By Tom O’Leary

Workforce composition

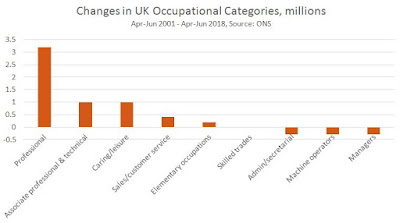

The overwhelming majority of this rise has been in the same two categories, Professional and Professional and technical occupations. Together over the last 17 years the number of people in these two occupational categories has increased by 4.2 million workers. This represents most of the net change in jobs over the last 17 years. The Professional category alone has almost doubled over 17 years.

Other important changes have also taken place, aside from these skills-based changes. Table 1 sets out some of the key changes in the composition and terms of employment over the same period. Rounding means some categories will not sum to the total.

The conscious and persistent efforts to widen the casualisation of the workforce have registered some victories over the period. Despite this it is important to note that the biggest single change in the workforce has been in the growth of full-time workers, representing more than two-thirds of the total increase.

Professional workers

They are not ‘Managing Directors’, senior bank executives, or managers of NHS Trusts and so on. These are in the first ONS category of Managers, Directors and Senior officials, and their number has sharply declined over the period, as shown above. Instead, they are teachers, doctors, nurses, accountants, finance and ICT professionals.

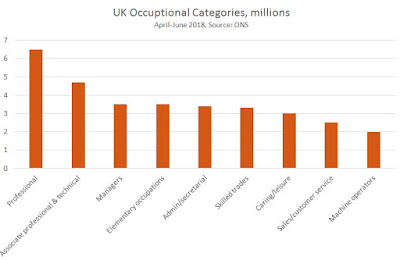

The five biggest categories of professional jobs all range between approximately 1 million and 1.5 million workers. In descending order, business and statistics (eg, accounting/auditing), teaching, health, ICT and sales jobs account for 6.57 million workers. This is of a total of 11.19 million workers in these Professional categories.

Clearly, there are different trends at work. The growth of the already outsized British finance sector has continued, registering little impact of the financial crisis. In addition, the tightening or at least greater complexity of the regulatory and accounting regime governing British firms continues to generate jobs, although the performance of British firms or their regulation has not noticeably improved. But firms are also increasing their capacity in certain limited areas, such as IT and in sales. At the same time, certain key (mainly public sector) jobs continue to grow in health, teaching and social welfare (including social work and housing).

Politics and workers

The current categories were re-designated in 2010 to reflect changing skills (nursing saw a big rise in required skill levels) but the current types of classifications were introduced in 1990. Other versions go back much further.

These categories are over 50 years old and are tool of advertising analysis used by publishers and advertisers in the National Readership Survey, solely in Britain. These are completely non-Marxist, that is non-scientific categories. It is arguable that there may have been some alignment between these categories and social classes when the NRS was formulated, but now they lead only to utter confusion.

The categories C2DE include both lesser-skilled workers, as well as those at the margin of the workforce and pensioners. It should come as no surprise to any observer of British politics that, unfortunately, pensioners overwhelmingly do not vote Labour. They are also the single biggest category, with over 12.5 million pensioners in the UK.

Similarly, it is widely arguedthat the Leave vote was a workers’ vote on the same spurious basis, and that the Remain vote was concentrated among the liberal, metropolitan elite. Northern Ireland and Scotland are not normally included in such categories, and they both voted Remain by some margin. So too did most of the cities including London, Leeds, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Bristol, Manchester, Cardiff and Belfast, Leicester and Newcastle. In general, workers live in cities and predominate there.

Class categories are actually based on social relationship to the means of production. Owners of the means of production are the capitalist class. Those who own virtually nothing except their own labour which they are obliged to sell are proletarians. Others form intermediary layers. The last several decades have in part actually been characterised by the proletarianisation of many professions, including teachers and doctors and other medics, as well as the numerical growth of those professions.

Likewise, a Labour victory depends on appealing to that combination of the workers and all the oppressed. These must first be correctly identified, taking account important changes and building support by championing the interests of the workers and the oppressed in their totality.

Recent Comments