By Michael Burke

We are currently facing the most prolonged economic crisis in recent history, the most vicious attacks by a government determined to decimate living standards and clamp down even further on trade unions, and the biggest trade union resistance to that for decades. Naturally, each of these three is related.

The government has shown itself to be both intransigent and preparing for the long haul with renewed anti-union legislation. The labour movement is responding in kind and will need to be equally resolute and strategic.

There is no accident about the timing. Tories have long cherished the idea that there should be even greater curbs on trade union activity. But now we are in the middle of a huge strike wave and a prolonged economic crisis.

The anti-union laws already in place in this country are some of the most draconian in any advanced industrialised country. Research from ITUC, the international TUC, shows that this country is among the worst offenders in Europe when it comes to violating trade union rights.

The new additional minimum service level agreements to be imposed across large parts of the public sector are intended to ratchet these up. Notably, the legislation is not designed to have any impact on current disputes. The government clearly intends future fights.

The backdrop is that the British economy is experiencing a “stagflation” crisis, the combination of a stagnating economy and surging prices. In the most recent monthly data, the economy registered zero growth from a year ago, while consumer price inflation remains painfully high at over 10 per cent.

Worse, the current economic crisis is an extension of much longer trends, with no end in sight. Inflation will probably subside to some extent at some point but prices will not fall back. At the same time, British government subsidies and handouts to firms while cutting public spending and investment in real terms are a recipe for prolonged stagnation.

In response to the crisis, the government is trying to shift the burden of it onto the shoulders of workers and the poor. It has been intransigent on pay, interfered to block negotiations, in many cases refused to talk and is clamping down on trade union rights.

It has focused on the sectors the government directly or indirectly controls. It hopes that this will set a “going rate” across the economy well below inflation, for both the private and public sectors.

With this, the government hopes to both lower real wages across the board and keep them there by limiting the effectiveness of trade unions.

While the government is seeking longer-term solutions to the economic mess, so too the labour movement and its allies should examine alternative longer-term strategies, to keep the burden where it belongs, with big corporations, banks and landlords.

To some extent, this is a repetition of history. The inspiration for the current Tory policy stretches back to Margaret Thatcher. Then, as now, there was a string of legislation curbing the rights of workers to form unions or the rights of unions to organise their members for industrial action.

Thatcherism was also a response both to an economic crisis and a wave of trade union militancy which had resisted efforts to impose “pay restraint” which were designed to lower wages in real terms (after inflation).

Thatcherite ideologues claiming success for those policies ignore two key facts. The first is that Thatcherism benefitted from an extraordinary windfall of North Sea oil revenues that amounted to approximately 15 per cent of GDP during her time in office.

Secondly, taken as a whole, the three decades of Thatcherism and its legacy produced significantly lower growth than the three decades that preceded it. In the post-World War II period before Thatcherism, the British economy’s growth rate was about 3 per cent on average. Post-Thatcher it was less than two-thirds of that and has since slipped to below 1 per cent under austerity.

Yet the government is now doubling down on a policy which has failed.

The policy amounts to transferring incomes and wealth from poor to rich and from workers to big business. But the recent experience of the British economy is that this falling labour share of national income has also been accompanied by a private-sector investment strike.

The private sector does not feel compelled to invest if it is able simply to squeeze workers harder.

This is common across the G7 economies. But Britain is the worst example. The British economy lags behind even comparable countries which themselves have experienced a declining rate of investment.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from 1997 and 2017, the proportion of GDP directed towards fixed investment in Britain was the lowest in the OECD as a whole, at 16.7 per cent of GDP. The next lowest are Italy and Greece, both at 19.6 per cent of GDP.

This is a private-sector failure to invest in the means of production. It leads directly to an inability to increase production in any significant way. This in turn has produced economic stagnation.

It would be very difficult for any government to raise living standards and improve public services in these circumstances. But austerity deepens the crisis for the mass of the population while public services are in crisis. Take-home pay and welfare benefits have both been cut in real terms.

This chronic private-sector failure has now become acute. Therefore, the state must take the lead role in reviving the economy through investment while sharing incomes more equitably through redistribution.

The state has no compulsion to distribute returns to shareholders. It can raise its own level of investment and deliver the same effects as falsely promised on behalf of the private sector.

It can also borrow for investment as the private sector does, or should.

But public investment must also be restored. It has amounted to only 1 per cent of GDP for most of the last decade, compared to up to 5 per cent of GDP in the pre-Thatcherism period of much stronger growth.

A bold public investment programme would be a truly green and just transition in energy, transport and housing, with taxes on the banks and big firms to pay for the restoration of public services, a massive increase in publicly owned housing, and renationalised public services.

A key part of the revival of public services must be inflation-plus pay rises to recruit and retain workers. This should also apply to those sectors the government effectively controls, but where the private sector rakes off subsidised profits, such as rail, post and telecommunications.

In addition, existing and planned anti-union legislation should be scrapped, to allow organised workers to bargain collectively for decent settlements.

The government should also outlaw zero-hours contracts and other casualisation measures, and offer those on the minimum wage and benefits something like the pensioners’ triple-lock.

The fight-back against the government has begun and it is determined to block it. Everyone with an interest in opposing austerity and cuts to living standards should also oppose government anti-union legislation.

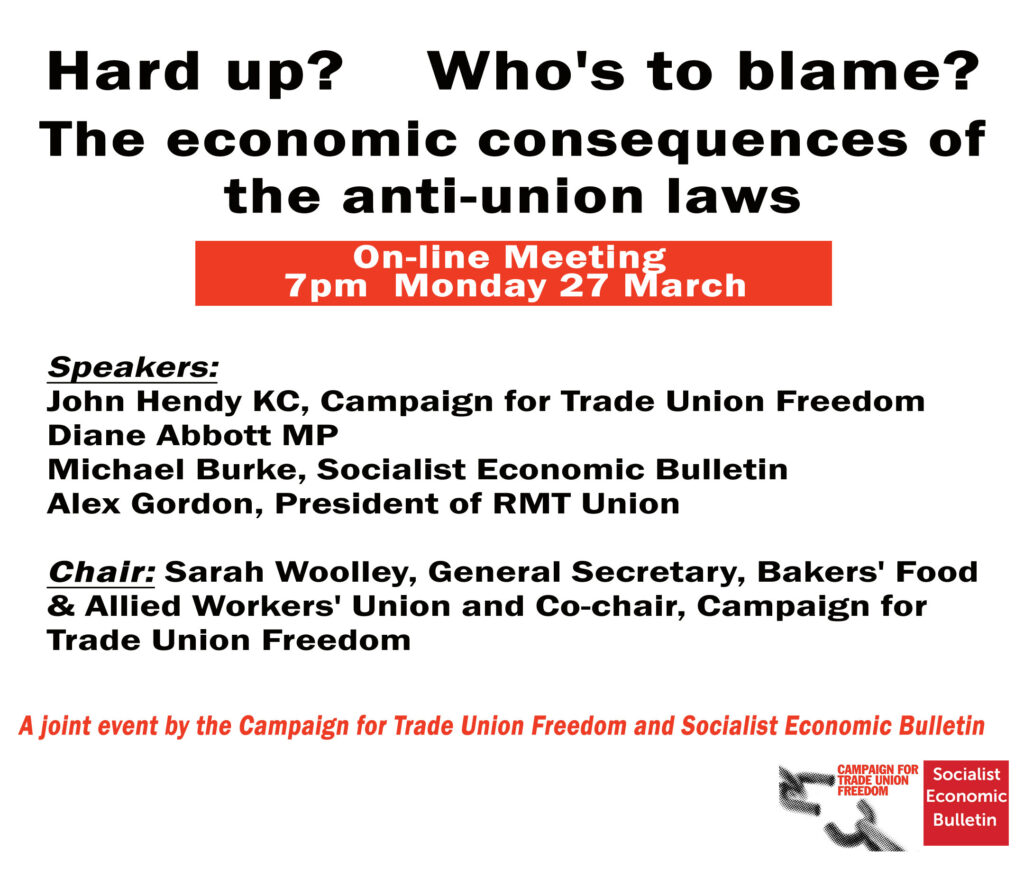

The Campaign for Trade Union Freedom and Socialist Economic Bulletin have jointly organised a meeting to develop the links between the anti-austerity struggle and the fight for union rights. Join us online on Monday March 27 at 7pm to find out more.

Register for your free place here.

The above article was originally published here by the Morning Star.

Recent Comments