By Tom O’Leary

The election plans laid out by the two major parties mean that it is crystal clear only Labour has policies to address the current crises (the LibDems can be disregarded in policy terms, as they only have one policy, which they claim is ‘stop Brexit’ but which is actually ‘stop Corbyn’). There are combined crises of the climate catastrophe as well as the stagnation of the economy and living standards.

The depth of the British economic crisis is not at all widely understood. It should be as only a proper appreciation of the scale of the problem can lead to the appropriate measures to tackle it, the policies that are necessary and the political choices that follow.

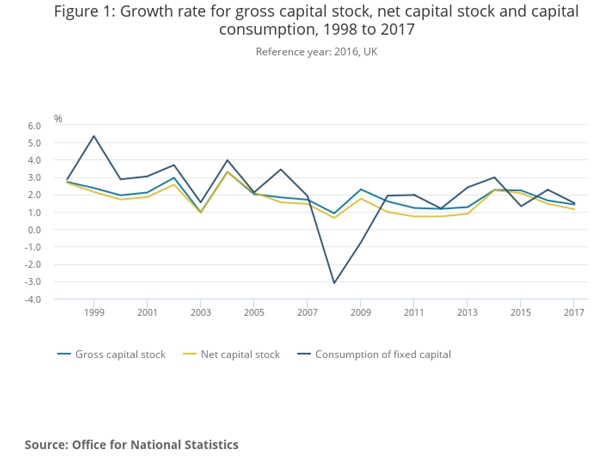

The scale of the economic crisis is illustrated in the chart below. Fig.1 shows the growth rate for the capital stock, the total value of machinery, factories, software, computers and so on used in the production of goods and services across the economy. Also shown are the growth rate in the consumption of capital, all the machinery used up in the production process, the equipment the becomes obsolete and the factories that become dilapidated. From this, the growth rate of the net capital stock can be derived, which is the growth rate of the capital once the capital consumption has been taken into account.

Fig.1 Growth in UK Net Capital Stock, 1998 to 2017

From 1998 to 2017 the annual growth rate in the net capital stock has fallen from 2.7% to just 1.1%. This exceptionally low level is a return to the earliest periods of capitalist development in Britain. In the 1760s as George III became the monarch, the growth rate in the net capital stock was about 1% annually. The only period which was significantly slower was in the exceptional period 1933-34, which saw an outright fall in the net capital stock, as part of the Great Depression.

This all matters because the net capital stock is effectively a measure of the fixed means of production for the whole economy. It is extremely difficult for the economy or living standards to grow sustainably beyond the growth rate of the net capital stock. The other main route is to increase the hours of labour, either by getting more people to work or getting the existing workforce to work longer hours. But without a rising level of the capital stock, the productivity of labour cannot rise.

At the same time, an increase in one specific area of the net capital stock is needed to tackle the climate crises. This is the required level of investment in the production of renewable energy as fossil fuels are eliminated. In addition, investment is also needed in energy conservation and in the reduction of energy consumption.

The Labour party policy precisely addresses this key component of the crisis by sharply increasing the level of public sector investment. Labour plans to invest £250 billion over ten years in a Green Transformation Fund to achieve all these aims.

Labour will also add a further £150 billion in a social transformation over 5 years to invest in infrastructure, transport, housing and capital investment in public goods such as health and education. The dilapidation of the schools and hospital will be tackled.

The contrast with the Tory plans is not mainly the inadequately small pledge of £20 billion per annum, or even the sharp U-turn in Tory government ideology about borrowing to invest (no more ‘magic money tree’ nonsense).

The main issue is that the Tory plans are completely fake. They are undeliverable under either Boris Johnson’s deal or No Deal, which is still an option and which is the clear preference of Trump. Under the government’s own forecasts, the British economy will be 9.3% lower than it would otherwise be in 15 years’ time with No Deal. Even if this forecast is accurate (and mainstream economics tends to underestimate the negative impact on investment), then the damage to government finances is likely to be very large.

To illustrate this point, the British economy did not recover to its pre-recession peak until the 1st quarter of 2013, fully 5 years later. This implies that the economy would have been about 12% larger if the recession had not occurred. Over that time and in later years, public sector debt trebled from under 30% of GDP to over 80%, including fierce austerity measures.

This gives some indication of the likely damage to government finances following a major negative development, either Johnson’s deal (which is just No Deal for just Britain) or No Deal for the UK. There will be no money at all for additional Tory public sector investment.

In fact, the long-standing ideology of the Tory party in favour of small state economics combined with the absence of any resources under their Brexit plans means that the entire government ‘programme’ of investment is a complete fraud.

The Cabinet ideologues, almost all of whom have voted for and written in favour of privatisation and outsourcing, have no intention of allowing a sustained increase in public investment. And Trump has no intention of allowing it either. His imposed deal will be the opposite, privatisation and outsourcing with US corporations at the head of the queue.

By contrast, Labour gets it. The scale of the ambition is in line with the objective environmental and economic crises within the constraints of the current level of public ownership of the economy. Looking ahead, one of the key benefits of a large-scale nationalisation programme is that the state would be able to have an even greater impact on the total level of investment in the economy. These are the real economic and environmental choices at stake in the election.

Recent Comments