Economics and the debate on immigration IIBy Michael Burke

The now notorious UKIP poster which suggested the entire population of the EU might come to Britain for work is designed to whip up racism. But it contains two fallacies that are unfortunately shared by many people who are not racists, and are therefore worth rebutting.

Myth 1

The first myth is that Britain is a uniquely attractive place within Europe in terms of pay or workers’ rights, or social security entitlements. The graphic below was produced by the UNITE union in Ireland in their argument for higher pay. But it is such a good graphic it is worth reproducing as it stands.

The compensation for British workers is among the lowest in Western Europe. Britain is not a uniquely attractive destination for economic migration within the EU. Therefore it should come as no surprise that Britain has one of the lower levels of immigration of the Western European economies.

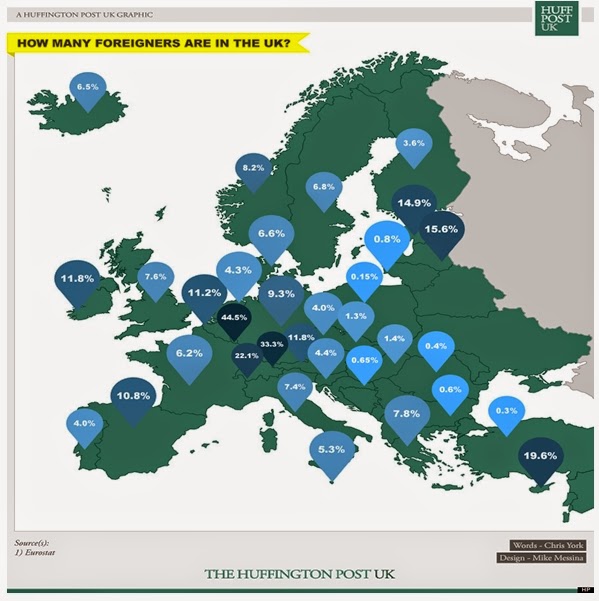

Another graphic, this time from the Huffington Post, illustrates this point very neatly. It shows the level of immigration (the total stock of migrants) as a proportion of the total population. (The data source is also Eurostat).

Myth 2

The second myth is that immigrants ‘take’ jobs or drive down wages. If that were true, then the introduction of the single market in the EU and with it the provision for the freedom of movement of labour would have led to a convergence of both unemployment and pay rates across the EU.

But we have already noted that the highest pay is in many of those countries with the highest levels of immigration. The same can be said of unemployment too. Immigrants have neither increased unemployment nor driven down pay in those countries. In fact, there has been a divergence in rates of pay in the EU over a prolonged period despite increased mobility of labour.

The argument about immigrants ‘taking jobs’ or driving down pay has strong echoes of (male-dominated) labour movement opposition to women’s entry into the workforce. Exactly the same arguments were used. From an economic perspective the country of origin or the gender of the worker is immaterial. What is relevant is the skills and adaptability of the workforce as a whole.

This is because there is not a fixed ‘lump of labour’ in the economy, which immigrants, or women (or young workers) detract from. If there was a fixed amount of available labour no economy would ever be able to grow, even via the birthrate. Instead, economic activity grows and prosperity increases with what Adam Smith identified as the division of labour and what Marxists understand as the socialisation of production.

In the fastest-growing economies of the word, such as China and India, workers frequently migrate internally over vastly greater distances than is required in a move from one small corner of Western Europe to another. Sometimes too, the cultural and even language barriers are also greater.

This migration is a key factor in the growth of all economies. It is primarily responsible for the somewhat better performance of the US economy compared to the EU over a prolonged period. The absence of immigration also partly accounts for Japan’s long-term stagnation.

This is because the movement of labour is a necessary counterpart to the increase in the division of labour, or the socialisation of production. It increases both the size and the capacity of the whole economy. This in turn means that effects of the division of labour are magnified. As a result, immigrants increase jobs as whole. In Britain, 14% of new jobs are created by immigrants (approximately double their proportion of the population).

Consequently, any restrictions on the freedom of movement of labour within Europe will not create jobs but destroy them. They will not underpin pay, but will serve to drive it down. Labour MP Frank Field, who is strongly anti-immigration and in favour of restricting free movement of labour within the EU is explicit on this matter. If migrants are stopped from entering Britain to work, those on benefits can be forced to do the work instead. His anti-immigration agenda has nothing to do with protecting workers rights or pay. It is an agenda which supports the interests of capital, not those of labour.

There are some who mistakenly believe there is a genuine left-wing case for curbing immigration. But this is completely wrong. Immigration is a function of increasing prosperity and tends to reinforce it. The only effective way to reduce immigration in Britain is to lower living standards, reduce real pay and increase poverty. It is Britain’s relative decline in living standards which explains which it has lower immigration than most of Western Europe. There is no genuine left-wing case for reducing immigration.

The alternative is a policy aimed at increasing prosperity which is necessarily accompanied by increased immigration. Prosperity and immigration versus poverty with immigration curbs. That is the real policy choice.

Recent Comments