Illusion of the narrowing trade gap

By Tom O’Leary

A recent Times editorial castigated the new International Trade Secretary Liam Fox for his foolish remarks regarding the laziness of British business executives. If The Times is going to criticise every stupid pronouncement by the three new ministers for Brexit, there will be little room for any other comment.

But the editorial also betrayed a lack of knowledge about elementary economics. And, as the assertions made about what prevents Britain being a greater or even an important participant in international trade are widely held, they are worth rebutting. The editorial states that,

“We should…complain about export growth. It is true that too few British companies succeed abroad. This is partly because they struggle to compete with rivals in India and China that spend less on wages. It is partly because companies selling services do not always find willing buyers in those markets. It is furthermore a reflection of lack of ambition.”

So, not laziness, but ‘lack of ambition’ and lower wages in India and China are the sources of British export weakness. This is plain nonsense.

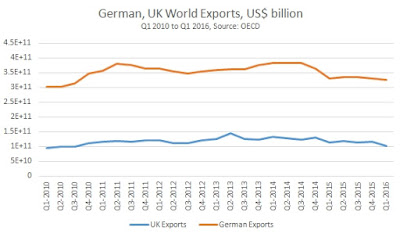

The chart in Fig.1 below shows the level of total exports to the world from UK and from Europe’s export powerhouse Germany. In the most recent quarter UK exports to the world were valued at US$100bn while German exports were valued at US$326bn. Germany has a population about one quarter again as big as the UK and its economy is approximately 40% larger. Yet German exports are more than 3 times greater than those from the UK. Germany has struggled under the weight of slow global growth. Even so, Germany’s export performances is vastly greater than that of the UK economy, even though Indian and Chinese wages are just as low for German manufacturers as they are for British ones.

A key reason why German exports are more than 3 times greater than UK exports is that the German economy is much more integrated into global supply chains. This also means that Germany’s imports are also far greater than the UK’s. But Germany also provides a much higher level of value added to the imported raw materials and inputs of intermediate and capital goods. By contrast the UK is more usually the final destination of its imports, the final consumer of goods not the final producer of finished goods.

Currency Devaluations

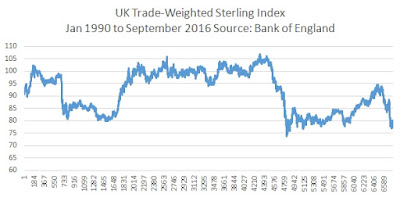

The widely expressed hope is that the devaluation of the pound will lead to a revival of exports. Sterling’s trade-weight currency index (a basket of currencies weighted according to UK trade) has fallen by around 10% since just before the Brexit referendum and has fallen by 18% since mid-November 2015.

Currency devaluations can boost exports. They also raise the price of imports and so lowers the living standards of the population. Viewed domestically, devaluations represent a transfer of incomes from consumers to producers.

Exporters benefit because their key cost is now lower in international terms, wages. Other inputs such as energy and raw material, as well inputs of semi-finished or intermediate goods produced abroad will all eventually rise to adjust to the new exchange rate.

The long run history of the British economy is punctuated by repeated and very sharp devaluations. Yet Britain’s share of world trade has continued to decline and is now a fraction of former competitors such as Germany.

The devaluations are a product of economic weakness driven by underinvestment. UK exporters have not responded to devaluations with increased investment, but have simply temporarily increased profit margins. As competitors continue to invest at a greater rate this cost advantage is eroded and the cycle of declining competitiveness and devaluations sets in once again.

Will this time be different? There is no evidence that it will be. The British Chambers of Commerce is just the latest organisation to forecast reduced business investment in the period ahead. This follows similarly gloomy forecasts from the Bank of England, Markit Purchasing Managers surveys, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in the England and Wales, as well as others.

The structural impediment is that the UK economy is not sufficiently integrated into global supply chains. With a few exceptions, such as aerospace, cars and a small number of others, UK industry is not part of the leading European or global industrial sectors. There is no other route to increasing that participation other than increased trade links with the rest of the world based on significantly increased industrial investment (not increased bluster from the Tory Ministerial Brexiteers).

The latest international trade data showed a narrowing of the trade gap, Fig.3 below. The much-heralded rise in exports in the data, held to vindicate Brexit, is simply an exchange rate illusion. Most trade internationally is conducted in US Dollars. The falling level of the pound against the US Dollar raises the value of exports in Pound terms, which is how the trade data is naturally reported.

But the ONS also reports trade data on a volume basis. In July, following the devaluation the total volume of UK exports fell 0.2% from June and were just 1.1% higher than a year ago. The narrowing of the trade gap arose from a 3.8% fall in import volumes from June, and they were just 1.2% higher than a year ago.

There is no evidence to date that exports will rise on a sustained basis following the devaluation. It is possible that the trade balance will narrow for a period because incomes have fallen on an international purchasing power basis, poorer firms or households cannot afford the same level of imports. The trade gap may narrow, but only because the UK is poorer. Using the weakness of the pound to improve living standards would require an investment-based reindustrialisation strategy.

Recent Comments