The crisis in the NI economy never really ended

By Tom O’Leary

The latest release of key data for Northern Ireland (NI) has had business organisations wringing their hands about the weakness of the economy. The CBI said the economy “looks to be on the brink of recessionary territory” after the economy contracted in the 1st quarter of 2018. In fact, the economy has contracted in three of the last four quarters.

But this is not a short-term problem. Over the longer run, it is clear that NI economy has never recovered from the Great Recession. It remains in a crisis.

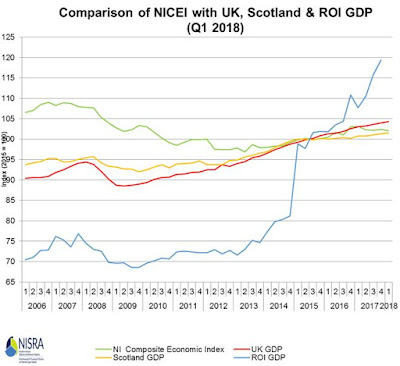

Chart 1 below shows a comparison of overall growth rates for NI, Scotland, for the UK and for the Irish Republic (RoI). It is reproduced from the Northern Ireland Statistical Research Agency (NISRA).

The Northern Ireland Composite Economic Indicator (NICEI) is very far from being as authoritative as a measure of GDP. But it is the most advanced measure so far developed, and movements in the Index are likely to be good indicators of the trends in NI output overall.

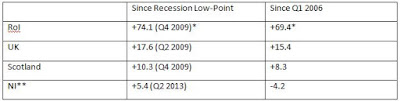

The chart shows that the overall level of output in NI has been exceptionally weak even on a comparative basis. This is highlighted in the table below, which shows the level of growth since the low-point of the recessions in the respective countries or regions, as well as the level of growth since the 1st quarter of 2006, the first available data.

**NICEI, others GDP

Source: NISRA

Even if the data for RoI is disregarded entirely, based on the widely remarked upward distortions to GDP, the comparative performance of the NI economy has been miserable. This is despite the fact that UK-wide and Scottish growth rates have themselves been extremely weak over the period.

[The economy of the RoI has hugely inflated GDP levels, based on the government policy of attracting spurious investment from overseas, which is in reality a tax avoidance scheme. As a result, much economic data is meaningless. However, on one real measure RoI’s total real wages have risen by a very slow 7.4% over the last 10 years. Yet even this miserable level compares favourably to -3.75% for the UK over the same period].

As the Table shows the NI recession lasted 3½ years to 4 years longer than elsewhere. The NI recession only ended in the 2nd half of 2013. The recovery since that low-point has also been minimal. And the level of output in the NI economy still remains more than 4% below its pre-recession peak. The other economies have all recovered, at least to some extent.

Looking wider, most of the EU countries hit hardest by the Great Recession have made some sort of recovery, including Spain and Portugal. Italy is one of the worst-performing major economies in the world. Since the 1st quarter of 2006 the Italian economy has contracted by 2.4%. But the NI economy has been even worse. Only the ravages inflicted on Greece in the interests of its creditors put it in a separate category, having contracted by 21% since the beginning of 2006.

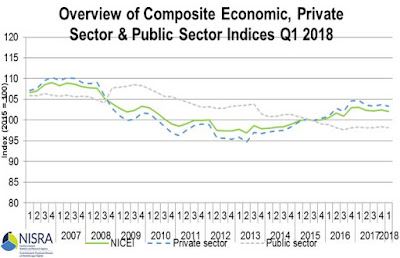

Disastrous public-private partnership

The disastrous performance of the NI economy has two sources, both the private sector and the public sector. As Chart 2 below shows, both the private and the public sectors have contracted since 2007. When the Tories came to office in 2010 they abruptly reversed the growth in the short-term rise in the public sector, which had been promoted in 2009 in response to recession.

Meanwhile, the NI private sector went into recession at the beginning of 2007, probably reflecting its links to and dependence on the private sector in RoI, where the recession began before the recession in the UK.

Recent Comments