By Tom O’Donnell

China’s socialism has achieved the greatest improvement in the living conditions of any major country in world history.

As a result, the economic policy of China in the construction of socialism should be studied closely, not just by socialists but also by anyone interested in economic development, increasing well-being for the population as a whole and in poverty reduction.

It is worth briefly restating some of those key improvements in living conditions, which ought to be the prime consideration for all economic policy making.

In 1949 China was one of the poorest countries in the world in terms of per capita GDP (Maddison). It has since already achieved ‘moderate prosperity’ using IMF designations and is on course to become a high-income economy on the same basis. In 1950, China accounted for just 4.6% of world GDP (Maddison) and now accounts for 18% of world GDP (World Bank data for 2022).

China has also provided the greatest increase in life expectancy in the shortest period of time in human history. At the time of the Revolution in 1949, average life expectancy was just 35 years. Now it is just over 78 years.

Finally, China has achieved unparalleled success in reducing and then eliminating absolute poverty. China has lifted more than 850 million people out of World Bank-defined poverty in 40 years, which is by far the greatest poverty reduction achievement in human history. It has also now, after considerable focused effort, achieved the elimination of absolute poverty.

Unsurprisingly, these achievements have sparked a growing interest in China’s economy policies as a key to economic development. In addition, in most parts of the world China’s economic advances have fostered the growth in trade. So there are reasons of enlightened self-interest in understanding these developments even among those who would never describe themselves as socialists.

In the Global South there is widespread interest in the mechanics of China’s progress. On a very much smaller scale, there has also been the emergence of a committed band of supporters of China in the main Western economies. Most, but not all, are socialists or communists, who identify with the gains of the Chinese revolution and who oppose the new Cold War encirclement of it.

This article is addressed to these two groups, in the Global South and the smaller forces in the Western economies who are certainly not opposed to China’s rise and in many cases are strong and consistent defenders of it. Therefore, any differences or disagreements with them on economic policy in China should be understood as ‘contradictions among the people’; that is a debate about the shared goal of the best way to proceed.

Yet among those supporters of China and their many accounts of its progress there are repeated analytical gaps, particularly around ‘reform and opening up’, as well as a concerted effort to claim there has only been continuity, not discontinuity in the evolution of China’s economic policy. This is not supported by the Communist Party of China, and it does not correspond to the facts.

The point is not to generate heat where there should be greater light. Instead, given the enormity of China’s economic advances, it is extremely important that a rounded and accurate view of them is presented, so that anyone wishing to learn from the Chinese economic marvel can apply its lessons accurately.

The present author has relied on four important publications written by supporters of China’s economic achievements, as well as on economic data. As will be shown, even among strong sympathisers or supporters of China’s achievements there remains a degree of confusion about the mechanics of those achievements.

In this analysis there are four points that are paramount. They are necessary for an accurate understanding of the decisive factors which propelled China’s economic development. Taking the most important factors:

- Was the de-collectivisation of agriculture after 1978, that is the introduction of the household responsibility system right or wrong?

- Was the decision to remove medium and small companies from state ownership right or wrong?

But once these two fundamental and structural questions have been answered, they entail further huge consequences, which themselves pose further questions:

- If agriculture is de-collectivised and small and medium enterprises are removed from state ownership, and as these are the largest in terms of employment, then large parts of the economy cannot be subject to planning, even if it was desirable. Is planning in the small and medium-sized enterprises more important than their economic development?

- Was the opening up of the economy to international trade right or wrong? Of course, if the economy is open to trade it is not possible to fully plan the economy because the international economic situation cannot be controlled by the central planners.

If China is judged to be wrong on the de-collectivisation of agriculture and the removal of small and medium enterprises from state ownership, then the authors making those judgments do not agree with China’s economic reform. Yet, if China was correct to take these decisions then it does not have an economic structure that was the same as the USSR after 1929 right up to its collapse.

This is because, despite heroic efforts to claim otherwise there is not a continuity of China’s economic policy either to the USSR or to the pre-1978 China economy.

Each of the publications referred to below is valuable, even though there are many disagreements. These are: Reform and opening up: Chinese lessons to the world (pdf), De Freitas; China’s quest for a socialist future, Hammond, Becker, Puryear; The East is still red, Martinez;and China’s great road, Ross.

Worth studying and emulating

No country could possibly copy the Chinese model of growth in all its particulars, as each country has its own unique combination of general economic factors which must be considered. However, how China has handled its own unique combination of those economic factors may hold general lessons for the economic development of all.

Shortly after the Chinese Revolution took place in 1949 the average annual per capita GDP was equivalent to $448 (Maddison). Almost no other country was poorer than this. Since landlords, usurers and other parasites were still numerous, naturally the incomes for tens of millions was far below even this average. For comparison, the average annual per capita GDP in Western Europe in the year 1,000 (after the fall of Western Roman Empire) was equivalent to $425 (Maddison). Yet, by 2008 per capita GDP had reached $6,725 in China, the same level as the leading Western European economies in 1957.

That is, almost 1,000 years of Western economic development had been achieved in 60 years. That is the scale of the Chinese economic advance.

China is now poised to become a high-income country according to World Bank designations. This means that the majority of the world will have average incomes below China, some very substantially so. As a minimum, residents of those countries, who are the vast majority of humanity, have every interest in studying the dynamics of China’s economic growth.

For socialists and all those simply interested in poverty alleviation, China also offers the greatest example of poverty eradication in human history. Using World Bank criteria, it has lifted 800 million people out of poverty. Its rise has transformed the lives of the greatest proportion of the world’s population in history. It also did so more rapidly than other periods of fast growth historically, in the Industrial Revolution, or with American, ‘railroad-isation’, or the Russian Revolution. China’s rapid advance after the introduction of ‘reform and opening up’ directly impacted 22.3% of the world’s population.

Most importantly, As John Ross said, “this unmatched speed and scale of China’s economic development was achieved by a socialist and not by a capitalist country and economy.”

3 phases of development

There are three distinct phases of China’s economic development post-1949. The first was the enormous social and economic achievements of the period from 1949 until Mao’s death in 1976. The second was the period of ‘reform and opening up’ from 1978 onwards primarily under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. The third phase effectively begins with the appointment of Xi Jinping as general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 2013, and addresses the problems of development from a moderately prosperous to a high-income economy.

This third phase is beyond the scope of this article. Unfortunately, these problems are not ones that most of the world as yet deals with. This article concerns itself with the earlier phases of economic development.

First, it must be acknowledged that the period of Mao’s leadership was quite extraordinary in terms of human development.

In the publications referred to above, there is a general consensus about how extraordinary these are (only De Freitas could be described as somewhat lukewarm). This should not be surprising.

Contrary to the myth of Mao the monster (which Martinez debunks easily) the accurate picture is one where there were huge advances in infant mortality, in longevity, in literacy, the position of women, the position of national minorities and a host of other indicators under Mao’s leadership.

Of course, it can be objected that, having defeated the warlords, the foreign occupiers and their allies, reunified the country and establishing peace, some of these indicators at least were bound to improve. But since all of these were a product of the Chinese Revolution itself, led by Mao, this simply demonstrates the extraordinary scope of the impact on people’s lives under Mao’s leadership, political, military, social and economic.

Amongst supporters of Chinese socialism these matters are largely uncontested. These achievements are so enormous that anyone who failed to recognise them should not be expect to be taken seriously either in China or as an analyst of it.

Why was reform and opening up necessary?

The table below shows the real GDP growth of the Chinese economy and the world economy in the period 1950 to 1978 (two years after Mao’s death, when ‘reform and opening up’ was introduced).

Table 1. Changes in World and China GDP,

1950-1978, Real international $bns

| 1950 | 1978 | Average annual % change | |

| World | 5,336 | 18,955 | 3.55 |

| China | 245 | 935 | 3.81 |

Source: Maddison, author’s calculations

Over the period after the Revolution and until the mid-1970’s the real GDP growth of the Chinese economy was steady but unspectacular. In effect, there was no qualitative difference between the growth rate in China and the average in the rest of the world. Crucially, Chinese growth was also substantially lower than some other countries in the region.

The implication is that the enormous social advances under Mao’s leadership (which were not at all generally taking place in the rest of the world) were primarily a product of policies of socialist redistribution. This reflected a conscious effort towards improving the lives of the poorest masses, with spectacular results.

But the fruits of redistribution begin to dwindle over time if there is not also a rise in production. For a poor socialist country such as China, this must also be through demonstrating the superiority of socialist production simply in order to catch up.

Both Martinez and Hammond et al obscure this truth by emphasising only the continuities of the socialist redistribution policies. What is largely ignored or downplayed is both the necessity of the reform and opening up process and its impact on growth and prosperity.

The astonishing successes of reform and opening up

In 1978 when the CPC, now under the primary leadership of Deng Xiaoping, introduced reform and opening up, China was still an agricultural society in which the peasantry numerically dominated.

Because of the predominance of agriculture, reform had to have as its foundation land reform and changes to the system of production. This was the corner-stone of the entire process and is frequently overlooked altogether.

Before outlining the process, the impact of it should be shown. This determines its objective importance, as well as its value as 1) the mechanism which has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and 2) a process which can be learnt from and adapted to achieve similar results elsewhere.

The comparison in Table 1 is now reproduced, but this time it is the impact of the reform process that is shown by comparison from 1978 onwards.

Table 2. Changes in World and China GDP,

1950-2008, Real international $bns

| 1978 | 2008 | Average annual % change | |

| World | 18,955 | 50,974 | 2.69 |

| China | 935 | 8,909 | 9.52 |

Source: Maddison, author’s calculations

The effects are clearly transformative. The growth rate of the Chinese economy is far greater than in the earlier and comparable period (which are roughly equal, 28 years versus 30 years). It also vastly outstrips the growth rate of the world economy, which had slowed over the period, while the Chinese economy sharply accelerated.

The post-Revolution economy moderately outperformed the world economy prior to reform and opening up. But after reform and opening up, it blew away the rest of the world’s growth rate.

Whereas in 1950 to 1978 the growth rate of the Chinese economy was barely above the world average (and therefore below many countries), now there is no major economy in the world which has matched China’s growth. From this basis, it is possible to vastly improve the lot not just of the average Chinese citizen, but particularly to vastly improve the position of the very poorest. This is exactly what the poverty eradication programme has achieved.

The mechanics of reform and opening up

Given the predominance of agriculture in employment, reform had to have as its foundation land reform and changes to the system of agricultural production. This was the cornerstone of the entire process. Yet it is frequently overlooked altogether even among supporters of China, such as Hammond et al and Martinez.

Yet if the key reforms are downplayed, there is no credible explanation offered either for the necessity of reform or its startling success. If China was going to accelerate beyond the average growth rate, major reform was required. As will be shown below, while these reforms have proved enduringly controversial, so much so that they are not endorsed by many China supporters, they are perfectly in line with the application of Marx and Engel’s thought (as well as Adam Smith’s).

Deng de-collectivised agriculture and stressed household responsibility, allowing peasants to exercise formal control (but not individual ownership) over land if they sold a contracted portion of their crops to the government.

The effect was to guarantee (crops permitting) the output from the agricultural sector which had previously passed into state hands for distribution among the population. At the same time the peasantry was provided with incentives to increase production beyond that portion which had already been contracted to an arm of the state. This led to a general, large and persistent increase in the output of the agricultural sector.

The growth in living standards arising from reform and opening up was decisively due to the success of these reforms.

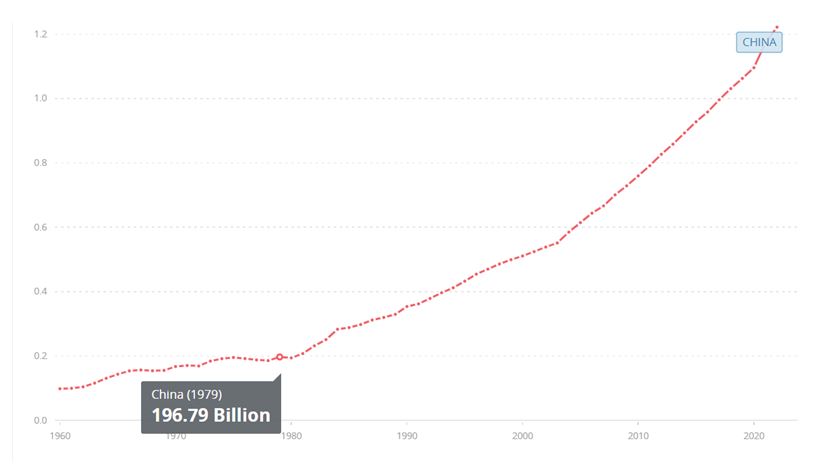

Chart 1. Agricultural output in China, 1960 to 2022, (US$ 2015)

Source: World Bank

The sharp acceleration in China’s economic output through reform and opening up is evident from the chart above. It took 19 years, from 1960 to 1979 for China’s agricultural output to double. But it doubled again in the following 14 years, then doubled again in the subsequent 8 years.

In parallel industry was reformed. Private businesses were allowed, administered prices for goods were abolished, foreign capital and know-how was attracted in order to develop production.

It should also be noted what was not done (on which there is general consensus among China supporters). The main banks all remained state-owned, as did the majority of the state-owned enterprises in sectors such as major transport, energy production and distribution.

The state remained in control and ownership of the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy. The paramount peak in the banking sector, which allows some direction of private investment but crucially, the state-owned sector as a whole can regulate the level of investment in the economy.

As investment is decisive for growth in the means of production, the state’s ability to regulate the level of investment is decisive for economic development as a whole. In doing so, China has not abolished the capitalist business cycle. It has simply not allowed it to determine the economy as a whole.

The land reform itself required further reforms. If this was not to be a one-off trick to hoodwink the peasantry, then the additional output had to be sold to the market. This meant the growth of private markets in the agricultural produce. It also meant representative prices, market prices which are integral to those markets and determine how the peasantry was to be rewarded.

A similar approach was adopted with regarded to vast numbers of private small producers, who were allowed to establish businesses, charge for their services, use market prices and competition to win customers. What may have started as a sector dominated by blacksmiths and motor mechanics now includes accountants, lawyers, hairdressers, and so on.

It was the surge in output of all kinds, the increase in economic activity in general across all sectors and the consequent rise in tax revenues which also contributed to the state’s large resources to intervene in and develop the means of production.

On all of this, many of China’s supporters are completely silent. It seems probable that some have in mind an alternative economic model – the ending of the New Economic Policy in the Soviet Union, followed by the forced collectivisation of the land, the exclusion of foreign investors and nationalisation of the overwhelming majority of the economy, all of which largely took place under Stalin.

Now, many have argued that this was all necessary in the certain knowledge that war was coming. It is not obvious that this policy was a complete success when the Red Army was defeated by the far smaller Finnish army in 1940 (which so encouraged Hitler in his genocidal assault). But it would require vast research and analysis to establish whether the policy of centralising production was the necessary response to inevitable war.

There is, though a real-world verdict on whether this policy worked in the post-World War II period. In a parallel with the post-Revolution period under Mao in China, in the first twenty years after the 1945, the Soviet model clearly outstripped the growth of the world economy. The world economy doubled in size over that period, while the Soviet economy trebled.

Yet from the early 197Os that stronger performance went into reverse, even though the world’s main capitalist economies were themselves suffering a sharp crisis (especially after the US tore up the post-WWII Bretton Woods economic order because it could no longer pay for social peace at home and pursue the Viet Nam War). Essentially, the comparative growth rates were reversed in that period. The capitalist world grew more rapidly than the economy of the Soviet Union.

It is possible that the Soviet economic model was a necessary retreat from Marxism in preparation for war. That is unproven. But the peacetime verdict on the same model (discounting individual and secondary policy choices) was not even as robust as a global capitalism in crisis. We can be certain that this model is not optimal, because, unlike China’s, it could not survive the international capitalists’ peacetime onslaught.

That the Chinese policy of reform and opening up were perfectly aligned with Marxism will be outlined in the next and final section of this piece.

But there is one further point that should be addressed in relation to a widespread misinterpretation of the reform and opening up process. This is the incorrect claim that Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was largely responsible for providing the resources for investment in the means of production that industrialised the economy and was the main spur to growth. This claim is made by De Freitas, Hammond et al and Martinez.

Naturally, if the transformational impact of reform and opening up is disregarded or downplayed, then logically there must be another factor at work which explains China’s extraordinary growth after 1978.

However, the explanation that it is FDI which played this role runs into two problems. The first is, it did not happen on anything like the scale required. The second is it assigns a magical role to the efficacy of private capital which it simply does not possess.

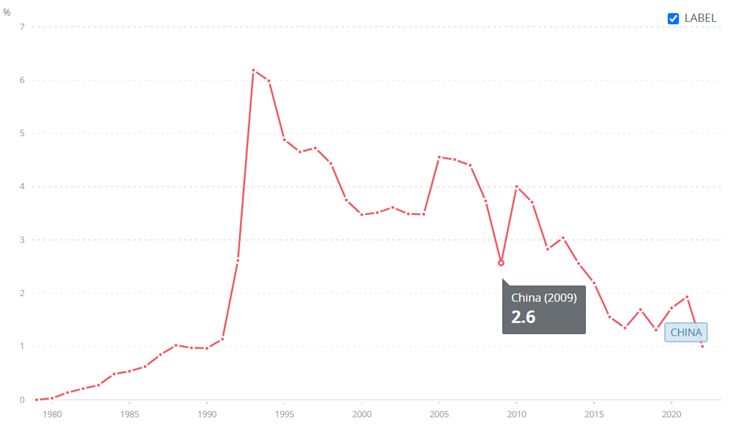

Chart 2. China Foreign Direct Investment as % of GDP, 1980-2022

Source: World Bank

Chart 2 shows the rate of FDI in China as a proportion of GDP. Contrary to widespread assertion, it is not a determining or even highly significant factor in China’s economic growth. It only exceeded 1% of GDP in 1992, long after China’s extraordinary economic acceleration had begun.

In addition, 1992 to 1999 was the only period in which China’s FDI was above the world average rate. Needless to say, the rest of the world did nothing to match China’s economic growth rate despite generally receiving higher levels of FDI.

More fundamentally, China has experienced double-digit GDP growth over large sections of that period. This is simply not feasible on the back of FDI rates that have mostly fluctuated between 1% and 3% of GDP. Even among strong supporters of investment in the means of production as decisive for growth, the textbooks would have to be torn up if such rates of return were possible.

Reform and opening up confirms Marxism

Finally, the reform process in China should not be treated as a deviation from Marxism, however successful. The truth is that Chinese economic policy and its success is precisely the application of longstanding Marxist economic theory on the development of socialism.

“The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.” – The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels

“Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.” – Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx

Adam Smith first identified the decisive role of the division of labour in developing the productive capacity of the economy. Famously, he showed a single person working on their own could not even produce a pin without the inputs of a large number of other producers.

Marx adopted and revolutionised this finding with the concept of the socialisation of production, including both the living labour of others and accumulated or dead labour through the means of production.

Therefore, in theoretical terms, a decisive question for all producers, including the hundreds of millions of isolated and impoverished Chinese peasants after the Revolution was how to connect them to the wider economy and allow them far greater participation in the division of labour.

For the workers of the countryside and the smaller number of workers in the towns and cities, the question of the socialisation of production was paramount if they were to achieve higher living standards, and so too, in all probability was the question of the survival of the Revolution.

But, as Marx argued (in one of his most widely misquoted passages) in the Critique of the Gotha Programme, the transformation in the direction of ‘right’; meaning fairness and equality could only begin on the basis of the already existing economic and social conditions.

There was no basis for large-scale investment in mechanised agriculture to produce an abundance of food in post-Revolutionary China. The level of accumulation was too low.

The route to the socialisation of agriculture under these circumstances would come from connecting that great mass of peasants and other small producers to the market. With contractual safeguards in place for the continued output of foodstuffs to the state for redistribution, peasants would be allowed to produce for their own account, and sell that produce at market prices.

It was understood too that de-collectivisation and incentives to production for the market would lead to inequality. This too is perfectly in line with Marx’s arguments in the Critique of the Gotha Programme, where the goal of communism would be to transform society ‘from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs’.

But this would only take place after a period where the old society determines the scope of that progress, and where labour is rewarded for its output. That is, for a more or less prolonged period, rewards would not be on the basis of need.

“In the first phase of communist society, The right of the producers is proportional to the labour they supply; the equality consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labour.

“But one man is superior to another physically, or mentally, and supplies more labour in the same time, or can labour for a longer time; and labour, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labour. …..But these defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society. Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.”

In addition, because the new society is born out of the old, capitalist system, with all its terrible defects, shortages and anarchy, then the task for the workers must be first the seizure of power then set about the twin tasks of wresting, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie and develop the productive capacity of the economy as rapidly as possible. As noted, above, this was the verdict of the Communist Manifesto, written long before the Critique of the Gotha Programme.

Note too, the differing timescales over the era after the seizure of power. The productive forces must be developed as rapidly as possibly, while capital must be wrested from the bourgeoisie by degree (emphases added -author).

This is precisely what happened in the period of ‘reform and opening up’. The Deng policy was obliged to include a partial reversal of the previous strategy for full collectivisation of the land. It had not worked, as it did not allow the vastly underdeveloped agricultural sector to participate fully in the socialisation of production on the basis of its existing economic and social conditions.

Finally, in the practical implementation of these policies there is no greater experience and no higher authority than the CPC itself. It is well-known (at least in pro-China circles) that it has issued a stinging criticism of the Cultural Revolution. It says,

“The Cultural Revolution was “the most severe setback suffered by the Party, the State and the people since the founding of the People’s Republic”. –

But in its (significantly less stringent) criticism of the Great Leap Forward, it also makes this important argument, that as late as 1958, “While leading the work of correcting the errors in the Great Leap Forward and the movement to organize people’s communes, Comrade Mao Zedong pointed out that there must be no expropriation of the peasants; that a given stage of social development should not be skipped; that equalitarianism must be opposed; that we must stress commodity production, observe the law of value and strike an over-all balance in economic planning; and that economic plans must be arranged with the priority proceeding from agriculture to light industry and then to heavy industry.”

These are the essential tenets of the reform and opening up process under the main guidance of Deng Xiaoping 20 years later.

But, more than the authority of any quotation or document, is the verdict of historical experience. China’s astonishing economic success took place because of these reforms, which correspond to the Marxist programme. The Chinese economy continues to thrive because the CPC has successfully applied the lessons of Marxist economic theory and practice to its own historical and national conditions.

If others want to learn from China’s experience in order to apply those lessons to suit their own economic and social conditions, the factual account must take precedent.

Recent Comments