By Paul Atkin

The contrast between the way the crises in steel production at Scunthorpe and Port Talbot has been stark. Both plants owned by companies based overseas. Both seeking a way out of unprofitable production. Both in negotiation for subsidy from successive governments for outcomes that would lead to massive job losses. Both looking to close aging blast furnaces earlier than originally planned because they have been making significant losses.

In the case of Port Talbot, this led to a deal to convert to Electric Arc Furnaces to secure sustainable steel production at the site, but with the loss of 2,500 jobs and only 300 retained. This was dependent on a subsidy from the government of £500 million. A similar deal was not clinched at Scunthorpe, as the crisis was brought forward by Trump’s imposition of a 25% tariff on UK manufactured steel – which led to an announcement of imminent closure from the company the following morning. A closure would mean 2,700 jobs lost – on the same scale as Port Talbot.

In Port Talbot, in the absence of a serious just transition process involving the unions, which were excluded from the discussions by the company and the then Tory government, the job losses are being dealt with by the same sort of offers of retraining as have been proposed for the Grangemouth oil refinery in Scotland. In the case of Scunthorpe, also with no just transition process, the government has rightly stepped in to take charge of the plant to keep the blast furnaces running in the short term; which means that the losses previously borne by the company will now be borne by the Exchequer. With the company losing £255 million a year, the governments £2.5 billion steel transformation fund can absorb this in the short term. Workers at Port Talbot have expressed some bitterness that this was not considered for them.

What has been different is the mobilisation of Sinophobia around British Steel’s ownership by a Chinese company, Jingye. Indian based Tata Steel’s ownership of Port Talbot was certainly mentioned in news coverage, but not on the blanket, verging on obsessive scale that British Steel’s Chinese ownership has. Tata’s brinkmanship in negotiations was also mentioned, but they were not accused of “negotiating in bad faith” in the way that Jingye have. Both companies have behaved as you’d expect a capitalist company to behave, though if you read Jingye’s Group Introduction you can see how their operations inside China are turned to more positive social objectives – from a high wages policy to greening their workplaces – from being based in a country run by a Communist Party, not by their own class. But here, both Tata and Jingye are in it for the money. Their UK operations have only been viable as a tiny loss making fragment of a much larger business, as part of an attempt to implant themselves in a variety of global markets in the hope of profitability in the medium to long term. Steel production at Port Talbot in 2022, for example, was just 10% of Tata’s global production of 35 million tonnes.

After Port Talbot, there have been no denunciation of Indian investment into the UK, nor any calls in the media or Parliament for any “urgent review” into India’s role in the UK, or paranoid accusations made explicitly by Farage but echoed by “senior Labour figures” as well as Tories in the media but not in the recent Saturday debate in Parliament, that the attempted closure in Scunthorpe is part of a dastardly plot by the Chinese government to sabotage a strategic British industry, not a commercial decision in which a company is seeking to cut its losses in all the ways British capitalist company law allows them to; including cancelling orders for the raw materials they’d need to keep running the blast furnaces they want to close. Instead, there has been serious negotiations with the Indian government to set up a trade deal, which was reported last week as “90% done”.

No decoupling there.

The attack on commercial engagement with China fulfills two objectives. One is a straightforward attempt to mobilise popular sentiment in defence of steel workers jobs behind a Cold War sentiment in a wider context in which the Trump administrations policies have shaken up popular faith in deference to the US. An anti Chinese attack distracts from that and pushes people back towards habitual hostilities.

The other opens another front in the resistance to any serious action on climate change that could threaten the profits of the fossil fuel sector. Accusations from the Right have been:

- The blast furnaces could have been kept running with locally sourced coking coal from the cancelled Whitehaven mine. This misses the point that the coke from this mine – had it been developed – would have had such a heavy sulphur content that it was too poor quality to be used at Scunthorpe, so this is a consciously mendacious and fundamentally unserious talking point.

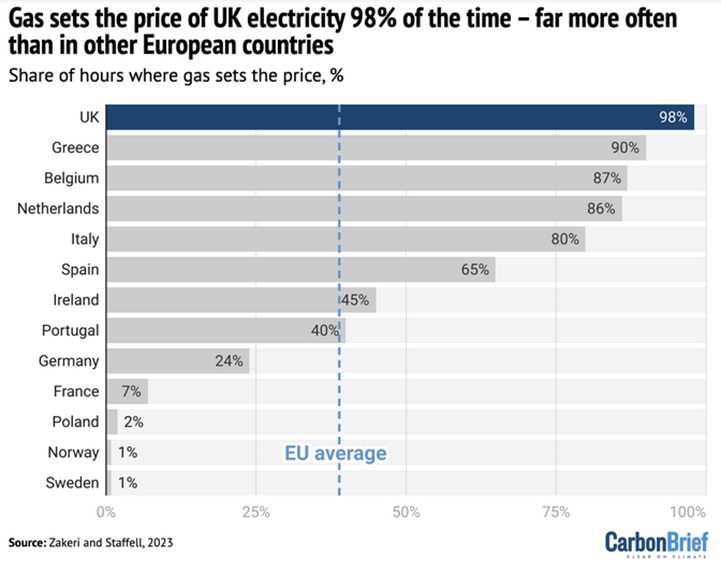

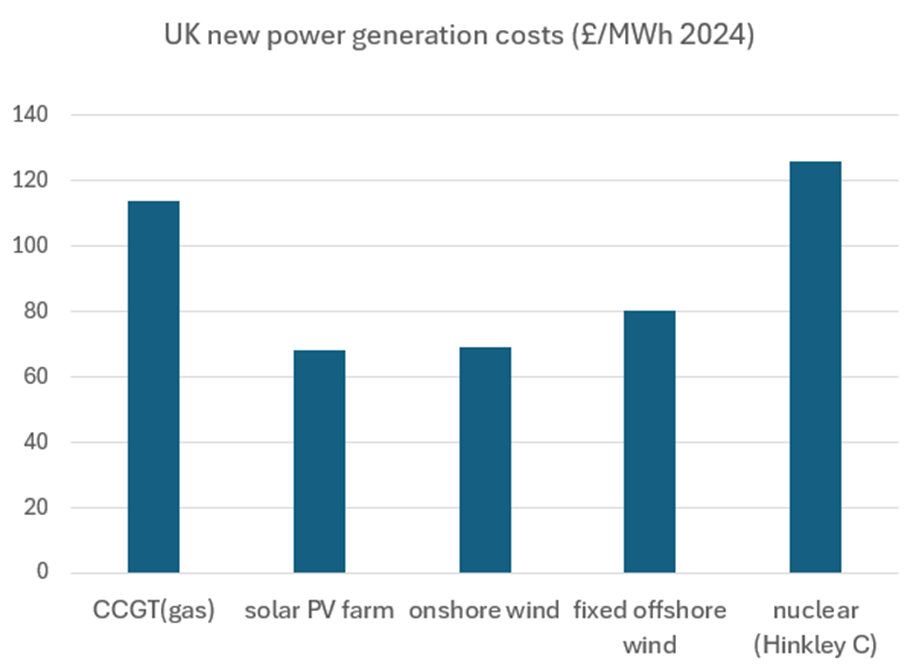

- High energy prices in the UK are because of “Net Zero”. This, as they know, is the opposite of the truth. The UK has high energy costs because they are tied to the price of gas far more than any other country in the G7. See Figure 1. We should also note that the oft repeated “solution” to this problem from Reform or the Tories is massive investment in nuclear power instead. The problem with this is that the cost per Kilowatt hour of energy generated by nuclear power is higher than gas, which is higher than renewables. See figure 2. So their way forward would actually compound the problem. Paradoxically, their attack on Chinese investment in UK nuclear power development, and the withdrawal of Chinese investment from Sizewell C in Suffolk and Bradwell in Essex, is making the financing of these projects almost impossible. So, in this case, the contradictions of their politics means they will neither have their cake, nor eat it.

Figure 1

Figure 2

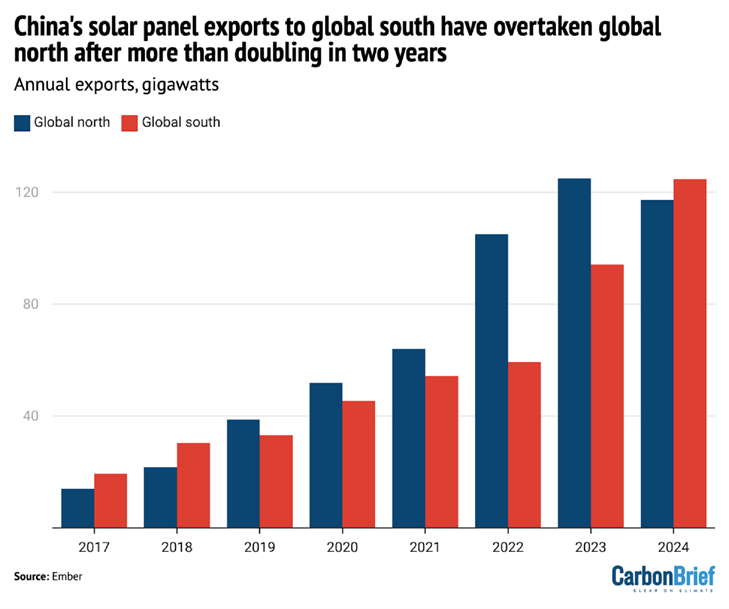

These themes came together in a front page broadside from the Times on 15th April directed at Ed Miliband’s recent trip to China aiming to improve relations and develop better sharing of expertise on the climate transition. Miliband’s is the head that the right wing press is keenest to have on its trophy wall of sacked ministers, hence quite limited and inadequate targets being described as “swivel eyed” and “eye watering” in a constant hammering of lead articles from the Sun to the Telegraph and all the low points in between. Attacks on solar panel installations are increasingly taking the form of accusations of “forced labour” in China, which are untrue, but because it is almost universally believed at Westminster, this threatens a reactionary result on the basis of an apparently progressive concern – as China is the source of 80% of the world’s solar panel supply. However, even if the UK sabotages its green transition by impeding imports of Chinese solar panels this will have little effect globally, as China is increasingly exporting them to the Global South. See Figure 3 Miliband is nevertheless the most popular government minister among Labour members in Labour List’s survey – in which he has a positive rating of 68, compared to Keir Starmer’s 13 – because he is seen as getting on with something positive and progressive, while Liz Kendall and Rachel Reeves are in negative territory.

Figure 3

The call from Dame Helena Kennedy for “an urgent security review of all those Chinese companies operating within our infrastructure which could pose a threat to our national interests – and maybe not just confined to China” threatens to compound the damage already done by the UKs removal of Huewei’s investment in the 5G network, ensuring that the version the country has is slower and more expensive, and the financial difficulty set for Nuclear power station projects by the removal of Chinese investment on the basis of “national security” paranoia. Applied more widely, this neatly lines the UK up with Trump’s trade war against China and sets the UK up for a potential trade deal in which US capital is looking hungrily at the NHS, wants to sell chlorinated chicken and other additive saturated and nutrition less food from their agricultural industrial complex and open up a tax and regulation free for all for their abusive big tech companies, while their President is actively sabotaging global progress towards sustainability by doubling down on fossil fuels. China is doing none of these things. A more positive approach is that being taken by the PSOE government in Spain, which is both encouraging inward Chinese investment – like the joint venture between CATL and Stellantis to build a battery factory in northern Spain and deals signed last year between Spain and Chinese companies Envision and Hygreen Energy to build green hydrogen infrastructure in the country.

Farage, and others on the Right are arguing for nationalisation as a temporary measure just in order for the company to be “sold on” – treating nationalisation as an emergency life support process for private capital -is that there is not exactly a huge queue of companies waiting to buy, and any that did would most likely to be looking at asset stripping. Jingye was the only company interested in 2019, when previous owner Graybull capital gave up on it.

This would also be the government’s preferred approach, because they are nervous of the capital costs involved in making the plant viable. There are three intertwined problems with this.

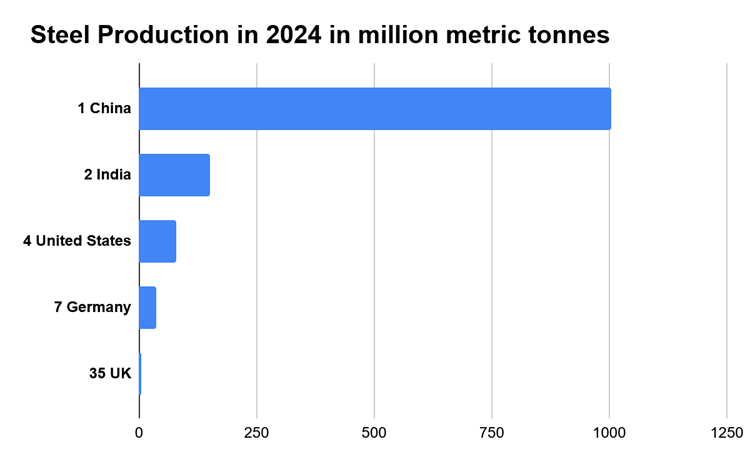

- Attracting a viable private company prepared to put serious money into reviving the plant means attracting overseas capital. Given that more than 50% of global steel production is made by Chinese companies (see figure 4 below) Jonathan Reynolds has changed his tune since the weekend debate in Parliament. That Saturday he was decrying allowing Jingwe into UK steel manufacturing as a national security issue, but by mid-week, a few days later, he was prepared to be more pragmatic about it.

- Making the plant viable cannot mean investing in new blast furnaces. These would become stranded assets before they had reached the end of their design life. Despite the determined rearguard action from Trump and others, trying to carry on as though the world isn’t changing makes no business sense. In 2024, for example, all new steel plants developed in China were Electric Arc Furnaces, designed to use scrap steel as raw material. As yet, production of virgin steel has been dependent on coking coal, but the first production using (green) hydrogen and electricity looks like coming on stream in Sweden by next year; so if virgin steel production is considered an imperative for the Scunthorpe site, that model will have to be looked at and emulated as a matter of urgency.

- New investment in different production on the site – like almost all capital investment – replaces labour with capital. As with Port Talbot, far fewer workers would be needed for EAFs. Reynolds has talked about “a different employment footprint” for the plant; which is one way to put it. So, the issue of how the transition can be made in a way that opens up alternative employment with decent terms and conditions has to be negotiated with the workers themselves through their unions.

What’s needed is a clear industrial plan that consolidates the nationalisation as a precedent for other sectors and builds on the Scunthorpe plant’s strengths in producing, for example, 90% of railway tracks used in the UK, as part of a strategic plan for green transition. This has hitherto been focussed on a transition to Electric Arc Furnaces, but linking the production of green hydrogen to new generation furnaces capable of producing the tougher virgin steel needed for a full range of industrial applications should also be part of the process; because blast furnaces can’t be kept open indefinitely if we are to stop the climate running away out of a safe zone capable of sustaining human civilisation by mid century.

Appendix

UK steel production is the 35th largest in the world, comparable to Sweden, Slovakia, Argentina and the UAE. Its 4 million tonnes in 2024 is just over a tenth of the production of Germany, a twentieth of the United States, a thirty seventh that of India and a 250th that of China. See Figure 4.

Figure 4

The niche, almost token, position of UK based steel manufacturing reflects a wider process in which UK based capital is no longer primarily engaged with manufacture.

The last time the steel industry in the UK was nationalised in 1967 it had 268,500 workers from more than 14 previous UK based privately owned companies with 200 wholly or partly-owned subsidiaries. These companies were considered increasingly unviable because they had failed to invest and modernise, so were increasingly uncompetitive. This is part of a wider story about how the UK capitalist class has transformed itself since the 1960s. While the quantity of manufactured goods has increased since then, the proportion of manufacturing in the economy has shrunk from 30.1% in 1970 to 8.6% in 2024. The service sector has grown from 56% to more than 80%. UK based capital primarily makes money from selling services, mostly financial, to manufacturing capitalists at home and abroad. They are spectacularly bad at large scale manufacturing start ups, as the debacle of British Volt (whose approach of setting themselves up a luxurious executive office suite before they’d secured funding to even build their factory might be described as cashing in on your chickens before you’ve sold any).

What that means is that most of “British Industry” is owned by firms based overseas, so might be better described as “manufacturing that happens to take place in Britain”. Consider the automotive sector. While there are locally based SMEs in the supply chain, all the big manufacturers depend on overseas investment. Nissan, Stellantis, BMW, VW, Geely, Tata (again). As with locally based steel production, firms like Morris, Austin, even Rover, are long gone for the same reasons as BSA – once the world’s biggest motorcycle company – now only builds retro classic designs as a niche luxury product and Guest Keen and Nettlefold had to be nationalised to save its assets.

Recent Comments