Pounded by Brexit

By Tom O’Leary

The British economy is extremely dependent on inflows of overseas capital. As a result, it is one of the last countries that should ever contemplate leaving the EU without a serious plan for reviving the economy with investment and trade. As we now know, no such plan exists, serious or otherwise. Instead the theme of the Tory party conference was not ‘Britain open for business’ or a similar claim of questionable authenticity. The message from the Tories was simply ‘foreigners go home!’.

Unfortunately, for the overwhelming bulk of the citizens of this country wherever they were born, the practical understanding of economics by major international investors is considerably greater than the leadership of the Tory party. Those overseas investors whose willingness to lend to Britain is decisive for living standards understand that any country whose government insists on cutting itself adrift from the world’s largest trading bloc, is reckless about its economic planning and which is determined to push out a section of its workforce vital to its prosperity will not hold the same attractions for investment as previously.

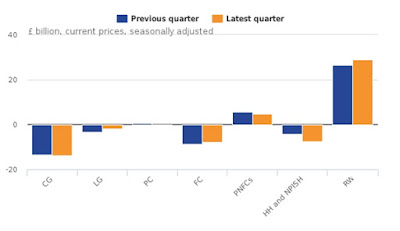

Chart 1 below shows the financial balances of different sectors of the economy over the last two quarters. The Rest of the World represents overseas investors, by far the biggest lender in the economy as a whole. In the first and second quarters of this year overseas investors lent the UK economy £26.5 billion and £29 billion respectively, much larger than in the same period last year. Without this lending the other sectors of the economy combined would have to sharply increase their own savings/reduce their borrowings. This would entail a sharp reduction in expenditure, either falling Consumption or falling Investment or both in order to bring the domestic sectoral borrowing and lending into balance.

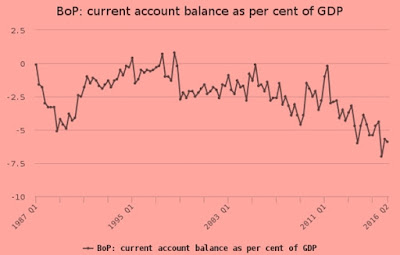

The sharp deterioration in the current account balance has arisen because the persistent trade deficit has combined with a fall in the level of payments from overseas that the UK economy receives from its holding of overseas financial assets. This seem to be linked to the shrinking and international retreat of the UK-based banks in the wake of the financial crisis and their forced sale of overseas assets, or their most profitable assets.

The UK economy is therefore extremely vulnerable to any decline in an overseas willingness to lend. If this occurs it must be countered by a relative decline in living standards, a forced reduction in expenditure (private or public, Consumption or Investment) and higher interest rates to attract overseas investment, or some combination of these.

There is of course no zero bound on the lending of overseas investors to the UK. Instead of merely reducing their lending and/or demanding a higher interest rate to do so, they may become net sellers of the considerable UK assets they have built up over previous decades, pausing only to pick up some newly cheap assets on the way. The Government’s resumed privatisation programme beginning with its remaining stake in Lloyds Bank might fit this description. But this in turn would cause further structural outflows from the UK economy as the yield on those cheaply-purchased assets flows overseas.

Sharp currency devaluations of this kind effectively reduce the international purchasing power of all income denominated in the domestic currency, in this case pounds. As a result, there will be improvement in the current account and trade balances, as imports become too expensive, some exports rise and the value of the yield on overseas assets increases when converted into pounds.

But this is in effect an enforced ‘improvement’. In popular phraseology, an economy living beyond its means has been forced to tighten its belt. Net domestic savings are negative, and overseas investors can choose not to lend to the UK economy. The occasion of this is the outcome of the Brexit vote and the Tory leadership’s determination to pursue ‘hard Brexit’.

It should be absolutely clear now to all except the wilfully ignorant that the current crisis actually impoverishes the overwhelming majority. All of these are Brexit effects, even before Brexit happens. The Tory party conference signalled that the priority would be anti-immigration, not pro-growth through the Single Market. Blocking access to the Single Market and attempting to lower immigration will both have the effect of lowering living standards further, even when the pound eventually finds a floor.

The alternative is equally clear. The UK should not leave the Single Market and should embrace its essential component Freedom of Movement as both are decisive for future prosperity. Logically, it would be foolish then to leave the EU which simply means having no influence or vote in future developments and would probably entail a sharply increased Budget contribution. Brexit is making us poorer.

Recent Comments