The cash hoard of Western companiesBy Michael Burke

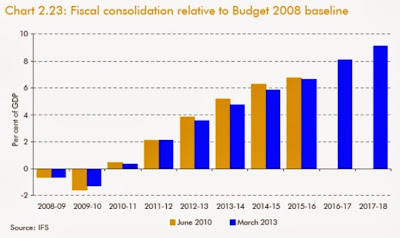

Supporters of ‘austerity’ would have a very strong argument if there really were no money left. In that case, opponents of current policy would be left arguing only for a fairer implementation of those policies, or that perhaps they could be implemented more slowly.

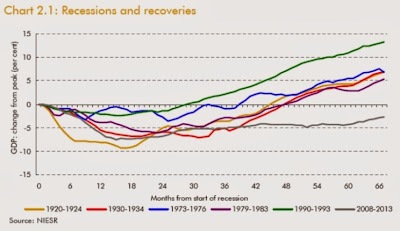

This is not the case. Firms in the leading capitalist economies have been investing a declining proportion of their profits. This is the cause of the prolonged period of slow growth prior to the crisis and a number of its features such as stagnant real wages, so-called ‘financialisation’ and the growth in household debt.

This negative trend of declining proportion of profits directed towards investment reached crisis proportions in 2008 and is the cause of the slump. As a consequence of the sharp fall in this investment ratio there has been a sharp rise in the both the capital distributed to shareholders and in the growth of a cash hoard held by Non-Financial Corporations (NFCs). This cash hoard is a barrier to recovery, releasing it could be the mechanism for resolving the crisis.

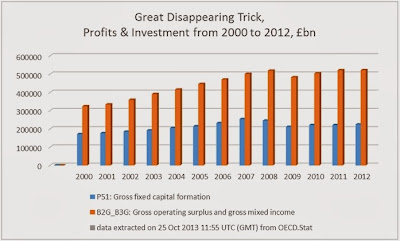

The chart below shows the level of surplus generated by US firms (Gross Operating Surplus) and the level of investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) for the whole economy. Since the former are only presented in nominal terms, both variables are presented here in the comparable way.

Fig.1

The nominal increase in profits has not been matched by an increase in nominal investment. In 1971 the investment ratio (GFCF/GoS) was 62%. It peaked in 1979 at 69% but even by 2000 it was still over 61%.

It declined steadily to 56% in 2008. But in 2012 it had declined to just 46%.

In a truly dynamic market economy there is nothing to prevent the investment ratio from exceeding 100% as firms utilise resources greater than their own (borrowing) in order to invest and achieve greater returns.

Therefore even an investment ratio of 69% is sign of a less than vigorous market economy.

However the subsequent decline in the investment ratio to 46% is a sign of enfeeblement. If US firms investment ratio were simply to return to its level of 1979 the nominal increase in investment compared to 2012 levels would be over US$1.5 trillion, approaching 10% of GDP. This would be enough to resolve the current crisis, although it would not prevent the re-emergence of later crises.

Distribution of profits

The uninvested portion of firms’ surplus essentially has only two destinations, either as a a return to the holders of capital (both bondholders and shareholders), or is hoarded in the form of financial assets. In the case of the US and other leading capitalist economies both phenomena have been observed. The nominal returns to capital have risen (even while the investment ratio has fallen) and financial assets including cash balances have also risen. One estimate of the former shows the dividend payout to shareholders doubling in the 8 years to 2012, an increase of US$320bn per annum.

The growth of cash balances is shown in the following data from the Federal Reserve. They are the changes in key balance sheet aggregates for US non-financial corporations from 2008 to Q2 2013.

Change in Balance Sheet Components, US NFCs, 2008 to Q2 2013, US$bn.

|

2008 |

Q2 2012 |

Change |

| Total assets |

29,881 |

33,662 |

3,781 |

| Total net assets (deducting liabilities) |

16,656 |

19,470 |

2,814 |

| Non-financial assets |

16,945 |

17,686 |

741 |

| Financial assets |

12,937 |

15,975 |

3,038 |

| -checkable deposits |

14 |

386 |

372 |

| -time deposits |

382 |

597 |

215 |

|

|

|

|

-non-financial item:

Business equipment |

3,896 |

4,191 |

295 |

Source: Federal Reserve

Total assets of US NFCs have risen by nearly US$4trillion over the period which is equivalent to approximately 25% of US GDP. The increase in net assets of US$2.8bn (after accounting for the rise in liabilities over the same period) is more than accounted for by a rise in financial assets of over US$3 trillion.

By comparison the rise in the current cost value of business equipment has been less than one-tenth that (and is accounted for by inflation).

Within the rise of financial assets, cash or near-cash instruments have contributed a rise of nearly $600bn (the biggest single contributor in the accounts is ‘miscellaneous financial assets’).

Generalised phenomena

The same is true in other capitalist economies. In 1995 the investment ratio in the Euro Area was 51.7% and by 2008 it was 53.2%. It fell to 47.1% in 2012. In Britain the investment ratio peaked at 76% in 1975 but by 2008 had fallen to 53%. In 2012 it was just 42.9% (OECD data).

The cash hoards are no less striking. The total deposits of NFCs in the Euro Area rose to €1,763bn in July 2013 of which €1,148bn is overnight deposits. This is a rise of €336bn since January 2008, nearly all of which is in overnight deposits, €306bn. In Britain the rise in NFCs bank deposits has been from £76bn at end 2008 to £419bn by July 2013.

In reality, this extraordinary accumulation of cash by NFCs began well before the immediate depression in 2008, along with the slump in investment. Both of these merit further elaboration elsewhere.

Conclusion

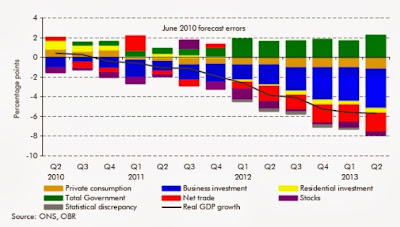

The profitability (profit rate) of US firms and firms in other Western economies has fallen, and even the absolute mass of profits fell for a period in the recession. While the former has not recovered, the latter has. But this has not led to a corresponding rise in investment and the investment ratio has fallen sharply.

The destination of of these uninvested profits is twofold. Owners of capital are in receipt of record payouts. And the financial assets of NFCs have risen dramatically, often primarily cash as firms are unwilling to risk any type of investment.

This hoarded store of capital is both the main impediment to recovery and the potential source of resolving the current phase of the crisis.

Recent Comments