By Michael Burke

The world economy as a whole is suffering a period of significant economic slowdown and surging prices. The effects of these trends are uneven. In general workers and the poor in the richest countries are getting poorer as real incomes fall. In many countries of the Global South the situation is much worse, with outright misery commonplace along with the growth in hunger.

The causes of the crisis have generally been obscured. A number of spurious explanations have been put forward as to the cause of the crisis; the war in Ukraine, ‘bottlenecks’, wage inflation, even bad weather.

The true cause of the crisis was the synchronised economic stimulation policies of the G7 countries, both monetary and fiscal policy, without any corresponding increase in Investment. Equally, as the G7 countries have largely been unwilling to unwind or reverse these policies the crisis has persisted for far longer than many had hoped or forecast. Inflation has generally remained persistently higher than forecast, and the policy response of higher interest rates will only exacerbate the slowdown without addressing the underlying cause of inflation.

Unless that policy mix in the G7 changes, prices will continue to rise at a destructive rate even as inflation slows and the world economy will remain sluggish or stagnant. Yet there is no sign of current policy being reversed.

Instead, there is a general trend, which began in the US to add protectionism to the toxic mix. This was marked by the introduction of the US’s ironically named ‘Inflation Reduction Act’, which is thoroughly protectionist. Other G7 countries and the EU as a whole are responding in kind. This is a recipe for deepening economic crisis, not alleviating it.

Exploding Myths

The myths about the causes of the crisis are now so well-established in both economic debate and popular discussion that it is necessary first to debunk them. Fortunately, this is a relatively easy task, by reference to the facts.

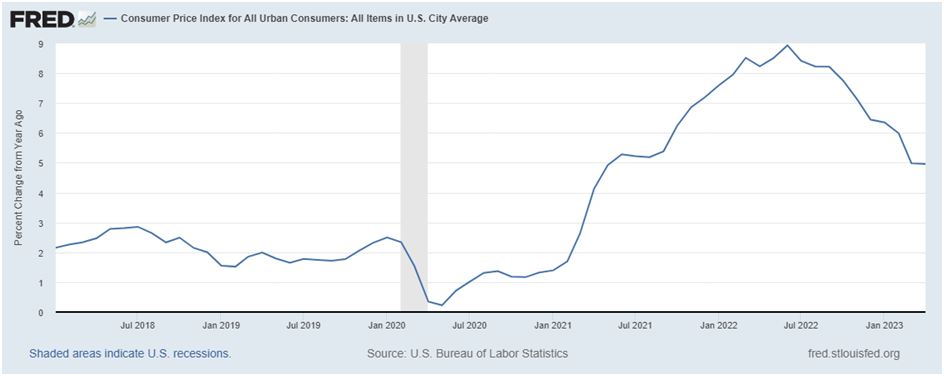

Chart 1. below shows the year-on-year growth rate of consumer prices (CPI) in the US economy. US CPI growth hit a low of 0.2% in May 2020 as the economy had slowed sharply following the failed attempts in curbing the Covid virus and lockdown. But once lockdown was ended and (as we shall see) economy policy changed, then US prices started to rise rapidly. By February 2022 CPI had reached 8%, and eventually peaked a few months later at 8.9%.

Chart 1. US Consumer Price Inflation (percentage change, year-on-year)

February 2022 is an important date in the mythology of the current crisis, because it was at the end of this month that Russian forces moved into Ukraine and began this phase of the military conflict. The logical problem with ascribing the surge in prices to the war, as most Western commentators have done over a prolonged period, is that the inflation wave began almost two years earlier, in May 2020 as the Chart shows.

In addition, the bulk of the rise of in prices took place before the war, from 0.2% to 8%. Finally, inflation has actually been subsiding for most of duration of the war, from June 2022 until now.

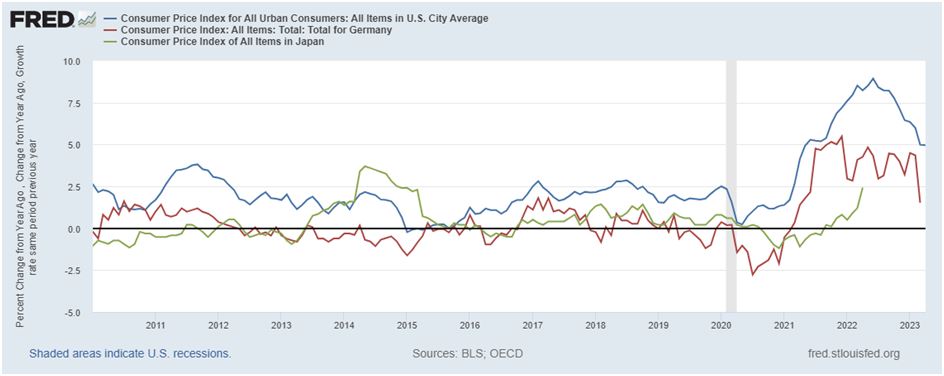

A similar pattern is identifiable in the other advanced industrialised economies, with some national variation, as shown in Chart 2 below. The rise in inflation was not caused by the war. So the claims by President Biden and other who have called it, ‘Putin’s gas price rise’, are simply to deflect responsibility.

At most, some prices of some important commodities received an initial push higher because of the war, but that effect has long subsided.

Chart 2. US Consumer Price Inflation (percentage change, year-on-year)

The rise in inflation was not caused by the war

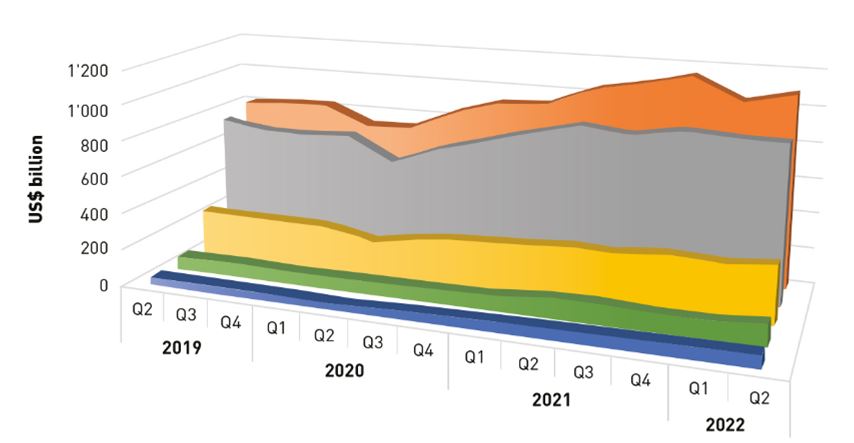

Another of the widespread false explanations offered is that there was a sharp rise in ‘bottlenecks’ that occurred during the lockdowns in the G7 countries and elsewhere. All manner of supply disruptions did take place during the lockdowns. But it is possible to discount genuine factors such as the difficulty of shipping finished goods, for example. An unwanted build-up of unsold finished goods would have the effect of lowering prices, as producers discounted prices to shift goods.

Conversely, if producers cannot easily access either basic commodities or intermediate goods (goods which require further manufacture before they become a finished good), then they will tend to bid up prices and so add to inflationary pressures.

Yet, according to data from the World Trade Organisation (WTO) the shortage of these inputs was both shallow and short-lived. Production bottlenecks did not cause the rise in global prices, as shown in the WTO chart reproduced below.

Chart 3. World Exports of Commodities and Intermediate Goods, quarterly, US$ trillions

Source: WTO

The remaining explanations advanced include the weather and wage inflation. It seems inevitable that climate change will cause large-scale and severe economic disruption. But the climate crisis is a continuous process and there are no specific weather patterns which would have caused such a sharp, global rise in prices. This is especially true as the major commodities initially leading prices higher were oil and gas. Climate change cannot explain the slow decline in inflation which is under way.

In contrast, there has been the rise in widespread labour shortages reported in many countries, and a genuine labour component of what can be described as ‘bottlenecks’. However, in the G7 countries which have led prices higher, there is no evidence of an effect on prices, particularly the price of labour.

Instead, what has taken effect is a large downward pressure on real wages in many of the G7 countries. This is inexplicable to those who argue that wages are set by the laws of ‘supply and demand’. If that were true shortages of labour would lead to higher wages. In reality, wages are set through the all-round struggle between classes. The policy pursued by the G7 governments is to lower real wages.

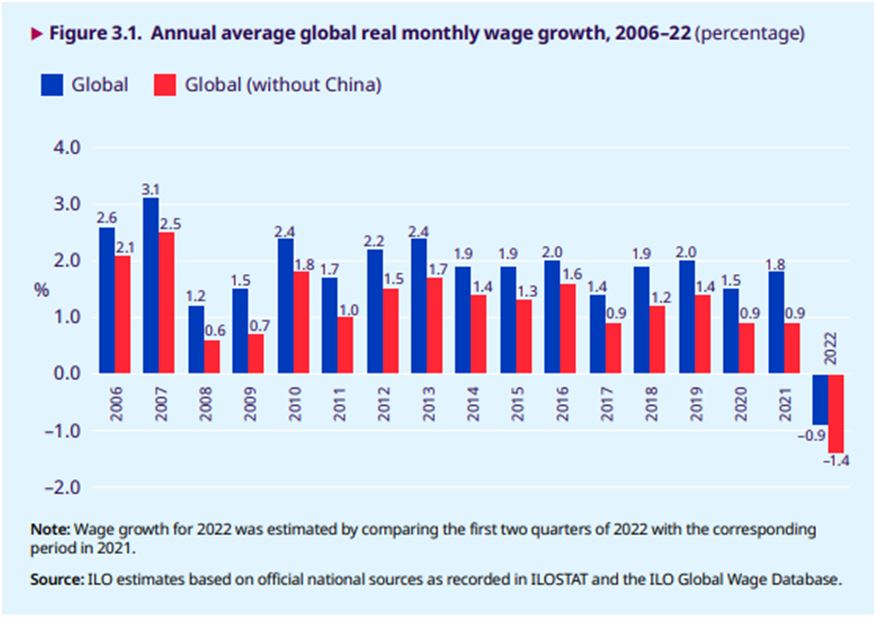

Chart 4. below is reproduced from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Global Wage Report 2022-23.

It shows the medium-term growth in real wages globally. 2022 was unprecedented in falling global real wages. This did not occur even in the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08. (Note too that global real wage growth in real terms is on average 0.6% lower when China is excluded. So much for the idea that China’s high levels of Investment are detrimental to popular prosperity).

Chart 4. Global Wage Report 2022-23 (ILO)

G7 policy caused this crisis

This factor is crucial in understanding the dynamic of the current crisis. Through the mechanism of inflation, in which real wages and other fixed incomes are lowered while profits are allowed to rise sharply, there is a sharp redistribution of incomes from workers and the poor towards big business and the rich.

The subsequent policy of raising interest rates by the central banks is billed as curbing an inflation that was created by official policy. But the further effect of those interest rate rises is to transfer incomes and wealth from small businesses, mortgage-holders and consumers to banks, big businesses and the owners of capital.

Naturally, G7 governments themselves are reluctant to accept the blame for the crisis. This leads to the string of explanations that have been offered that do not at all correspond to the facts.

However, in some of the more secluded areas of public debate where policy is discussed by those who advise policy makers in the leading economies and away from mass access, the veil has occasionally been lifted to reveal the true picture.

Below are small extracts from two research papers, which speak for themselves:

“Our findings suggest that fiscal stimulus boosted the consumption of goods without any noticeable impact on production, increasing excess demand pressures in good markets. As a result, fiscal support contributed to price tensions. Indeed, focusing on inflation through February 2022 which does not capture many disruptions associated with the war in Ukraine, we show that countries with large fiscal stimulus, or with high exposure to foreign stimulus through international trade, experienced stronger inflation outbursts.” –

Fiscal policy and excess inflation during Covid-19: a cross-country view, FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

And

“To mitigate the health and economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide engaged in massive fiscal support programs. We show that generous fiscal support is associated with an increase in the demand for consumption goods during the pandemic, but industrial production did not adjust quickly enough to meet the sharp increase in demand. This imbalance between supply and demand across countries contributed to high inflation. Our findings suggest a sizable role for fiscal policy in affecting price stability, above and beyond what a monetary authority can do.” –

Demand-Supply Imbalance in the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Fiscal Policy, Economic Research, Federal Bank of St Louis

Here the central bank economists and analysts could not be clearer: It was the role of G7 governments in stimulating the economy without any corresponding increase in production which caused inflation. Or, it can be put in another, starker way. The policy in the G7 was to stimulate Consumption, not Investment and the result was inflation.

However, it has been left to one of the world’s most senior central bankers to admit the role of the central banks’ monetary policy, not just government fiscal policy, in causing inflation:

“….monetary and fiscal policy stimulus deployed during the pandemic gave inflation an even larger, and certainly more enduring, unexpected push. As a reminder, policy interest rates were lowered to zero, and often below. Central bank balance sheets ballooned. Fiscal stimulus since the start of the pandemic has exceeded 10% of GDP in many advanced economies – a push previously seen only in wartime.” –

Monetary and fiscal policy as anchors of trust and stability, speech by Agustín Carstens, General Manager, Bank for International Settlements, at Columbia University, New York, 17 April 2023.

In fact, it has for some time been shown that it was G7 policy, both excessive government Consumption and monetary stimulus without Investment, which was the real cause of the crisis. Under the self-explanatory title, Global economic destabilisation was made in the US not in Ukraine, John Ross demonstrated that it was the reckless monetary and fiscal policies of the US which was the main cause of the crisis.

To this we can now add the following subsidiary but important points:

- This completely reckless policy was shared across the G7 in varying degrees

- All other explanations for the crisis have been shown to be false

- That the crisis was caused by G7 policy is now admitted, discreetly, by the central bankers themselves.

What next?

The G7 central bankers have decided to attempt to curb inflation by increasing borrowing costs rather than reining in excessive monetary stimulus or publicly suggesting that governments do the same with fiscal stimulus (which has overwhelmingly gone to big business). Never once have they suggested addressing the ‘demand-supply’ imbalances they have identified by increasing supply, that is, by significantly increasing Investment.

In the process of pushing interest rates higher, it is widely understood that interest rates charged to borrowers have risen far greater than the savings rates. The result is a huge increase in the profit margins of the banks. Just as with the profiteering of energy firms and both food producers and retailers who have taken advantage of the initial price surge by fattening profit margins, G7 governments could step in and impose price controls and windfall taxes, nationalising those who will not comply. But they have chosen not to.

This itself reveals that the current crisis is an all-round class offensive, which in a period of economic stagnation blatantly enriches further big business and the rich at the expense of impoverishing workers and the poor.

As noted earlier, this same offensive now includes increasing protectionism. Biden explicitly sold the Inflation-Reduction Act as a measure to protect household incomes and American jobs. It will do precisely the opposite.

Trump’s earlier protectionism raised prices and did nothing to protect jobs. As tariffs are paid either by importing businesses or consumers, domestic prices rise. At the same time, jobs tend to be exported to lower-tariff markets. Trump boasted that his protectionism would push GDP growth to 4% or above. In reality, average annual growth in his presidency was under 2.3% and continued the long downtrend in US growth rates.

This was predictable and predicted. That type of protectionism (of existing industries) has never worked, and the last time it became universal policy in the industrialised countries in the 1930s it led directly to slump followed by world war.

Bidenomics embraces Trump’s protectionism on a larger scale. European and British leaders pretend to welcome the measures while pleading for special treatment and exemptions. The upshot of this protectionism will be slower growth, fewer good jobs and higher prices than there would have been otherwise.

Global South debt

Yet, despite this level of economic difficulties, it is many countries in the Global South which will bear the brunt of the G7-induced crisis. In its recently released Global Economic Prospects the World Bank suggests that the economic growth of the Global South excluding China will fall from 4.1% in 2022 to 2.9% in 2023. The expectation is that the number of countries experiencing debt distress (and rising risk of default) will rise from the present number of 14.

The World Bank is clear that rising interest rates in the US are the cause of the nascent Global South debt crisis, even titling one chapter, ‘Financial spillovers of rising US interest rates’. This is a valid assessment of the process, reflecting the fact that the overwhelming bulk of Global South international borrowing is denominated in US Dollars.

When US domestic interest rates rise, Global South borrowers are obliged to increase the premium they must pay over US debt. But this comes at a time when, as previously noted, growth is also slowing markedly. This economic slowdown also tends to depress US Dollar-denominated export earnings in the Global South economies. This in turn reduces their capacity to meet interest payments on existing debt or renew existing borrowing.

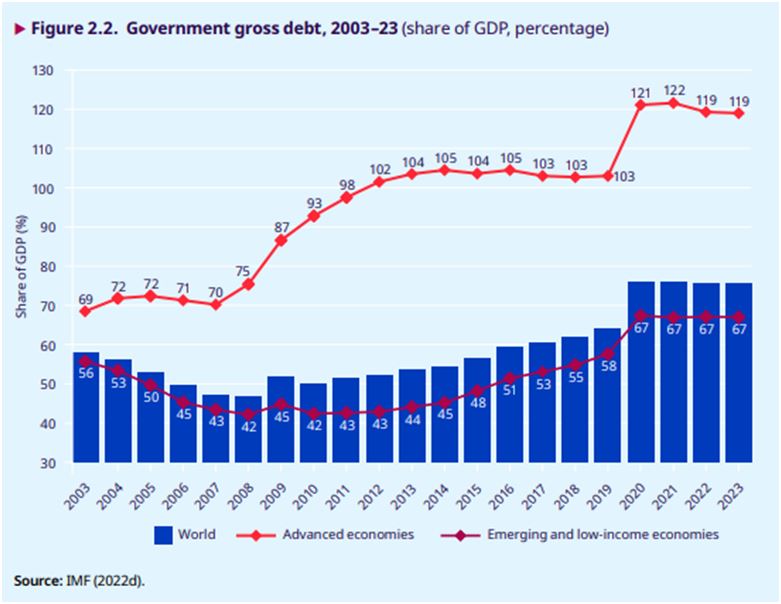

It is not the case that in general the Global South economies are relatively highly indebted. Taken in aggregate public debt in the Global South has been relatively stable and much lower as a proportion of GDP than in the advanced industrialised countries. This disparity is shown in Chart 5 below.

Chart 5. Public debt as a proportion of GDP in the advanced industrialised countries and in the Global South

Source: ILO

Naturally, there are specific instances of much higher public debt of some countries in both regions. But it cannot be said that it is generally high Global South indebtedness which is the cause of the debt crisis. It is the combination of factors of dependence on the slowing G7 economies, the impact of higher US interest rates and above all the existing levels of very high interest rates on public debt, whose gap over US domestic interest rates tends to rise even as US rates are rising.

In short, the crisis is caused by US dominance of global financial markets and the impact that has on the borrowing costs of the Global South. This aspect of the crisis is still developing and may have much further to run, depending on the trajectory of US domestic interest rates.

We are all going to pay the price for the failed economic ideology and reckless policies of the G7 governments and central bankers. But some will pay more heavily than others.

Recent Comments