By Tom O’Leary

All good jokes summarise or tell us something new about our society, or the times we live in, or about human nature. There is a very old, and very bad joke (repeated by Margaret Thatcher, among others) that, ‘The problem with socialism is that you run out of other people’s money’. It is a bad joke because it relies on a number of falsehoods.

There never has been a genuinely socialist government in Britain, and the largest and most famous economic crashes in this country have nearly all taken place under Tory or Tory-led governments. These were the depression of the 1930s and Churchill’s return to the gold standard, the Barber boom of the early 1970s, the Lawson boom of late 1980s and the imposition of austerity in 2010. The sole exception to this pattern was the crash under New Labour in 2008, which had adopted the Tory mantras of privatisations, PFI and bank deregulation.

Now, the new Prime Minister has adopted an economic policy he describes as ‘boosterism’. Boris Johnson as PM, or even as an architect of economic policy is itself a joke in poor taste. But the definition of boosterism under Johnson is simply promising anything in order to gain popularity.

This is important to grasp, as Johnson is not simply continuing Cameron/Osborne austerity. First, he has to get elected and is willing to scatter promises to achieve that.

Boris Johnson has form in this area. There is no garden bridge over the Thames, there is no ‘Boris Island’ airport, firefighter numbers were reduced and fire stations closed despite pledges to the contrary, and police cuts were only reversed when it threatened his re-election. The pledges were false, even where significant amounts of public money were spent.

Johnson’s current lies

Boris Johnson has effectively come to office after a coup against the previous Tory leadership. The electorate have not endorsed as Prime Minister, even indirectly, and pollsters have noted that his ‘bounce’ in the polls is far lower than Theresa May’s and is already fading – Labour is once again frequently marginally ahead in national opinion polls.

Under these circumstances, and leading a government which is supported by a bare majority that is the result of bribes to the DUP, Johnson does what comes naturally. He lies. He has promised:

- £1.8 billion for the NHS. This is a tiny amount compared to what the NHS needs and it has emerged since that £1 billion is not new money, and the source of the remainder has yet to be identified

- A total of £6.3 billion (£2.1 billion of which is new money) to prepare for No Deal Brexit, despite claiming it was a ‘million to one chance’ against happening

- 20,000 extra police officers, which is nearly as many as the Tories have cut since 2010, but says nothing about the similar numbers of police community support officers, and police admin staff that have also been cut over the same period

- More prison places and longer sentences, even though there are no new prisons and they would take years to build

- Full-fibre broadband across the country by 2025 – but no plan to achieve it, not even in outline, and no suggestion of the resources it would require

- To ‘level up’ per pupil funding in schools (which is aimed at Tory voters in the shires who complain about the greater funding for inner cities’ schools). The estimated cost for secondary schools alone is just £50 million per annum, a pittance compared the £4.6 to 5 billion needed simply to reverse Tory cuts to schools

- A tax giveaway to the higher paid, raising the higher tax band threshold from £50,000 a year to £80,000 (which benefits someone earning close to £80,000 or more much more than the benefit to those just above £50,000). There is no indication of the cuts elsewhere, to fund this giveaway, or a justification for the higher borrowing it would entail.

Politically, his agenda is aimed squarely at his own base, ‘with law and order’ measures to the forefront. Random stop and search will certainly increase the number of black and Asian boys harassed by police, but will do virtually nothing to halt crime, as Home Office analysis shows.

Boosterism and economic fundamentals

This string of false promises, untrue claims and distortions are widely believed to be associated with a planned general election campaign around the time of the Tories’ central project of a No Deal Brexit. As No Deal itself and the likely plans of a hard right Tory Cabinet represent a double blow to living standards, this will be discussed below.

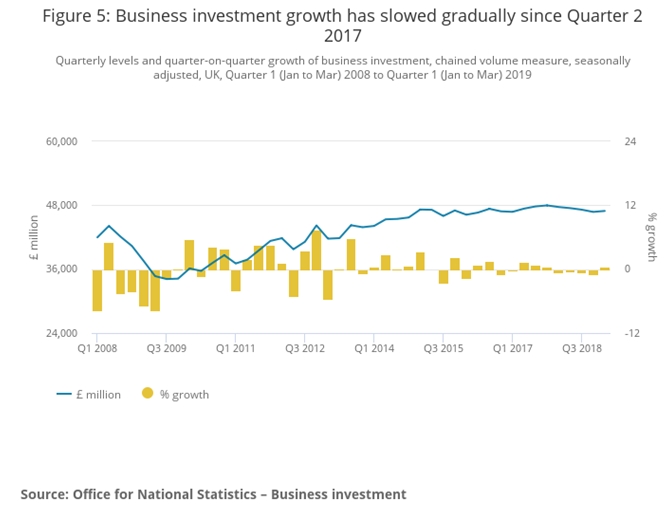

Yet, even before these two new blows to the economy and living standards, it is important to recall that the British economy is already in a crisis. The main source of this crisis is highlighted in Fig.1 below, reproduced from the Office for national Statistics (ONS). It shows that a weak recovery in business investment following the crisis of 2007 to 2008 has given way to outright stagnation and even decline. The economy has also begun to contract once more in the 2nd quarter of this year, in the recently-released preliminary data.

Chart 1. UK Business Investment

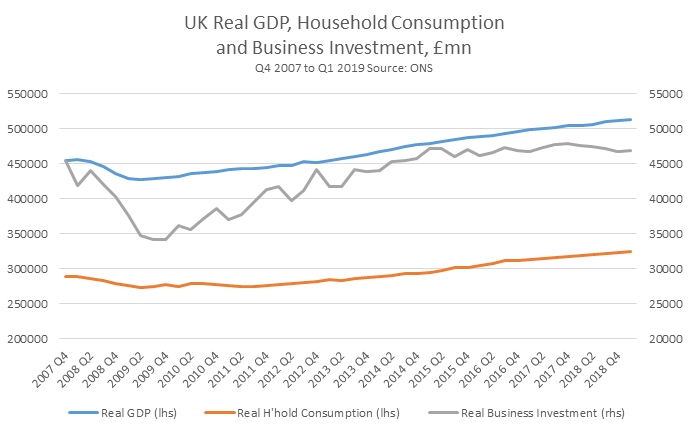

One way to illustrate how the weakness of business investment has been the main brake on growth and prosperity is by comparison. Fig.2 below shows that business investment has been far weaker than GDP growth since the beginning of the crisis. For illustration, business investment has also been far weaker than the growth in household consumption.

Chart 2. UK Real GDP, Household Consumption and Business Investment from Q4 2007 to Q1 2019

Since real Business Investment peaked in the 4th quarter of 2007 it has risen by just 3.25% to the 1st quarter of 2019. This is much weaker even than the growth in real GDP, which has risen cumulatively by 13% over the same period. In addition, it is often incorrectly asserted that the source of the crisis is the absence of ‘demand’, which is primarily Consumption. But real Household Consumption, which is the bulk of domestic demand has largely kept pace with the rise in GDP over the same period, increasing by 12.6%. In simple arithmetical terms, it is shown that the weakness of Business Investment is the main drag on UK growth.

But it is also possible to highlight this point in a more fundamental way. Consumption requires production – for most of us, even the apples we eat don’t just fall from the trees. They are commercially picked, processed, transported and sold by retailers. The main means of sustainably increasing that production is to add to the means of production through net investment, or to increase the number of hours worked.

Fig.3 below shows the growth rate in what the ONS calls the level of the capital stock (the means of production) over time, as well as changes in the net capital stock once the consumption of capital is taken into account. The consumption of capital is simply the capital that is used up in the production process, whether that is a rubber washer, a machine tool or a factory, which are each consumed or depreciated over different time periods.

Chart 3. Percentage change in growth rate of capital stock, net capital stock and capital consumption

The ONS summarises these trends as follows, “The UK’s net capital stock was estimated at £4.6 trillion at the end of 2017, increasing by 1.1% compared with 2016. Prior to the economic downturn, net capital stock increased on average by 2.0% per year, slowing to an average of 1.3% per year since 2010.”

Over the medium-term from 1997 onwards the annual growth rate of the capital stock has slowed from fractionally under 3% to just over 1%. As business is responsible for the bulk of the growth in the capital stock it is this prolonged deceleration in the growth of the means of production of the private sector that is the decisive factor in the medium-term slowdown and stagnation of the economy.

To raise the annual growth rate of the capital stock to 2% would require an additional £46 billion of fixed investment (which would itself need rise over time as this additional new capital itself depreciates).

Of course, set against this fundamental problem Boris Johnson’s ‘pledges’ of tax cuts for the rich and more spending on No Deal are simply another joke in poor taste. Failing to address this problem (unlike Labour, which promises to increase public investment) means that none of Boris Johnson’s pledges can possibly lead to economic growth or rising living standards over the medium-term. That is even without the damage from his central project, No Deal Brexit.

The threat of No Deal

A No Deal Brexit entails the severing of Britain’s close economic relationship with the EU, for the assumed benefits of a closer economic relationship with the US. But this is fool’s gold. In 2016, total UK trade with the EU (goods and services) amounted £554 billion, compared to £166 billion in total trade with the US (source, ONS).

There is no conceivable improvement in the trade relationship with the US that could even compensate for the likely fall in trade with the EU. At the same time, much of the country’s trade with other countries in the rest of the world is currently governed by trade agreements with the EU, and many of those are reluctant to offer the same terms to this country when it leaves.

More importantly, production in many sectors in the UK economy is closely linked through highly intricate supply chains to output in the EU. For many reasons, including geography these cannot be reproduced in supply chains connected with the US. Therefore any sector that has either tariff or non-tariff barriers will be faced with series of painful adjustments, including closure and relocation, with all the consequent loss of jobs.

There is too the obvious negative impact of the terms of any likely trade deal with Trump (and many of his possible successors). These range on everything from environmental standards to workers’ rights to food regulations and the accelerated privatisation of public services, including the NHS. In addition to China, Trump has already imposed tariffs and trade restrictions on neighbouring Mexico and Canada (effectively tearing up NAFTA), as well as India and the EU. This is in addition to the growing list of countries sanctioned for purely political reasons, such as Venezuela, Cuba, Iran, Syria and Russia.

But it is probably an error to assume that this government is even mildly uncomfortable with a US trade agreement that will increase fracking, sell off the NHS, reduce rights at work and allow US agri-business unregulated access to UK markets.

This is an ideologically hard right Tory Cabinet, many of whom, for example have explicitly advocated private health insurance or have financial links to it. Privatisations, fracking, ignoring the catastrophic risk of climate change and reducing workers’ rights can all contribute to an increase in labour exploitation and have the potential to boost profits.

For this government, and a small number of sectors, Trump’s demands can be seen as an opportunity, not a threat. The domestic beneficiaries of No Deal can include hedge funds and other speculative capital, private health insurers, private school owners and managers, frackers, sweatshop employers and landlords, as well as their apologists and PR agents.

For the overwhelming majority of the population a No Deal Brexit would have a very serious negative impact on living standards. It is also true of large sections of British capital. The fall in living standards has already been renewed with the fall in the pound leading to higher inflation and lowering real wages, as well as the job losses which have already begun simply from the threat of No Deal. No Deal will also reverse even the limited contribution to date of addressing the climate crisis.

Conclusion

Boris Johnson’s is a political campaign, where false promises are designed to win an election. They will do nothing to improve the economy or living standards for the vast majority.

Worse, his central project of a No Deal Brexit will deepen the economic crisis, by severing the closely inter-connected production supply chains within the EU. The replacement free trade deal with the US will only exacerbate the crisis and widen it to include policies which will add to the climate crisis, worsen public services and worker’s pay and conditions.

Labour already has the economic weapons to fight Johnson. Its fully-costed programme of measures to begin reversing austerity for the 2017 election amounts to £48.6 billion (pdf). This is massively greater than anything Johnson will ever promise, because it benefits workers and the poor the most. More importantly, as shown above, Johnson has nothing to say about raising the growth rate of the economy and living standards in a sustainable fashion. Labour does, with increased public investment and the National Investment Bank. It is also possible that Labour could build on its own successes of 2017, with additional funding for both, especially as interest rates are so low. But the defeat of No Deal is the next decisive step in Labour’s anti-austerity fight.

Recent Comments