By Tom O’Leary

Portugal is finally on the brink of ending the slump that began with the Great Recession at the start of 2008. But the economy remains far from a full recovery and important challenges lie ahead for the Left-supported government.

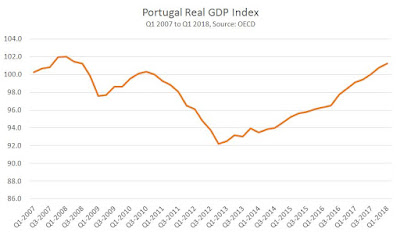

In the 1stquarter of 2018 the level of Portuguese GDP rose once more and is now just 0.75% below its level of the 1st quarter of 2008, which was immediately followed by recession. At some point this year the economy will finally surpass its pre-recession peak level. The low-point of the recession was reached in 4th quarter of 2012.

From the pre-recession peak in early 2008 to the low-point of activity and the end of 2012 the economy contracted by 9.6%, one of the sharpest falls in the whole of Europe (although less than half the depth of the Greek catastrophe). Since the end of 2012 the economy has been expanding.

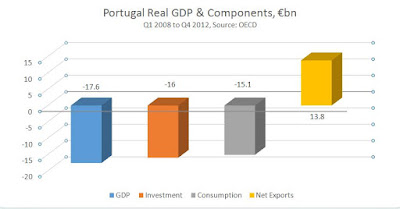

The content of the crisis was twofold. Consumption fell by €15.1 billion, taking both government and private Consumption together. Investment fell by the even greater amount of €16 billion, even though Investment was a far smaller proportion of GDP. In percentage terms Consumption (private and government combined) fell by 9.7% in the slump, in line with economy as a whole. Investment fell by a far greater amount in percentage terms, down 36.25%.

As with other countries, the main driving force of the Portuguese crisis was therefore the slump in Investment. Chart 1 below shows the change in real GDP and its components during the slump. Net exports rose over the period, partly off-setting the sharp falls on other GDP components. But this was overwhelmingly due to a slump in import demand, not a surge in exports.

The impositions of the Troika have had a devastating effect on the Portuguese economy. The ‘bailout’ was not for Portuguese workers and the poor. It was a bailout of the creditors of the Portuguese government, who included both Portuguese and international banks, as well as investment and hedge funds, and other vultures. Vicious austerity was the price the Portuguese population was made to pay. They were also burdened with the debts of the creditors.

It is important to register the actual timeline and causality of the crisis. The Portuguese government did not apply for Troika a bailout until April 2011. The government had already imposed austerity measures of its own under the pressure of European Central Bank, the ratings’ agencies and others. Before the bailout of creditors the economy had already contracted by 3.1% and Investment had fallen by 20%. This was a crisis initiated by Portuguese and international big business, and a government acting in their interests. The Troika formalised and deepened that process.

Turning to the recovery, as Chart 2 below shows, that expansion has clearly accelerated since the beginning of 2016. This coincides with the new government in office, the Socialist minority government supported by the Left Bloc, the Communists and the Greens.

The acceleration under the Socialists is clear from the evidence. In the first 3 years since the economy began to expand once more, from 2013 to 2015 GDP rose by just 4.2%. But the signifcant acceleration in growth from 2016 onwards means the economy has expanded by 5.3% in little over two years.

The sharp change of policy under the new government is associated with the acceleration of growth. The Socialists, and the other parties supporting it in forming a government, stopped imposing new austerity measures. This alone has been enough to prompt an economic recovery.

To be clear, it is not increased government spending which has caused a recovery. The government has not increased its own Consumption at all. According to OECD data the annual level of government Consumption was €34.256 billion in the 4thquarter 2015, the last of the outgoing government. It was barely changed at €34.494 billion in the 1st quarter of 2018. The idea that increased government ‘stimulus spending’ has prompted Portugal’s recovery is not factually correct.

Instead, the government stopped imposing new austerity measures. This allowed a rise in private Consumption, and an increase in Investment, which is shown in Chart 3 below. Investment remains very far from recovery. But it has been on an accelerating trend. In the 3 years after 2012 when the economy began to expand once more, Investment rose by 9.0%. In little more than two years of the Socialist minority government investment has increased by 14.6%.

The decisive factor in continuing to ensure sustained growth will be to extend and improve this upturn in Investment.

As already shown, the fall in Investment was the decisive element in provoking the recession. The major fall in living standards came later, imposed by the Troika. In order to maintain recovery, raise living standards and undo the impact of the crisis, the further expansion of Investment is required.

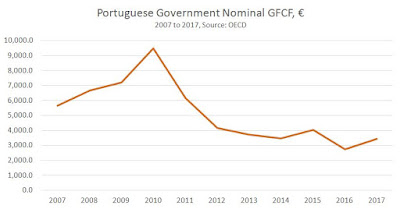

Before the crisis, Investment comprised over 22% of GDP. It is now just 16% of GDP. If that Investment share of GDP is not restored or improved, it will be difficult to sustain the same pre-crisis levels of growth in living standards. General government Investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) has only just begun to turn up. Chart 4 below shows the Nominal level of general government Investment.

Given the time leads for Investment (in transport, infrastructure, affordable housing, ports and so on) the new government can only be responsible for the level of public Investment in 2017. This showed a modest upturn.

The private sector cannot be relied on to maintain increased Investment. The Government must significantly increase its own Investment to maintain recovery over the medium-term, and to underpin rising living standards.

The IMF has called on the government to increase lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This is entirely the wrong prescription. SMEs will never deliver the large-scale Investment the economy requires, or direct towards the areas required, in housing, infrastructure, transport, new technologies and so on. Instead, the government should invest on its own account to achieve the increase in the productive capacity of the economy that is required.

How precisely that is achieved would require detailed knowledge greater than the current author’s. But the following options would come under consideration:

*Borrowing for investment – a public sector budget surplus is now expected and Eurozone government interest rates are extremely low

*Pressing for increased investment from the European Investment Bank and other supranational bodies

* Using remaining state-owned companies to increase their own investment

*Encouraging productive (not speculative) Investment in the real economy through Foreign Direct Investment.

Other avenues may also be possible. The decisive issue is to maximise the level of Investment to boost sustainable growth and living standards. This is the major challenge ahead.

Recent Comments