By Michael Burke

The whole world is caught up in the negative effects of Trump’s tariffs. But the US Administration’s principal target is clearly China, which has been singled out for extortionate levels of trade tariffs, combined with threats to third countries who continue to trade with China.

At the same time the rest of the world has been subject to far lower, but highly damaging tariffs, with the threat of further actions to come. A further consequence is the impact on the US itself, with the prospect of much lower growth, higher prices and job losses now widely anticipated. This in turn has caused turmoil in US financial markets and has led to the unusual situation where all main US assets, the stock market, government bonds and the US Dollar have all fallen at the same time.

The main questions posed are:

- Why has Trump conducted policy in such a reckless manner?

- What will be the effects of the tariffs?

- What are the long-term consequences?

Falling behind China

The context of the US economy’s weight in the world in framing Trump’s policies. The US economy has been growing at a considerably slower pace than China since at least the late 1970s and the beginning of the Chinese ‘reform and opening up’ period. For much of that time, this was of little consequence to the US.

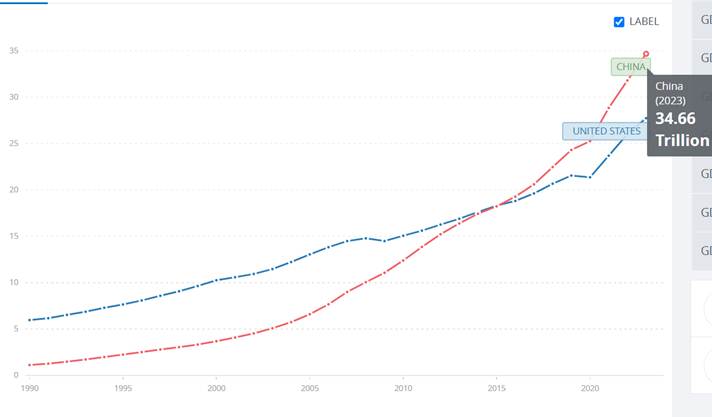

But in terms of economic size (using Purchasing Power Parities, PPSs, to measure real output and ignoring the effects of currency differentials), the World Bank calculates that the Chinese economy surpassed the US economy in 2016, as shown below.

Chart 1. Chinese and US economies’ real GDP (PPPs)

Source: World Bank

The World Bank now estimates that the output of the Chinese economy was $34.66 trillion in 2023, versus $27.72 trillion for the US. This makes the Chinese economy effectively 25% bigger.

But the growth trends in the two economies are making this disparity an urgent matter for the US. This is because the growth gap continues to widen rapidly.

This is illustrated in the recently published IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) database (April 2025). On their projections, by the end 2030 the US economy will be $37.15 trillion (PPP terms), while the Chinese economy will be $54.23 trillion. This means that by 2030 the Chinese economy will be 46% bigger than the US. For comparison, just six months ago in the October 2024 WEO, the IMF projected that by end-2029 the Chinese economy would be 38% larger than the US economy.

Over a slightly longer time frame, it is easier to see why there is a sense of urgency, even reckless urgency, from the Trump Administration. The US economy has doubled in size in last 17 years, according to World Bank data, while Chinese the economy doubled in size in 9 years. If both economies maintained that trend from their current starting points, the Chinese economy will be double the size of the US economy in little more than a decade. It would be four times the size of the US economy in 20 to 25 years’ time.

So in a very few years, on current trends, the Chinese economy will be out of sight compared to the US economy. The US will have decisively lost its position of global economic dominance and all that goes with it.

As this would be a world-historic defeat for the US, it is not something that its ruling circles are willing to accept at all. The ultra-aggressive stance on tariffs reflects both the scale of what is at stake and the urgency of their response.

Tariffs and how they operate

It has been widely shown that the supposed logic for the scale of the tariffs for each country is completely spurious. This is further underlined by the repeated changes to the tariff levels and, the date of their implementation and the the exemptions in certain sectors (and the U-turns).

This is because the tariffs themselves, while having a serious negative global economic effect are essentially politically determined.

At one end of the scale is a country like Britain, which regards itself as a close ally of the US, which has been hit with general tariffs of 10%, with 25% on cars and possibly more to come on pharmaceuticals. As noted previously, China is regarded in the US as its principal rival, if not enemy, and has been hit with 145% tariffs. This is effectively an attempt to end US-China trade. It is reinforced by the US threat of further sanctions on theird countries which continue to trade with China.

The negative effects for the global economy are widely acknowledged, if somewhat understated in terms of the impact on the economies of the Global South. In the April 2025 WEO, for example, the IMF slashed growth forecasts as a result of the tariffs, while simultaneously raising inflation forecasts for the advanced industrialised countries.

By contrast, UNCTAD, the UN trade agency is much more pessimistic. UNCTAD forecasts that global growth will slow to just 2.3% this year, which below its marker for world recession of 2.5%. UNCTAD says “developing countries and especially the most vulnerable economies” will be hardest. This is because, as UNCTAD argues, many low-income economies now face a “perfect storm” of tariffs and lower trade, existing unsustainable debt levels and slowing domestic growth.

It should also be remembered that an immediate casualty of the tariffs is the US economy itself. Although Trump continues to insist that the US is financially benefitting from tariff revenues, this cannot be true. This is because tariffs are never paid by the exporters, but by the businesses and individuals who are importing the goods. This means US businesses and consumers are paying Trump’s tariffs, which will reduce incomes in the US itself. It is in effect a Federal tax on the imports of US economy, whether for investment or consumption purposes.

Trump’s other key claim in favour of traiffs is that they will lead to ‘re-shoring’ of jobs. This is based on the false assumption that the jobs naturally belong in the US, and by punishing other countries and damaging their ability to export to the US, production will relocate to the US. Again, this includes all countries in its scope, but is particularly aimed at China.

The entire framework for this policy is shot through with contradictions and false assumptions. To highlight just some of the more important ones:

- The US economy now accounts for something over one quarter of world GDP and a little over one-eighth of world imports. Unless any country is almost wholly dependent on US imports (and for most of the world China is now a bigger trade partner) then higher import tariffs to the US will tend to force diversification to other markets (including into domestic markets) rather than economic collapse. Even for countries such as Mexico and Canada, the tariffs are so damaging and other demands from Trump so stringent they too are probably forced to diversify away from the US.

- Advanced manufacturing is increasingly complex, capital-intensive and relies on global supply chains. Price (and raised prices via tariffs, or the cost of labour) are just one element in the question of the location of production. Access to high skills, openness to the required supply chains, access to raw materials and reliable energy sources, highly developed infrastructure and a large, growing domestic market are all key factors. In many instances, the US simply does not offer these prerequisites.

- The same issues apply to re-location as to location. The world is not obliged by costs to relocate to the US. In fact, in light of the tariffs to be paid by relocating to the US, there is an incentive to seek alternatives.

- Tariffs have been tried in the recent past, with little success. There was a roughly 10% increase in US manufacturing jobs in the years following both the tariffs of Trump’s first term and coming out of the pandemic. But neither of these were ‘re-shoring’ as world manufacturing jobs increased at a greater rate over the same period.

In effect, Trump’s policy is to lay siege to the whole world in order to isolate China. However, given the US weight in the world economy and global trade, as well as the enormous complexity of global supply chains, with China often at their hub Trump, he risks the main effect is to isolate the US economy.

Trump’s gambit

In any contest where one side is decisively losing, a high-risk strategy may become appealing for them. The increased risk contains its own pitfalls, but opens the possibility of eventual victory, which is more attractive than inevitable defeat.

Trump’s tariff policy is incoherent and unworkable, for reasons noted above. Fundamentally, they cut across a decisive factor of economic development. The necessary condition for optimal economic development is the fullest possible participation in the international division of labour (or more accurately, the socialisation of production).

For fledgling industries or even economies, protectionist tariffs can be a useful tool for economic development, with the intention to lower those tariffs when there has been sufficient development and participation can actually take place. But for advanced industrialised countries like the US, tariffs entail cutting off the economy from participation in the international division of labour.

The same applies too to protectionism in other advanced industrialised countries in the G7. Protectionism, subsidies without sufficient investment and ‘buy domestic’ campaigns just lead to a cycle of higher prices, low investment and decline. The EU was born as the European Coal and Steel Community behind tariff walls (with Britain treading the same path, sometimes independently) but now there is very little steel, coal, shipbuilding or other industries which are thriving in the rest of the world. Cars may be next.

But Trump’s tariffs are not designed to succeed by economic means. They are a device to politically re-engineer the world in the US’s favour.

As previously noted, China is the principal target for the US, as the singularly extortionate tariff levels show, the absence of a 90-day pause and the threat to third countries continuing to trade with China. The much softer but damaging tariff threat to third countries is designed to enlist those countries on the US side in the trade war with China. Even then, there will be a price to pay as Trump seeks to enrich the US at their expense. This aligns with his military policy, also increasingly directed at China, with strong pressures on other NATO countries (and others) to ramp up their funding of the US war efforts.

The tactic is to force other countries to choose the US over China as a trading partner, cemented by the US’s long-standing military dominance over all other countries. Clearly, China’s rejection of Trump’s various demands and ultimatums means it has no intention of acceding in its own demise.

But there are a number of other economies which have sufficient weight in the world economy and provide crucial links in global supply chains, which mean they have both the capacity and incentive to resist Trump’s enforced choice. Principally, these are the EU, India and Japan.

It is unclear ultimately how they will respond, but surprisingly militant and public pronouncements from Japan suggest that Trump will not get things all his own way. Many other countries simply cannot choose the US over China because of existing trade relationships, or have very little incentive to, given China’s active role in their economic development. This is especially true in poorer parts of Asia, much of Africa and some countries in Latin America.

By contrast, the incoming German Chancellor Merz is reported to have offered Trump a zero-zero tariff regime on trade. Others who have offered the same have been rebuffed by the US. But zero tariffs (and presumably alignment on food standards) would devastate European agriculture and cause huge social unrest.

The Trump offensive is also not confined to overseas opponents or enemies. It is also a two-pronged attack on American workers and the poor. In this way, Trump aims to increase the profits of major corporations and their share of national income.

The first prong is a direct attack on social spending with $2 trillion in planned government spending cuts. The largest slice of this is a planned $880 billion cut to Medicaid and other federal healthcare programs. But the second prong is inflation. Since the financial crisis of 2008 it has proved very hard for Western governments to cut nominal wages via austerity. It has been much easier to cut real wages by stoking up inflation, which began in the US in early 2020. Not only will the effect of tariffs be to increase US (and other) rates of inflation, that process will be reinforced by a simultaneous $1 trillion tax cut which will overwhelmingly benefit the ultra-rich.

Inflationary tax cuts for US oligarchs and social spending cuts for workers and the poor are a blatant class war approach to fiscal policy. It remains to be seen what resistance these policies meet from those most badly affected.

Finally, there is the Achilles’ Heel of Trump’s policies in the form of US financial markets. Typically, stock markets rise with improving sentiment on the economy, while bonds rise as economic optimism fades. The global dominance of the US Dollar should mean that either one ought to be the international ‘safe haven’ in a time of political and/or economic turmoil. But in response to Trump’s policies both main US financial markets have fallen simultaneously, along with the US Dollar itself. This directly impacts the market wealth of millions of Americans, and particularly the set of oligarchs that Trump represents. Any softening of the tariff policy is greeted with huge relief in these financial markets; every new threat from Trump provokes a renewed sell-off.

Conclusion

This combination of linked factors; China’s refusal to be subordinated, other countries’ reluctance, the conflict with American workers and the fragility of US financial markets all mean that Trump has lost the first battle in this war, as even arch neo-liberal outlets like the Wall Street Journal acknowledge. ‘China called Trump’s bluff and seems to have won this round’, was its verdict.

But following from the analysis above, and the incredibly high stakes for the US, we can be certain that there will be many more rounds to come. The whole world will be affected for many years to come.

Recent Comments