By John Ross

‘People centred development’, including special emphasis on ‘green growth,’ was a central theme of this year’s annual China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) – its legislative body. The focus of the NPC, together with the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) which is held simultaneously, is always primarily domestic. However, China’s domestic agenda necessarily impacts on its international relations. Such international impact, in turn, reciprocally affects China itself – it is important for China that other countries do not pursue protectionism, that other countries pursue policies congruent with China’s in problems that can only be solved internationally etc.

Key policies at this year’s ‘two sessions’ will particularly have a major international impact due to the current international situation – which is seeing a slowdown in the Western economies, increasing concern within Western countries about poverty and social inequality, and increasing international anxiety and public agitation about climate change. China’s economic growth, its policies on poverty, and the policies adopted by China on the environment in general and climate change in particular will therefore have international impact. This correspond to a reality that China, in correlation with its growth target, and its poverty reduction, has set internationally leading targets for dealing with climate change and environmental issues. In this framework, this article, therefore, analyses this interrelation between China’s domestic priorities and international trends.

To avoid the suggestion of using sources excessively favourable to China all economic data used here, unless otherwise stated, is not taken from China but from the IMF. As the data for 2019 are projections if the differences they showed between China and other countries were small no great reliance could be based on such figures. However, as will be seen, the differences are not small, but the outperformance of China compared to the Western economies is extremely large – therefore, during 2019 small variations of economic performance from the IMFs projections will not affect the fundamental situation. For reasons analysed in my book Don’t Misunderstand China’s Economy, while in the past IMF projections for the Western economies have been too optimistic the current ones by the IMF are in general realistic – with one key exception noted below.

China’s growth rate

China set its economic growth target for 2019 at 6.0%-6.5%. To understand the global impact of this it is important to give an international comparison for the word’s three largest economies – the US, China and EU. China is expected to grow this year approximately two and a half times as fast as the US and more than three times as fast as the EU.

China’s performance is of particular significance as it will be set against the background of an overall slowdown of the Western economies. The IMF in its latest forecast in January projects that growth in the advanced Western economies as a whole will fall from 2.3% in 2018 to 2.0% in 2019, in the US it will decline from 2.9% to 2.5%, and in the Eurozone from 1.8% to 1.6%. Even if the IMF’s projection of China’s growth, of 6.2% in 2019 were accurate, and that is towards the bottom end of the government’s target range, this means the IMF projects that not only will China be growing two and a half times as fast as the US but the economic slowdown in the US will be more severe in relative terms than in China. Compared to this year the US economy would slow from 2.9% to 2.5%, or by 14% of the previous figure, while China would slow from 6.6% to 6.2%, that is by only 6% from the previous figure.

China’s growth target

These comparative international trends can be seen even more clearly if they are considered in per capita terms. China’s population growth is slower than other major economies – China’s population grew in 2018 by 0.5% compared to 0.7% in the US and 1.3% in India. Therefore, a part of US and Indian total GDP growth, compared to China, is simply due to more rapid population growth. However, the increase in the wellbeing of any country’s population is determined not by total GDP but by per capita GDP.

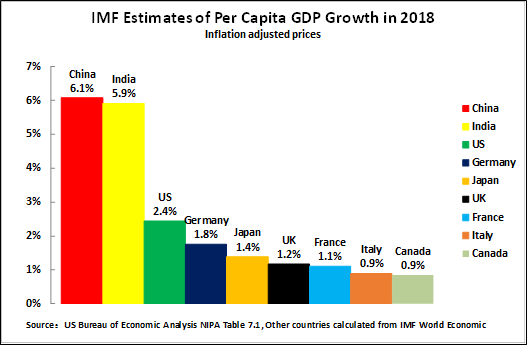

Even if India’s official growth figures are accepted, which many experts even in India would not do, then in per capita GDP terms, as shown in Figure 1, China’s growth in 2018 was the fastest for any major economy – 6.1% compared to 5.9% in India and, considering Western economies, far faster than the 2.4% in the US, 1.8% in Germany, and 1.4% in Japan.

Figure 1

Making a comparison to major Western economies for 2019, the IMF projects China’s per capita GDP growth will be 5.7% compared to 1.9% in the US and EU, 1.8% in Germany, and 1.3% in Japan. That is:

-

- China’s per capita GDP growth will be three times as fast as the US.

-

- China’s per capita GDP growth will be three times as fast as the EU, and more than three times as fast as Germany

-

- China’s per capita GDP growth will be more than four times as fast as Japan.

To summarise, the conclusions of this are evident:

-

- First, even at the level of total GDP growth, the attempt by sections of the Western media to claim that China’s economy is in ‘deep crisis’ is pure nonsense – China’s economy will grow two and a half times as fast as the US and three times as fast at the EU.

-

- Second, the contrast in per capital terms is even greater – China will grow three times as fast as the US or EU.

-

- Third, as the Western media is at present full of false propaganda about ‘severe slowing’ and ‘deep crisis’ in China’s economy, the slowing of the Western economies, which is already receiving increasing attention, will provide a very favourable opportunity to show once again the falsity of claims about China

Finally, from the point of view of explaining this situation internationally, it is likely to be very useful, and objectively correct, for China to emphasise per capita trends as well as total GDP trends – as the fact that China’s population growth is significantly slower than other major economies conceals some of the real international contrasts in development.

Contributions to world growth

From the viewpoint of the standard of living of China’s population per capita development is the most important. However, from the viewpoint of other countries’ trade and investment, and therefore their objective interest in interaction with China, it is the total size of China’s economy and growth which is decisive. In order to assess the international impact of the NPC decisions, therefore, it is necessary to analyse the projected contribution of China to world growth in comparison to other countries.

Calculated in PPP terms, which reflects the real increase in the number of sales of goods and services, the IMF projects that China will account for 27.2% of world growth in 2019 compared to 12.3% for the US and 11.8% for the EU. That is, China’s contribution to world growth in these terms will be more than twice that of the US and EU – or put in other terms, China’s contribution will be as large as the US and EU combined. This is, of course, vital for companies aiming to sell into China’s market.

Calculations in current exchange rates by the IMF are unclear as, for reasons which it does not justify, the IMF makes the extremely strange assumption for 2019 that the RMB will undergo a significant devaluation against the dollar. To be precise, the IMF projects that while China’s GDP in constant price terms will increase by 6.2%, and in current RMB prices will increase by 8.6%, in current dollar terms China’s GDP will only increase by 5.3% – which could only be explained by a significant RMB devaluation. This exchange rate projection is neither in line with current trends nor with reports of an exchange rate agreement between China and the US in current trade negotiations. However, this appears to be an anomaly for 2019 in that the IMF estimates that over the whole five-year period 2018-2023 at current exchange rates China will account for 26% of world growth and the US and the EU will each account for 17%. This is over the next period as whole China’s contribution to world growth at current exchange rates will be more than 50% greater than either the US or EU.

In summary, in terms of sales over the next period, China’s economy will grow more than twice as fast as the US or EU and even at current exchange rates it will grow more than 50% more rapidly – providing a firm basis on which to attract other economies to increasing economic interaction with China.

Total GDP growth is not the target

But while it is significant to note projected growth rates, China has rightly emphasised that GDP growth cannot by itself be the target of policy. The correct goal is ‘people centred development’, that is the improvement of the overall living conditions of its people – including in relation to problems that by their nature can only be solved internationally.

China has long led the way globally in speed of increase of living standards, which for the last 40 years have been by far the fastest in any major economy, and in poverty reduction – since 1978 China has accounted for almost three quarters global fall in the number of those living in World Bank defined poverty. China’s pledge to entirely eliminate absolute poverty by 2020, repeated at this year’s NPC, remains an inspiring goal for all humanity.

These issues also illustrate the link between economic development and human well-being – growth of per capita GDP is not just a question of ‘concrete and steel’, i.e. physical production. Economists know that average life expectancy is the best indicator of overall human living conditions as it sums up in a single figure all positive (reduction of poverty, education, good health care, environmental protection) and negative (poverty, bad health care, lack of education, environmental damage) trends. Internationally more than 70% of differences in life expectancy between countries are explained by differences in per capita GDP.

Regarding China its life expectancy has continued to increase steadily – an indicator of its overall improving average social conditions as well as the success in poverty reduction. But it is therefore an extremely disturbing trend that in the US life expectancy has now been falling for three years and in the UK life expectancy has also started to decline – such a situation has not existed in these countries for decades. This clearly can only reflect a deteriorating social situation which, in turn, underlies heightened social and political conflict in these countries – the political turmoil continuing to surround the Trump administration, the economically irrational Brexit decision in the UK etc.

Some people in the West now argue that changes in distribution of income within advanced economies, particularly the US and UK, where this is extremely unequal, could ensure the maximum social progress even without economic growth. But whatever position is taken on this regarding the West, where it is becoming a hot debate in some circles, in developing countries such as China this is impossible. Continued development of per capita GDP, in the framework of ‘people centred development’, is therefore vital for the well being of China’s population and its growth target maintains this.

China’s methods of poverty reduction are of direct concern in developing countries. But even in advanced economies, with a higher per capita GDP, the difference of methods used by China at different stages of development for eliminating poverty are of interest – and likely to win widespread support.

To lift more than 800 million people out of World Bank defined poverty, as China did after 1978, China necessarily relied on overall economic growth – no targeted measures would have been powerful enough. But even with economic growth the last few tens of millions of people living in absolute poverty in China could be left there – because they are in very inaccessible parts of the country or for other reasons. Therefore, for final success in eliminating poverty, China has to rely on targeted measures – which require conscious directed state policy as set out by the NPC. In both the US and UK, which rely overwhelmingly on the ‘invisible hand’ in the economy, key measures of poverty have actually increased in the last period.

China’s achievements in poverty reduction are so overwhelming ahead of the rest of the world that this should be a central part of its public image and presentation – in the West even anti-China politicians are forced to praise China for its unparalleled success in poverty reduction.

Ecological civilization

But in addition to immediate struggles to raising living standards, to provide social protection, to extend health care, and to eliminate poverty, in the present world ‘people centred development’ must also centrally include the fight against environmental degradation and against climate change. The latter, in particular, is a literally deadly threat to the whole future of humanity. These goals require building an ‘ecological civilization’, as President Xi Jinping has put it.

The effects of global climate change are already clear. The world is already seeing record-breaking temperatures, extreme heatwaves, storms, floods, and wildfires leaving a trail of death and devastation – and this situation will become progressively worse as global temperatures rise. As the UN’s Antonio Guterres has said, scientists have warned about global warming for decades, but ‘far too many leaders have refused to listen [and] far too few have acted with the vision that science demands.’

This extremely dangerous threat to the whole of humanity is therefore being increasingly reflected in generating social and political movements internationally. In the US recognition of the danger of climate change is extremely widespread with those concerned on this issue ranging from multi-billionaires such as former Mayor of New York Michael Bloomberg, through entire US states such as California, to the ‘Green New Deal’ put forward by many political figures which calls for concerted action on climate change and commands widespread popular support. Young people, who will face the worst consequences of climate change during their lifetimes, have started to become increasingly active – with in Europe an international movement of school strikes against climate change. Leaders in Pacific Islands term have termed this threat a literal genocide – their countries will physically disappear beneath rising sea levels if action is not taken.

The effective fight against climate change requires both correct policies and huge technological and industrial capacities and the objective situation is that China alone possesses both. The emphasis on ‘ecological civilization’ at the NPC is therefore particularly important given that, unfortunately, the Trump administrations in the US is continuing to undermine the Paris Climate Agreement and has made clear that the US will withdraw from it when the rules allow President Trump to do so in 2020.

The NPC decisions go in exactly the opposite direction to the regrettable US deeply irresponsible policies. They are therefore both in the interests of the Chinese people and in line with majority, and an increasing majority, of international opinion. More specifically, in a key target the work report projects China’s energy consumption per unit of GDP to continue to fall by about 3% in 2019. Regarding key forms of environmental pollution sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions will drop by 3%, and the concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) will continue to decline in key areas. This year’s chemical oxygen demand and ammonia nitrogen emissions will drop by 2%.

Progress made by China in tackling pollution in the last years is also regarded internationally as striking. A few years ago, as was recognised not only in China but internationally, major Chinese cities had very serious problems of smog and pollution – with Beijing being the most widely cited case internationally. But in 2018, as even Ian Bremmer, head of the Eurasia Group, the leading Western ‘risk evaluation’ company, and a severe critic of China noted, Beijing is no longer even in the top 100 most polluted cities in developing countries – regrettably seven out of the ten most polluted cities are now in India. This is not at all to underestimate how much still much remains to be done to fight against climate change and tackle pollution, but China is making a decisive turn to environmentally favourable policies while other countries, notably the US, are retreating from them. Furthermore, China is having measurable success. This will necessarily have an impact on international opinion.

Convergence with international forces

On the issue of climate change, therefore, China’s policies are objectively aligned with an extremely wide range of forces internationally, ranging from billionaires to school children, on what an increasing number of people in the West consider the most important issue facing humanity. This creates important possibilities for China to create alliances with very broad groups – even some who are normally hostile to China but who consider such differences less important than dealing with what they see as a fundamental threat to humanity.

The context for this is that the 2020 international climate talks are supposed to agree new national commitments consistent with constraining global temperature rise ‘well below two degrees’. This is given greater emphasis by the recent conclusion of the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) that the only science-based target to tackle the climate crisis is to constrain global average temperature rise below 1.5 degrees above the pre-industrial average – although this is not yet accepted officially as an international target.

Overall, while China’ comprehensive national strength is rising it cannot yet play an all-round leading role on international issues – views such as that China’s comprehensive national strength is already equal to the US are incorrect, and views such as that the dollar can be replaced as the leading international currency in any short/medium term period are also unrealistic. But as China’s comprehensive national strength increases it will be able to take a leading international role on certain issues. Climate change is one of them – most developing countries would welcome China playing such a role and it may be possible for China to come to an agreement with the EU, leaving the present administration in the US relatively isolated on this issue.

This trend directly coincides with increasing concern in the West about climate change and an increasingly open support for China’s policies in several fields related to this. Western experts note that China is already ahead of its target of reaching peak emissions by 2030 – recent Western estimates are that this will be achieved in 2025 or even slightly earlier. Interestingly the target date that would be required to meet a global target of 1.5 degrees is only slightly earlier – 2022.

To take specific areas, China is already by far the world leader in electric vehicles for public transport. Shenzhen is world’s first city to have a 100% electric bus fleet and this is extremely large – almost 16,000 vehicles. The next nine cities in the electric bus global top ten are also all in China and have thousands of vehicles. To show the scale of China’s lead, the next highest cities in the world after China are London and Santiago in Chile with roughly 200 each. China is also by far the world leader in urban cycle hire.

Similarly, the ‘C40 Cities – Climate Leadership Group’, which joins together 90 leading cities internationally, representing more than 650 million people and including one quarter of the global economy, asks all its cities to commit to all new buildings being zero carbon by 2030. China can technically achieve that.

There are numerous ‘hot’ issues to be considered in the coming international climate change discussions – – regarding which a strictly objective dialogue is crucial. For example, emissions from China’s own coal powered electricity generation is scarcely rising – it went up only one percent last year, but pro-China Western experts, who are overall strong supporters of the Belt and Road initiative, are worried about the effect of new coal power stations that are part of the Belt and Road initiative.

On the other hand, twenty years ago, under Clinton and Gore, the US forced the UN to adopt a method of measuring climate emissions that favours western countries – by measuring emissions at the point of production within a state boundary (so a country’s emissions are calculated from adding up pollution from power stations, vehicle emissions etc). A more accurate measure is to calculate based on what is consumed within a country and follow the emissions back down the supply chain (so looking at the materials that make up a washing machine and how they were produced, what it took to feed the pigs that are turned into bacon, the process of manufacturing clothes and how they are transported to the point of retail sale etc). The latter is more accurate in attributing real responsibility for emissions and climate change. The US’s measured emissions would rise by minimum of 20%, probably more, if such a consumption methodology was used – while China’s would fall substantially. This would of course be a good but radical change.

Serious negotiations therefore lie ahead in which both economic and environmental factors must be considered. But what is clear is that China already has the leading position among the largest states in dealing with climate change and this is increasingly recognised by other countries and international environmental organisations. This issue is not only vital for China itself but also vital for the whole world and for international perception of China.

China’s framework is, of course, its ‘national rejuvenation’. A ‘vanguard’ of clear-headed people in other countries can understand that China’s national rejuvenation is in their interests as well. But the mass of people judge things by whether they benefit from them – that is agreements must be ‘win-win’. This is a central part of Xi Jinping’s concept of a ‘common future for humanity’. China’s policies on its economic growth and climate change precisely create ‘win-win’ solutions for itself and other countries.

Conclusion

The need for ‘people centred growth’ adopted at the NPC, which centrally includes integrating economic growth with environmental concerns, flows from China’s own domestic needs. But it also provides a key basis for China’s international agreements – which in turn are significant for China’s own development. They are also a key part of China’s ‘soft power’. These policies have been adopted for implementation in China to correspond to China’s domestic development but, as shown, they also fit with current trends globally. It is therefore greatly to be hoped that China’s diplomacy and public relations will skilfully project these issues internationally.

This article was previously published on Learning from China and the Chinese language version of this article first appeared at Guancha.cn on 15 March 2019.

Recent Comments