more minor G7 economies, Canada and France, was quite insufficient to match that of the US, Japan, Germany, the UK and Italy.

Political and geopolitical consequences of the ‘new mediocre’

Once this fact that the main Western economies, the G7, are going through a period in which their growth is slower than after 1929 is clear then the key present features of the geopolitical situation, in particular the ‘disorder’ in the West, become clear. Comparing the geopolitical situations after 1929 and after 2007, then following 1929 the extreme violence of the economic downturn led to extremely rapid political crisis:

- In 1931 Japan began war with China

- In 1931 Britain abandoned the gold standard, destroying the existing international monetary system.

- In 1932 Roosevelt was elected US President to launch the New Deal.

- In 1933 Hitler became Germany’s Chancellor.

But the strong economic upturn after the depth of the post-1929 crisis also meant these regimes, once established, did not face serious domestic political opposition – Japanese militarism was not met with major domestic popular disapproval, Hitler was popular in Germany, the British Conservative governments of the 1930s had some of the highest popular votes in British history, Roosevelt became the longest serving US President.

Therefore, while the 1930s, after recovery from the depth of the economic crash, was a period of great international geopolitical instability the domestic regime in the major countries was rather stable. The exception to this, France, which went through the mass strikes and turmoil of the Popular Front government in 1936, confirmed this rule ‘from the negative’ – France was the one major G7 economy whose economy in the 1930s grew far more slowly than after 2007.

This different pattern of economic development after 2007, compared to that after 1929, explains current geopolitical developments which create the international situation facing the SCO.

Whereas after 1929 very rapid economic downturn led to rapid political crisis the long period of slow growth, the ‘Great Stagnation’/’new mediocre’ after 2007, means that the political instability began slowly and has progressively accumulated.

- In 2010 rising political instability started in developing countries produced the ‘Arab Spring’ and widespread destabilisation in the Middle East.

- In 2012 Le Pen’s National Front achieved electoral breakthrough in France beginning the rise of ‘populist’ movements in advanced countries.

- In September 2015 radical left winger Corbyn was elected leader of the UK Labour Party, while in June 2016 the UK referendum voted for Brexit.

- In 2016 Trump was elected US President against the wishes of the establishment of both Republican and Democratic Parties inaugurating almost continuous clashes in US politics.

- In May 2017 Macron was elected French President against the opposition of both right and left wing traditional political parties.

- In 2017 Merkel suffered a severe electoral setback creating the most difficult period in forming a German government since World War II.

- In June 2018 ‘populist’ parties, the Five Star Movement and The League, formed a government in Italy.

Unstable geopolitical situation on the periphery of the SCO

This destabilisation, in its impact on developing economies, also explains the geopolitical situation surrounding the SCO.

- To the west of the SCO region an arc of military conflicts extends from west and north Africa (Boko Haram in Nigeria, al-Shabab in Somalia, failed state in Libya etc), extending into full scale war in Syria and Iraq, while to the west and north of the Black Sea, in Ukraine, armed conflict broke out after the 2014 coup d’etat and problems of jihadist terrorism continue in parts of the Caucasus.

- In one region of the south SCO war continues in Afghanistan.

- To the east of the SCO region the US continues to attempt to carry out provocative actions in the South China Sea and in the regard to Taiwan Province of China, while making military threats against the DPRK.

- With an impact on the entire global situation, the US has embarked on sanctions against Russia, tariffs against key US allies such as Japan, Canada, Mexio and the EU, sanctions against Iran, and now sanctions against China.

This geopolitical situation, in addition to its economic underpinnings, is worsened by the fact that US foreign policy has deliberately geopolitically embarked in recent decades on a policy in which it is prepared to accept an outcome of ‘failed states’ and the emergence of jihadist terrorist organisations. For example, in Iraq, prior to the US invasion of the country, jihadist terrorist were entirely marginal. After the US invasion, in the form of ISIS, jihadist terrorists controlled large parts of the country – indeed it is striking, and indicative, that at present the only parts of Iraq and Syria in which areas controlled by ISIS continue to exist are those were US forces are dominant. Similarly, in Libya US led NATO forces overthrew Gadhafi to create a ‘failed state’ in which large parts of the county were controlled by jihadist terrorist organisations which export weapons to large parts of Africa.

But as comparison to the 1930s shows, in addition to the impact on developing countries, very slow growth leads to increasing conflict between the advanced economies. Certainly, the present clashes between G7 member states are less than the full-blooded conflicts, culminating in war, between the US, Germany, Japan, the UK, Italy and France in the 1930s. But the increasing clashes between the G7 countries show, in a much milder form, the same trends.

Part 2 – Economic Roots of Consolidation of the SCO

The SCO

The economic contrast in the SCO region to that in the G7 is evident and is shown in Table 1 – this data is not taken from a source controlled by China, but from the projections of the IMF for economic growth in the period 2017-2023.

As may be seen, regarding the three largest G7 economies, which dominate the G7 group:

- The highest total growth in per capita GDP in any G7 country in the period up to 2023 is Germany’s 10.3%, with an annual average growth of 1.7%.

- Total US per capita GDP growth in the same period is projected to be 7.4%, an annual average 1.2% growth.

- Japan’s total per capita GDP growth in this period is projected at 6.4%, an annual average 1.0%.

In contrast:

- China’s total per capita GDP growth is projected at 39.4%, an annual average 5.7%.

- India’s total per capita GDP growth is projected at 46.0%, an annual average 6.5%.

- All SCO economies, except Russia and Kazakhstan, are projected to have faster per capita GDP growth than any G7 economy – and Russia and Kazakhstan are projected to have faster per capita GDD growth than every G7 economy except Germany.

The net result of much faster growth in the SCO region than the G7 is that, even measured at current exchange rates, total GDP growth in the SCO region is projected to be larger than in the G7 in 2017-2023 – $12.2 trillion compared to $11.1 trillion.

But measurement at current exchange rates significantly understates the real expansion of markets for companies in the SCO region compared to the G7. The reason for this is that lower wages in developing economies, not only in production but in distribution and retailing, mean that goods and services can be sold profitably in developing countries at lower prices than in advanced ones. For this reason, current exchange rates understate the size and expansion of developing economies compared to advanced ones.

The branch of economics that deals with this is known as Purchasing Power Parities (PPPs). This analyses the volume of goods and services produced in an economy taking into account the differences in price levels. It is, therefore, a better measure of the increase in volume of production of goods and services than measurement at current exchange rates.

As Table 1 shows, measured in PPPs, the increase in GDP in the SCO region, 23.0 trillion dwarfs that in the G7 at 9.4 trillion.

To complete the picture on the SCO, if SCO official observer states (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia) and SCO dialogue partners (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Turkey) are included the difference between the SCO region and the G7 becomes larger. The IMF projects increase in GDP in 2017-2023 in all SCO full members, observers, and dialogue partners at $12.3 trillion compared to $11.0 trillion in the G7. In PPPs the lead of all full members, observers and dialogue partners is 24.1 trillion compared to 9.4 trillion in the G7.

Given this much faster economic growth in almost all SCO members than in the G7, and greater total size of potential economic development in the SCO region than in the G7, it is clear all SCO states have a strong interest in maintaining conditions of geopolitical stability, in order to enjoy the fruits of this economic growth.

Table 1

South China Sea

To further analyse the reasons for ‘stability in the East’ a second decisive area surrounding China can be analysed – those countries and regions bordering on the South China Sea. This area is of particular importance because deliberate attempts have been made by the US to destabilise this region – the attempt to get the Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration to illegitimately rule on the region, provocative voyages by US warships in the region etc. Sustained attempts by the US to escalate tensions in the South China Sea region to high levels, however, have been unsuccessful.

To understand the economic background to this failure of the US efforts, it is striking that Table 2 shows that the IMF projects that every country or region bordering on the South China Sea will in the next period have a faster growth rate than every G7 economy. In particular between 2017 and 2023, in addition to China, the IMF projects:

- Malaysia’s per capita GDP will grow a total 23.8%, an annual average 3.6%.

- Indonesia’s per capita GDP will grow a total 28.1%, an annual average 4.2%.

- The Philippines per capita GDP will grow a total 32.3%, an annual average 4.8%.

- Vietnam’s per capita GDP will grow a total 38.0%, an annual average 5.5%.

Regarding overall economic potential growth in the region, the South China Sea region does not contain India, which together with China is the world’s most rapidly growing very large economy, but nevertheless the rapid growth of the states in the region means that the economic growth potential of the South China Sea region is essentially equal to that of the G7 measured at current exchange rates and much greater than that of the G7 measured in PPPs. The IMF projects that, measured at current exchange rates in 2017-2023, economic growth in the South China Sea region will be $10.9 trillion compared $11.1 trillion in the G7, while in PPPs the growth of the South China Sea region will be 17.7 trillion compared to 9.4 trillion in the G7.

Table 2

SCO and the South China Sea region

To analyse the situation in a consolidated way, the SCO and the South China Sea region include China, therefore the combined economic growth of all states in these regions in 2017-2023, as projected by the IMF, is shown in Table 3. As may be seen:

- Even at current exchange rates, considering only full members of the SCO, the economic growth in the combined SCO and South China Sea region is projected, on IMF data, to be significantly greater than that of the G7 – $13.5 trillion compared to $11.1 trillion.

In terms of PPPs the greater growth of the full SCO members and South China Sea region compared to the IMF is overwhelming – 26.8 trillion compared to 9.4 trillion. In summary, in PPPs, the best approximation of the real increase in markets for goods and services, the combined growth of the SCO and G7 regions will be almost three times than of the G7.

Table 3

Belt and Road Initiative

Finally, in analysing the broader perspective of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) a complication is that, unlike the SCO states or the South China Sea region, the area covered by BRI is not officially defined. Furthermore, the BRI has a specific feature that India, for political reasons concerning its border dispute with Pakistan in Kashmir, refuses to officially support the BRI – while in reality India fully participates in, and benefits, from economic development in the BRI region. Therefore, to calculate the economic growth in the Belt and Road initiative, in addition to that of the strictly defined SCO and South China Sea states, it is necessary to make assumptions regarding which other countries to include.

There is no advantage in exaggeration in serious matters, so here only a ‘narrow’ definition of the BRI economic potential will be included. The BRI region will be taken as SCO and South China Sea states plus the other remaining states of the former USSR (excluding the Baltic States) plus Iraq – other Middle Eastern and East European states are highly favourable to BRI but they are not included here. This means for present calculations including in a wider BRI region, in addition to the SCO and South China Sea regions, Turkmenistan, Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine, and Iraq.

Table 3 therefore shows what may be termed both a ‘narrow’ and a ‘wide’ definition of the economic potential in the area surrounding China in comparison to the G7.

- The ‘narrow’ definition of the economic potential in the regions surrounding China may be taken as only full members of the SCO and those states bordering on the South China Sea.

- The ‘broad’ definition of the economic potential in the regions surrounding China may be taken as all full members of the SCO, SCO observer states and SCO dialogue partners, plus states bordering on the South China Sea and BRI states as defined above.

It was seen above that even taking a narrow definition of the economic potential in the states surrounding China this is projected to be greater than the G7 in the period 2017-2023. If a ‘broader’ definition of the BRI is included, then the economic advantage of the region surrounding China, compared to the G7,is evident.

- At current exchange rates, in 2017-2023 the IMF projects the broad economic potential in the BRI region around China at $14.2 compared to $11.1 trillion in the G7.

- In PPPs, which more accurately reflects real sales, the advantage of the region surrounding China is overwhelming compared to the G7 – in PPPs 29.2 trillion compared to 9.4 trillion.

Geopolitical Consequences

The geopolitical conclusions of the economic trends analysed above are clear.

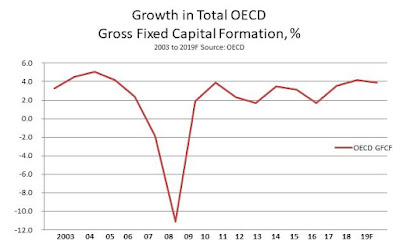

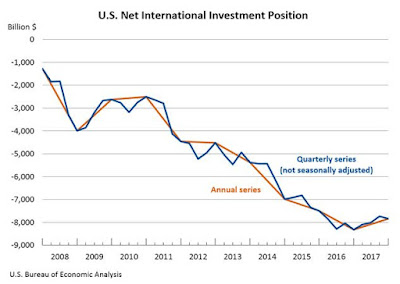

- The G7 is in a situation of the ‘new mediocre’/’Great Stagnation’, in which economic growth is even slower in the period after 1929. This necessarily produces domestic political instability within the G7 states, significant clashes between G7 countries as registered at the Quebec summit, and the development of significant terrorist threats, or even full scale civil war, in developing countries which are highly influenced by economic situation in the G7 – this instability surrounds the SCO region. It also explains the apparently irrational tariffs introduced by the Trump administration against China – the US cannot accelerate its own economy in the medium/long term and therefore for competition it conceives it has to concentrate on slowing China.

- In the SCO and South China Sea regions, in contrast, a high economic growth potential exists compared to the G7. This means that the states in this region have very strong incentive to reject destabilising activities promoted by the US and, instead to concentrate on economic growth.

It is these two different situations, in the areas dominated by the G7 and within the SCO, that produces ‘disorder in the West, stability in the East’. Failure to accurately analyse this situation, in particular the consequences of the ‘new mediocre’ in the G7, led some commentary in China to entirely fail to foresee the outcome of the SCO and G7 summits. The ‘disorder in the West, stability in the East’ is therefore not a purely temporary phenomenon but is based in fundamental economic processes. This same processes explain the introduction by the Trump administration of tariffs against China.

Conclusions

This underlying economic situation, however, does not mean that there are no problems confronting China’s geopolitical policy quite the contrary. But it means the nature of the situation must be understood accurately. In particular, in addition to the immediate problem of US tariffs against China:

- The slow growth in G7 provides a long-term basis for terrorism, failed states, and even full-scale warfare in a number of developing countries dominated by economic trends in the G7. This means the anti-terrorist and security functions of the SCO remain of extreme importance and challenges may be expected in these domains.

- The inability of the G7 economies to overcome the ‘new mediocre’, but a situation where the US retains global military superiority, produces a permanent temptation of the US to resort to military solutions and provocations. For this reason, both military reform in China and security cooperation between SCO members will be of great importance.

- The inability of the US to secure its goals by economic methods means the US will necessarily be tempted to take measures which are short of war against China but are deliberate provocations designed to create geopolitical tensions – for example provocations in the South China Sea, in regard to Taiwan Province of China etc

- While all states in the SCO and South China Sea regions have a strong mutual interest in peaceful economic development and cooperation there will be attempts by forces hostile to China to instead subordinate this to conflicts with China provoked by US neo-con forces – such US forces are particularly active in India and Vietnam. This, therefore, will require ongoing efforts by China’s diplomacy.

The apparently irrational actions by the Trump administration of introducing tariffs against China must therefore be seen as a symptom of the wider economic processes producing ‘stability in the east, disorder in the west’.

The above article was previously published here at Learning from China

Recent Comments