By Tom O’Leary

Keir Starmer’s speech on A New Chapter for Britain was heralded as a breakthrough moment where he would simultaneously set out his vision for the economy and society while beginning to outline a wholly different economic policy. If that was its purpose, it failed miserably in every respect.

But the speech does have some value as it highlights some striking misconceptions that are unfortunately quite widely shared across the labour movement. These are important to deal with because they are disarming the movement in the current crisis.

Starmer’s policies

The concrete pledges in the Starmer speech are as listed below:

No £20 cut in Universal Credit

Funding for local authorities to prevent ‘huge rises in Council Tax’

No pay freeze for key workers

Extend business relief and the cut in VAT for hospitality and leisure

Loans for small business start-ups

And, ‘update and extend’ the furlough scheme

Though generally welcome, all of these are limited, short-term measures in response to a feature of the current crisis. They are not a vision for either a more prosperous or less unequal Britain over the medium term, or even a policy to reverse this crisis.

There is too some confusion over the plan to introduce a ‘British Recovery Bond to raise billions’, which is clearly aimed at private individuals by giving “millions of people a stake in Britain’s future”. It is wholly unclear how this would differ from existing National Savings Schemes, or how it would add much for investment, given the outstanding level of ordinary government debt is just under £2.5 trillion.

SEB has long argued for a substantial increase in government borrowing for investment. But this seems to fall way short of that.

Common fallacies across the labour movement

As insubstantial as the Starmer speech is, its paucity is indicative of a wider malaise across the labour movement. This can be encapsulated in large sections of the labour movement adopting and repeating the Tory slogan of, ‘Build Back Better’, which is the ‘Land Fit for Heroes’ of our era. The promise that there is no intention to deliver.

The idea that they are engaged in ‘deficit-financing growth’ is a myth exposed by their own Budget in 2020. Instead, leaving aside one-off measures to cope with the fall-out of their damaging Brexit, Budget 2020 showed cuts to total government spending over the medium-term.

The innovation was that there is a planned increase in government investment, rising from a pitiful 2% to an extremely modest level of 3% as a proportion (of exceptionally weak) GDP. Even before the wider economic effects of the pandemic were apparent, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast 10 years consecutive growth that never once reached an annual rate of 2%, which would be historically unprecedented – and which was largely a Brexit effect.

But the government also planned to reduce government spending overall, by cutting public services and public sector pay. So, far from deficit-financing growth, the outlook even before Covid-19 was that inducements to the private sector to invest would be paid for by workers and the poor. This is more like austerity-driven stagnation.

The scale of the crisis

Unfortunately, the OBR’s view of economic prospects is much closer to reality than the Build Back Better boosters of the Tory Party. In fact, the OBR could not know a year ago how the government was actually going to proceed with economic policy beyond its fiscal plans, so its own projections are also probably too optimistic in the short-to-medium term.

What the government has done is to launch a ferocious assault on working class and the poor, and has provided every encouragement to employers to do the same. Far from ‘better’, measures already enacted will make matters far worse for the overwhelming majority of the population unless they are resisted and reversed.

Starmer’s speech blithely ignores all of this. Yet this is the central issue that the labour movement must grasp unless it is to go down under an enormous defeat. To demonstrate that this is not hyperbole, the charts below illustrate the real trends in the economy, focusing on the labour market.

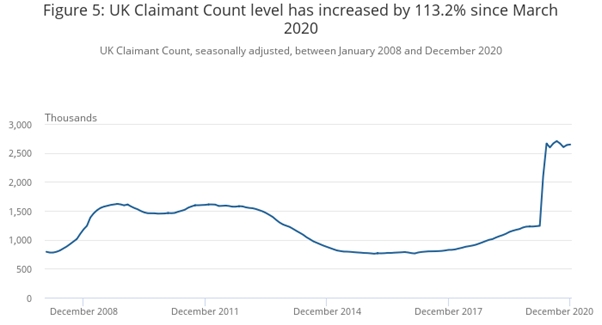

Since March 2020 the number of people claiming unemployment benefits has risen by 1.4 million, more than doubling in less than a year despite the furlough scheme.

Chart1.

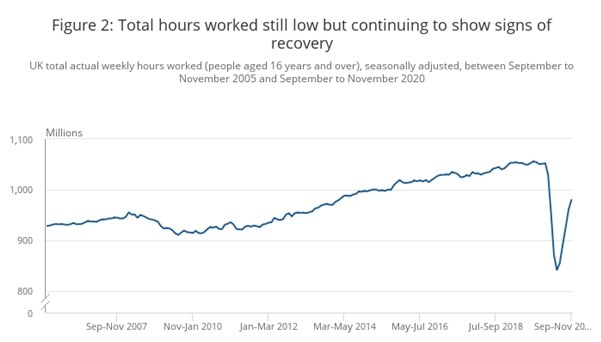

For those in work, hours have been slashed, down by 7% since the pandemic began.

Chart2. UK Total hours worked (millions per week)

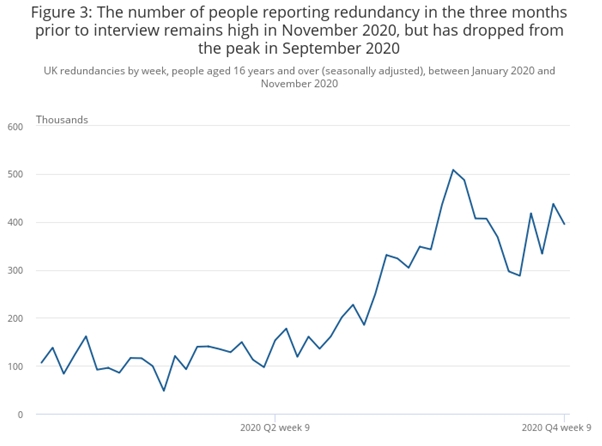

In addition, redundancies peaked at over half a million in the 3 months to September. But total redundancies since March 2020 have amounted to well over 1 million.

Chart 3. UK Redundancies, 3-month rolling data, thousands

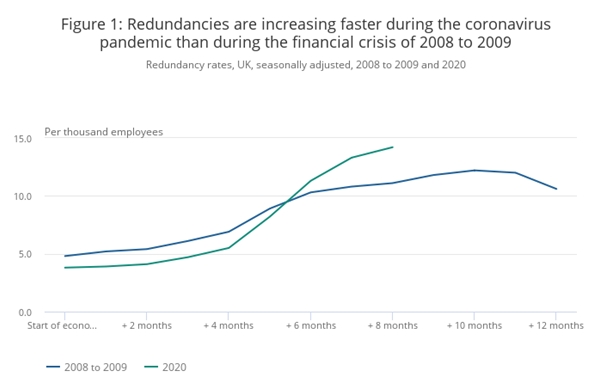

In its own analysis the office for National Statistics shows that the current rate of redundancies currently exceeds the rate after the financial crisis.

Chart4. UK Redundancy Rates Compared, the Pandemic Versus the Financial Crisis

Meanwhile, the reported rise in average annual pay is misleading. As already noted, payroll employee numbers have fallen sharply and these have been concentrated among the lower paid, which pushes the average for the remaining employees higher.

Taken together these trends amount to an all-round attack on the pay, hours and conditions of workers, especially lower-paid workers. They are underpinned by the rapid rise in unemployment, which both increases the available supply of labour and undermines union bargaining positions. In addition, the freeze on pay in the public sector (accounting for 5 million workers) is designed to place a cap on all workers pay.

The outlook is even more bleak. According to the Resolution Foundation 8% of all those currently in work either expect to lose their jobs or have been told they will lose their jobs. Even if only half of them are right, this would mean another 1.2 million unemployed.

Conclusion

It is this crisis that economic policy should seek to address, with strong public investment, job-creation and redistribution.

First though, it requires accepting the reality of the scale of the crisis. Secondly, it needs to be understood that these are the economic indicators behind the widespread ‘fire and rehire’ policies, a conscious effort by the employers and this government to increase the rate of exploitation. They are not a response to lockdown, still less a natural outcome of a pandemic. Thirdly, the ambition for economic policy must be commensurate with the scale of the attack that is being mounted. Otherwise, we are simply accepting defeat without a fight.

This is what Starmer neglects. The labour movement as a whole cannot afford to be so complacent.

Recent Comments