By John Ross

- The determinants of US economic growth in the medium/long term,

- The short-term position of the US economy in the current business cycle

Analysing these factors, the impact of the Trump tax cut on the US economy is clear:

- In the short term the US economy is recovering in its current business cycle from its extremely bad economic performance in 2016, of only 1.5% growth, and the Trump tax cut is likely to boost this upswing

- The tax cut will increase the US budget deficit, and therefore reduce the level of total US savings, thereby reducing US medium/long term growth – unless the US embarks on large scale foreign borrowing, which would directly contradict Trump’s aim of reducing the US balance of payments deficit.

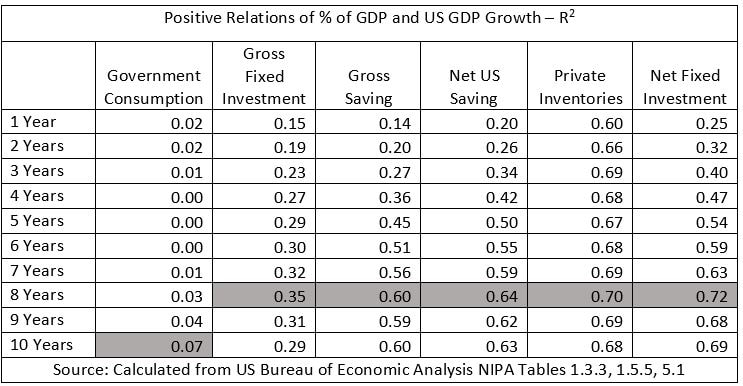

- in the short term no single fundamental structural factor, except accumulation of inventories, is strongly correlated with US economic growth – and inventory accumulation is a passive factor merely reflecting the acceleration and deceleration of US growth. Leaving aside inventories, over a 1-year period the strongest correlation of a structural factor in US GDP with US growth is the percentage of net investment in US GDP, but this only accounts for 25% of US growth in a one-year period – a weak correlation. In summary, in the purely short term numerous factors – the situation in the business cycle, international trade, even the weather – can significantly affect US growth.

- However, in the medium/long term there is an extremely strong correlation between structural elements of US GDP and US growth – the strongest positive correlations are shown shaded in grey in Table 1. The strongest correlation can be seen to be that between the percentage of US net fixed investment in the US economy, i.e. gross investment minus capital depreciation, with US GDP growth. This correlation accounts for the majority, 54%, of US growth over a five-year period and over a seven-year period US this correlation accounts for 72% of US growth – an extremely strong correlation.

The short-term position of the US business cycle

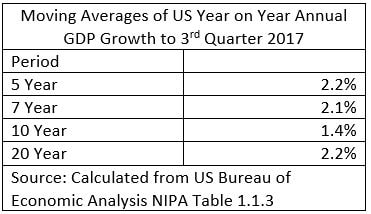

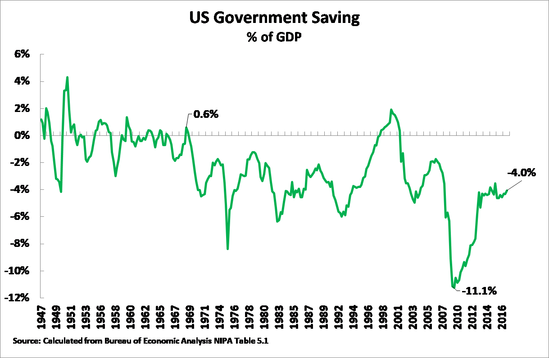

Analysing first short-term trends in the US economy this is greatly simplified by the fact that US medium/long term growth rate is among the world’s most predictable. Table 1 shows that over a 5-year period US annual average growth is 2.2%, over a 7-year period 2.1%, and over a 20-year period 2.2%. Only a 10-year period shows significantly different growth, at 1.4%, and this is simply a statistical effect of the huge impact of the international financial crisis of 2008. Given all these measures coincide therefore, annual average US GDP growth over the medium/long term may be taken as slightly above 2%. Given this stable medium/long term growth rate short term US business cycle trends simply show oscillations above and below this medium/long term average.

Table 2

Turning to the present situation of short-term shifts in the US business cycle, Figure 1 confirms that US economic growth in 2016 was extremely slow – only 1.5% for the year as a whole and falling to 1.2% in the second quarter. Given that the US growth rate in 2016 was substantially below its medium/long term average of slightly above 2%, a recovery of US growth was to be expected in 2017 for purely statistical reasons. This has duly occurred, with US year on year growth in the 3rd quarter of 2017 being 2.3% – marginally above the long-term US average.

The Trump tax cut is therefore being injected into an economy which is already recovering from its cyclical downturn in 2016. As the Trump tax cut is not accompanied by any equivalent reduction in US government spending it will therefore significantly increase the US budget deficit – estimates of the final effect of this are that the US budget deficit will increase by at least $1 trillion. A tax reduction which increases the budget deficit, that is which increases US government borrowing, may well increase a short-term recovery which is already occurring.

However, this increased budget deficit, other things being equal, will reduce US total savings – i.e. the sum of household, company and government savings. In the purely short term this fall in the US savings rate will not reduce US growth because, as was already shown, in the short term, i.e. one or two years, net saving and net investment are not closely correlated with US economic growth. Therefore, in the short term, the effect of extra spending arising from increased government borrowing, i.e. extra money flowing to corporations and consumers, may well lead to extra spending boosting already recovering US growth. For this reason, as already noted, in the short term, in 2018, the combination of the cyclical recovery and tax cuts is likely to lead to increase ‘short term gain’.

Figure 1

The medium/long term

However, in the medium/long term, as already noted, key structural features of the US economy, in particular net fixed investment, are extremely highly correlated with US growth. This, therefore, means that over the medium/long term analysing the trend in US net fixed investment gives an extremely clear guide to US economic growth performance.

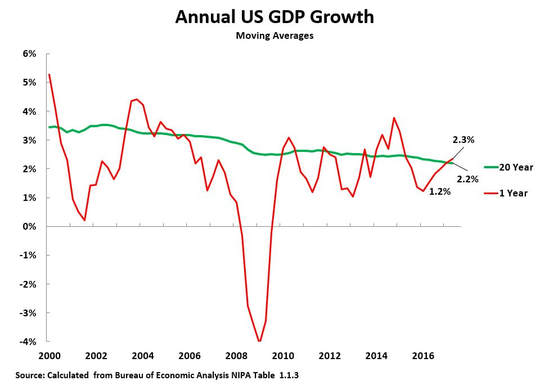

Necessarily the effect of a greater US budget deficit is to reduce US total savings – other things being equal. As Figure 2 shows the US already passed into almost permanent US budget deficit and government borrowing from the late 1960s onwards – with only a short period of budget surpluses under Clinton. By 2017, although it had recovered from the depths of the international financial crisis, US government borrowing was still 4.0% of GDP even before the Trump tax cut kicks in.

Figure 2

The household and company sectors

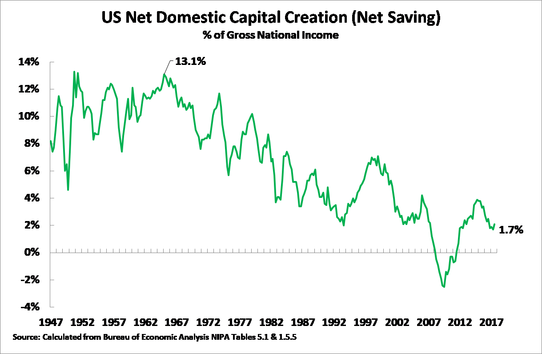

In theory, as US total saving is the sum of government, household and company saving, increases in US household and/or company savings could offset a fall in total US saving caused by an increased budget deficit – for example theoretically companies and households benefitting from the tax cut would save their extra income. However, Figure 3 shows, however, that no increase in these other potential sources of US savings was in practice sufficient to overcome the effect of increased US government borrowing resulting from US Federal budget deficits. The result of substantially increased US government borrowing, not offset by trends in the household or company sectors, was therefore to produce a sustained fall in US total savings – that is in US capital creation. US net savings, which had been 13.1% of US Gross National Income (GNI) in the late 1960s, by 2017 had fallen to 1.7% of GNI.

Figure 3

Saving and investment

Turning to the relation between US savings/capital creation and the key chief structural determinant of US economic growth, net fixed investment, it should be recalled that total investment is necessarily equal to total savings. Investment may, however, be financed by either US sources or by borrowing from abroad. Therefore, a reduction in US savings, caused by an increase in the budget deficit due to the tax cuts, necessarily means that US total investment must fall unless an equal foreign source of savings can be found.

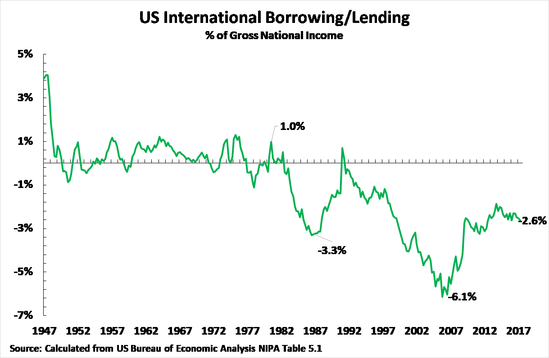

US presidents from Reagan to Obama were indeed prepared to use foreign borrowing to offset the decline in US savings – as Figure 4 shows. In the 3rd quarter of 1979, shortly before Regan came to office, the US was actually a net international lender of 1.0% of GNI. However, under Reagan the US embarked on massive international borrowing, this reaching a peak of 3.3% of GNI during his presidency. After a brief decline under George H W Bush, US foreign borrowing then expanded further under Clinton and George W Bush – reaching a peak of 6.1% of GNI in 2005. The shock of the international financial crisis then forced a reduction in US international borrowing, but it still stood at 2.6% of GNI in 2017.

Figure 4

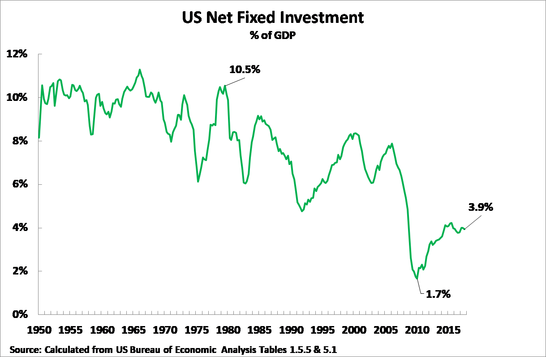

Nevertheless. despite this very large increase in US foreign borrowing Figure 5 shows that this insufficient to entirely offset the decline in US savings and maintain the previous US level of net fixed investment. US net fixed investment fell from 10.5% of GDP in 1978, shortly before Reagan came to office, to a low of 1.7% of GDP in 2010 immediately following the onset of the international financial crisis. US net fixed investment has since recovered to 3.9% of GDP but this remains far below its previous peak level.

Given the extremely strong correlation between US net fixed investment and US economic growth which was already analysed this sharp fall of US net fixed investment necessarily greatly reduces US economic growth.

Figure 5

The slowdown in US growth

Given the close correlation of US net fixed investment with the US growth rate, the necessary result of this sharp fall in US net fixed investment was therefore also a progressive slowdown in the US economy shown in Figure 6.

Taking a 20-year moving average, to eliminate any short-term effects of business cycles, US annual average economic growth has fallen from 4.4% in 1969, to 4.1% in 1978, to 3.5% in 2003, to 2.2% in 2017. The extremely close correlation of the percentage of US net fixed investment in GDP with the US medium/long term growth rates already analysed means that the Trump administration cannot significantly accelerate US economic growth without increasing the percentage of net fixed investment in US GDP.

Figure 6

The choices facing Trump

The fundamental determinants of US economic growth therefore clearly show the choices facing the Trump administration which result from the tax cut.

By carrying out a tax cut unaccompanied by any government expenditure reductions the Trump administrations is lowering the level of US domestic savings. This in turn necessarily means a reduction in US investment unless an alternative source of savings can be found.

As previously analysed previous US presidents from Reagan to Obama partially offset this decline in US savings by large scale foreign borrowing. But this large scale foreign borrowing necessarily has consequences for the US balance of payments and therefore for Trump’s pledge to reduce the US trade deficit.

- The current account of every country’s balance of payments is necessarily equal to the capital account of the balance of payments with the sign reversed – i.e. an increase in foreign borrowing must necessarily be accompanied by an exactly equivalent worsening of the current account balance of payments. Whereas previous US Presidents were prepared to accept a deterioration in the US balance of trade as the necessary price to pay for large scale foreign borrowing Trump made it a central pledge to reduce the US trade deficit – the chief component of the US balance of payments deficit. But it is arithmetically impossible for there to be an increase in US foreign borrowing without there being a worsening in the US balance of payments deficit – that is, in practice, without there being a worsening of the US trade deficit. The Trump administration is therefore faced with only one of two choices:

- If Trump sticks to the target of reducing the US trade deficit then the US cannot undertake significantly increased foreign borrowing, net fixed investment will therefore remain low, and US economic growth cannot significantly increase in the medium/long term.

If the US increases foreign borrowing, in order to increase the level of US investment, then this will necessarily mean an increase in the US balance of payments deficit – and therefore the Trump administration will be forced to abandon its central pledge of reducing the US trade deficit.

Contradictions of Trump’s policy

It is therefore clear that by its tax cut the Trump administration therefore places itself in an internally contradictory position in which it is impossible to simultaneously meet two of its stated goals:

- If the US does not increase foreign borrowing it cannot increase its level of fixed investment and therefore the US cannot significantly increase its growth rate – which was one of Trump’s key campaign pledges.

- If the US does significantly increase foreign borrowing, in order to increase its level of fixed investment and therefore increase its medium/long term growth rate, the Trump administration cannot achieve its goal of reducing the US balance of payments deficit – on the contrary the US balance of payments deficit will increase.

If it should be argued that the Trump administration can find a way out of this contradiction by, for example, increasing the level of Innovation in the US economy this, unfortunately, rests on a misunderstanding. First, the close correlation between US net fixed investment and US economic growth shows that other factors are not powerful enough to compensate for a lack of net fixed investment. Second, the factual data shows that while a combination of innovation and fixed investment is extremely powerful in raising US productivity and growth, innovation unaccompanied by fixed investment does not significantly raise US productivity – for a detailed analysis of the US factual data see “Reality & myth of the US ‘internet revolution’”

Other analyses

While the above analysis is made in terms of analysing the fundamental determinants of US growth it is also worth considering other analyses.

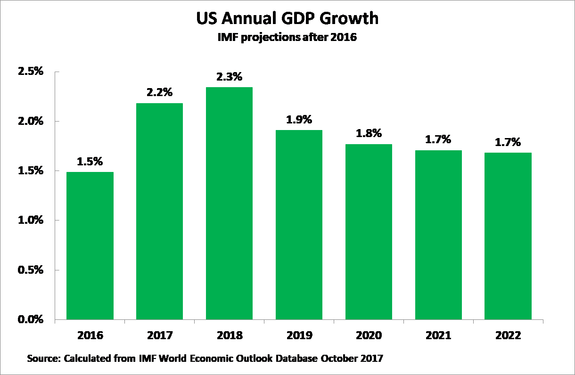

The IMF arrives at a fundamentally similar analysis to the above in its latest international projections – predicting a short-term increase in US growth in 2017-2018 but without any medium/long term increase in the US growth rate. Figure 7 shows more precisely that the IMF projects US 2.2% GDP growth in 2017, and 2.3% in 2018, before a decline to 1.9% in 2019, 1.8% in 2020, and 1.7% in 2021 and 2022. Overall the IMF projects annual average US growth in 2016-2022 of 1.9% – which is actually marginally below the average annual medium/long term US growth rate of slightly above 2%. Given the stability of US medium/long term growth, therefore, while the present author would agree with the IMF’s projected general pattern for the US economy, i.e. higher growth in 2017-2018 followed by a slowdown, he considers that US growth will possibly be slightly higher than the 1.9% annual average indicated by the IMF.

Gavyn Davies, former chief economist of Goldman Sachs, who runs one of the world’s most sophisticated ‘now casting models’, similarly concludes that while the pattern of faster US growth in 2017-2018 followed by slowdown is correct he predicts average US growth remaining just above 2%.

Figure 7

Lawrence Summers former US Treasury secretary has the same analysis. He characterises the increase in US growth in 2017-2018 as a ‘sugar high’ – the equivalent of the purely temporary short-term boost in human energy caused by taking a large dose of sugar. His analysis, given the self-explanatory title the: ‘US economy faces a painful comedown from its “sugar high”’ is that: ‘The tax-cut legislation now in committee on Capitol Hill exacerbates every important problem it claims to address, most importantly by leaving the federal government with an entirely inadequate revenue base. The bipartisan Simpson-Bowles budget commission concluded that the federal government needed a revenue base equal to 21 per cent of gross domestic product. In contrast, the tax cut legislation now under consideration would leave the federal government with a revenue basis of 17 per cent of GDP — a difference that works out to $1tn a year within the budget window.

‘This will further starve already inadequate levels of public investment in infrastructure, human capital and science. It will probably mean further cuts in safety net programmes, causing more people to fall behind. And because it will also mean higher deficits and capital costs, it will probably crowd out as much private investment as it stimulates.’

Politics

Finally, while the focus of this article is the economic prospects for the US, it is worth noting certain key US domestic and geopolitical trends which follow from this.

Under normal circumstances it would be expected that the relatively more rapid growth of the US economy to be expected in 2017-2018 would lead to favourable approval ratings for a US President. However, in addition to other purely political factors, opinion polls in the US show strong popular disapproval of the proposed tax cuts due to their being considered to be particularly favourable to the rich – polls show up to 58% of the US population disapproving of the tax proposals with only 37% approval. Overall a survey of US opinion polls on 16 December found 58% of US voters disapproving of Trump’s record as President and only 36% approving. It remains to be seen if the economic recovery likely to continue in 2018 will increase President Trump’s approval rating before the fact that the US medium/long term growth rate has not accelerated becomes clear. However, it is clear that a situation of continuing low US medium/long term growth will continue the present situation of instability in US domestic politics.

The reduction of the US savings level due to the increased budget deficit due to the tax cuts also has geopolitical implications. If the Trump administration turns to large scale foreign borrowing to try to increase US investment levels, and therefore accelerate growth, this will necessarily lead to a larger trade deficit. As this would clearly be contrary to one of Trump’s central campaign pledges it will lead to temptations to blame other countries for what are in fact difficulties created by the consequences of the tax cut – China may be a target of this. If, however, the US does not turn to foreign borrowing to boost investment and growth levels then US economic growth will not increase – which may also lead to seeking foreign scapegoats. In summary, the fact that the tax cut will not produce a significant acceleration in US growth, other than in the purely short term recovery in 2017-2018, may increase the temptation of the US to inaccurately blame other countries for what are in fact self-created economic problems exacerbated by the increase in the budget deficit.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the consequences of the US tax cut are therefore clear. They may be easily understood both in terms of the economic fundamentals considered and by those of other analysts including the IMF. The tax cut, by increasing the US budget deficit, will produce a ‘short term gain and long-term pain’, a ‘sugar high’ to use the term of Lawrence Summers. It will further boost a US recovery which is already taking place for statistical reasons in 2017-2018 but at the expense of undermining the US savings level and therefore the ability of the US economy to finance the investment which the data shows to be crucial for any significant increase in the US growth rate.

China’s economic policy, and that of other countries, must therefore be prepared both for the ‘short term gain’ of the US tax cut of 2017-2018 and for the ‘long term pain’, that is the low average US growth rate, that will be caused by the increase in the US budget deficit.

* * *

This article previously was published at Learning from China and originally appeared in Chinese at Sina Finance Opinion Leaders.

Recent Comments