.708ZWhat do Britain’s private sector firms contribute?By Michael Burke

The main factors that account for economic growth are increases in the workforce or in the amount of productive capital in the economy. A far smaller contribution is made by improvement in productivity as a result of innovation, which is known as Total Factor Productivity.

Since mid-2009 the British economy has grown. But this is wholly accounted for by growth in the workforce, which made up of both an increase in the number of people in work and in the number of hours they work. As a result the average person in work cannot experience any improvement in living standards as economic growth is simply made up of more people working longer hours. Worse, those on very high pay, senior executives and shareholders, have claimed any benefits of that moderate growth in the British economy. Average real pay continues to decline.

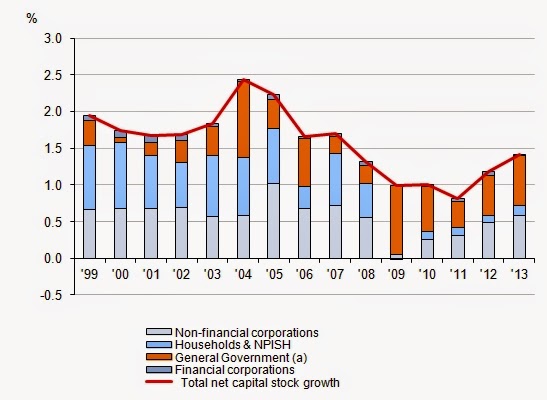

The missing element in Osborne’s so-called recovery has been growth in productive investment. The ONS chart below shows the level of Net Fixed Capital Formation in the British economy from 1999 to 2013 as a proportion of GDP. Usually Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) is the main indicator of investment that is discussed. But Net Fixed Capital Formation deducts the capital consumed in the production process itself. While GFCF includes replacement of machine tools, or software and repairs to a factory, NFCF is a measure of only the net addition to new machine tools, software or factories after any replacements have been deducted.

NFCF therefore measures the addition to the accumulated stock of capital. (Unfortunately it also mixes together productive capital, such as machinery, with unproductive capital such as housing, but this failing cannot be addressed in this piece). The chart also shows the contribution to NFCF from each sector, non-financial firms, financial firms, government and households.

The data is worth examining in detail. The net contribution of financial firms can be disregarded as it is negligible in all cases. But it is also clear that the contribution of non-financial corporations (NFCs), i.e. private companies, has been far from overwhelming.

In most years before the crisis the net contribution from non-financial firms was matched or surpassed by the contribution from households (and the non-profit sector NIPISH). The strongest year for the net growth in the capital stock was 2004, when the greater role was played by government and non-financial firms contributed just one quarter of the total growth. But this increase in government spending encouraged the private sector and the following year saw an increase in the contribution to NFCF by private firms. But from that point onwards until 2009 government NFCF was once again reduced and in turn, with one year time lag, companies duly cut their own level of investment. With a time lag, companies also followed when government increased its investment again after 2008. Yet non-financial firms never contributed as much as half of the net growth in the capital stock in any year over the period.

Outlook

The coalition government has been claiming that it has overseen a revival of the British economy, including business investment. But the total proportion of NFCF is barely changed from the crisis year of 2008, along with the contribution from non-financial firms. In reality, it was the modest increase in government net investment in 2009 which rescued the economy and has been responsible for well over half the growth in net investment since. Non-financial firms have contributed less than a third of the NFCF over the same period. Yet the Coalition cut the level of investment it inherited from Labour and has only increased it modestly to avoid the political consequences of a renewed recession.

Over the longer-term Britain has a very low level of net capital formation, less than 2.5% of GDP at its recent high-point, which condemns the economy to slow growth. Even among the Western economies that have experienced a decline in growth rates over the medium term, Britain has had one of the lower levels of NFCF. It is notable too that the US has among the weaker levels of net investment growth since 2006, which belies notions about a US industrial renaissance.

Unfortunately, the Thatcherite and Reaganite notion of the ‘state getting out of the way of the private sector’ still dominates thinking in most Western economies. This turns reality on its head. Private firms are an important but minor player in the growth of the net stock of capital. They are led by the activity of the government. This was decisive during the crisis and there is no prospect of a return even to previous levels of British growth if it is mainly dependent on the contribution of private firms. The austerity consensus remains that government must cut back while we await the decision of private firms to increase their investment. This will condemn the economy to prolonged stagnation.

Recent Comments