By Michael Burke

In an era of blatant lies, the claim that this Tory government is trying to push wages higher and create a high wage economy stands with some of the most shameless fabrications of all.

The entire thrust of government policy is to drive wages lower in order to boost profitability. This is logical, from the perspective of those addressing the crises of the British economy by prioritising a rise in profits.

However, another policy with the same aim in mind, Brexit, has back-fired as far as this government is concerned, and for the interests of the ruling class in general. The effects of Brexit are so negative and far-reaching that it has created a labour shortage, which was never part of the plan. Just as critics of Brexit warned, non-tariff barriers would have reduced both the supply of goods and services as well as raising their price. These new non-tariff barriers, which have not yet been fully put in place, are now described as ‘supply-chain issues’, but are actually Brexit effects, as will be shown below.

However, it is not at all true that Brexit, or government policy is leading to higher wages. These are negative effects for the population as a whole as energy and food bills are already soaring at a time when workers generally are being hammered, including very significant job losses.

Crucially, the shortages of labour and skills are driven by a wholly unanticipated development; primarily the exodus of British-born workers after Brexit.

Driving down pay, and keeping it there

There is a strange reluctance on the part of many, even among government critics to accept the reality that the labour market in Britain is in very poor state and that workers generally are struggling with shorter hours, lower pay and worse conditions.

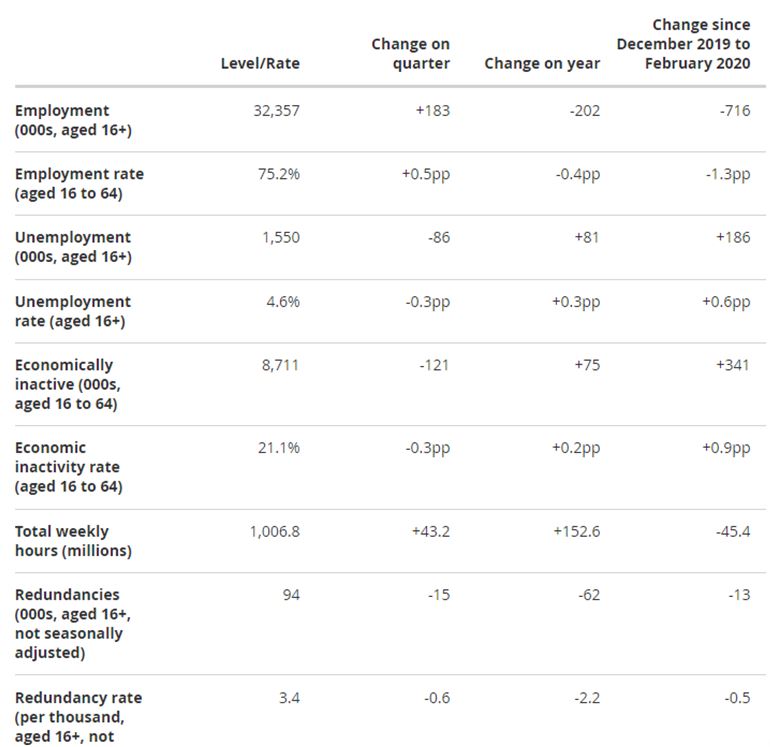

So, to avoid any charge of cherry-picking data to suit an argument below, is a table produced in the most recent Office for National Statistics (ONS) labour market report for September.

Table 1. UK headline economic status levels and rates, total weekly hours, and redundancy levels and rates, seasonally adjusted (unless otherwise stated), May to July 2021

Source: ONS

The change in all key indicators since the pandemic began is show in the last column. So, 716,000 people are newly unemployed over the period, the unemployment rate has risen 1.3%, the unemployment total has risen by 186,000, and so on.

All of these represent a partial rebound from the lows seen since the pandemic began. But the pandemic is far from over, as international bodies such as the IMF now warn, having previously based unfeasibly strong growth forecasts on the assumption that the pandemic was coming to an end. There is too an immediate threat as the furlough scheme ended at the beginning of October, which was still supporting 1.6 million workers. No-one can know in advance how many further job losses will be caused as a result, but one survey suggests that 70% of these employers will cut at least some jobs.

The generalised effect of much higher unemployment is to create the ‘reserve army of labour’, just as Marx analysed, which has the effect of driving down wages for those in work. This is an aim of government policy, and is supplemented by other policies to weaken the bargaining power of labour, everything from fire and rehire to curbing the right to protest.

Not so fast on pay

One area of genuine confusion, fostered by the government and supportive commentators is on the trends in pay. Boris Johnson says that pensioners will not receive the promised ‘triple-lock’ uplift in pensions linked to sharply rising pay because it is a statistical aberration. He also says that the same rise in pay is evidence that his long-held(!) aim of increasing wages is bearing fruit. As usual, neither claim is true.

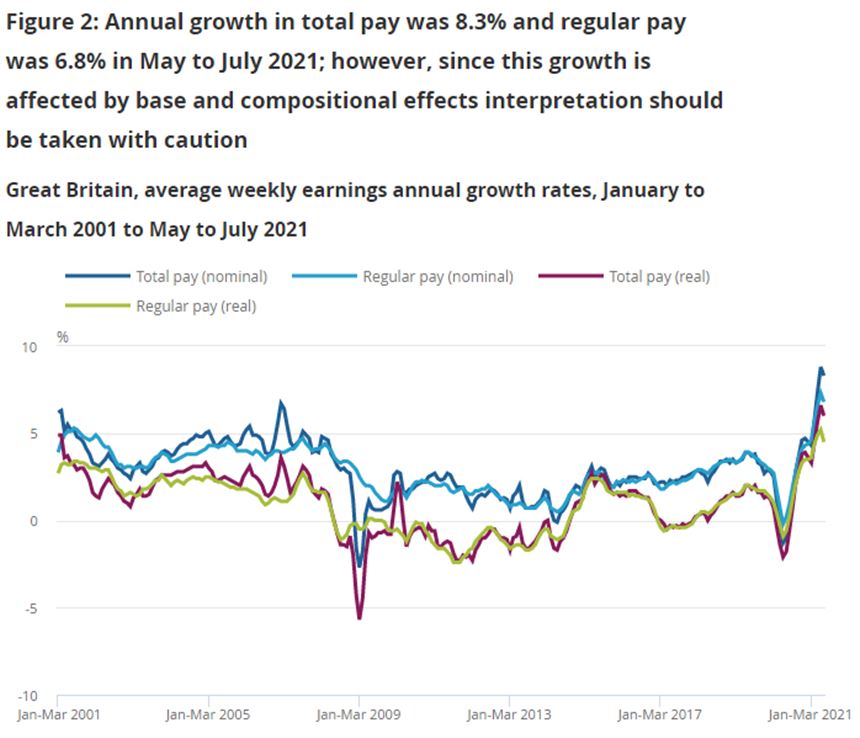

Chart 1 Annual Pay Growth

Source: ONS

Chart 1 from the ONS above shows various measures of wage growth, with and without bonuses and in nominal or real terms (adjusted for inflation). These range from 8.3% for nominal total pay (including bonuses) to 4.5% for regular real pay.

But ONS issues two notes of caution in using the data. The first is the comparison with a depressed economy a year ago, when total real pay fell by 1.8% across the economy. Compared to two years ago and before the pandemic, real total pay is up just 3.5% over the 2-year period. Secondly, the ONS statisticians warn about compositional effects. Over the past period, by far the biggest portion of job losses (of 716,000 in total) have been among part-time and low-paid workers. The average pay of the remainder, those still in work rises simply because the lower paid drop out of the calculations.

There is no boom in wages. Assertions of this kind, either from government supporters or Brexit supporters are completely false.

In addition, it should be absolutely clear that the government which imposed a pay freeze on the public sector has never had a plan for higher wages. The opposite is the case. The aim of the public sector pay freeze has nothing to do with controlling public finances. After the £37 billion debacle of test and trace, and over £400 billion spent on business subsidies during the pandemic to date, even ministers know they would struggle to amount that case.

The aim is to set a ‘going rate’ in the economy as a whole which is close to zero for all pay rises, including the private sector. In mainstream economic jargon this is a ‘demonstration effect’, to curb wages. This is necessary, from the perspective of the architects of the policy, because even after more than a decade of austerity it is uncertain whether there has been any decisive impact on the crisis of profitability in the British economy, as SEB has previously shown. The actual policy is to push wages lower in real terms, to restore profitability.

The reason the government has been stymied, at least temporarily, is because of Brexit and a wholly unforeseen effect on the supply of labour. In typical fashion, this Prime Minister has turned an unwelcome and unforeseen development of higher pay into a claimed long-held policy aim. It is not just a lie, it is nonsense.

Brexit effect

It is undoubtedly true that other countries are experiencing problems of supply. This follows a period of disinvestment by firms in the advanced industrial economies the pandemic and is a consequence of it.

To take a widely-experienced example, there is a general shortage of truckers and HGV drivers. During the lockdown phases of the pandemic there was natural wastage as the normal retirement rate took place, but this was increased as many others took early retirement or took other jobs for lack of work. In many instances, the drivers are self-employed and have had little or no financial support during the pandemic. But in addition to these elements, firms did not hire and train new drivers as work for them was limited.

All of these factors explain the general shortage. But, while truckers and HGV drivers move around in response to work across Europe, Brexit means Britain has cut itself off from the supply chain for transport services. In plain language, HGV driver do not want to come here, or work overseas from Britain. This economy has severed links to that supply chain via Brexit.

These Brexit problems (which are not solely about foreign workers coming to this country, but deter all drivers from crossing to and from Europe) are creating shortages and driving up wages in the sector. The same is reported in other sectors, such as seasonal agricultural workers, butchers, and others that may only now come to light.

These labour and skills shortages are also directly feeding into shortages of goods and higher prices, from fuels, to food, to pharmaceuticals. All these are predicted Brexit effects.

None of this is meant to suggest the EU is a progressive entity. It is not. But neither is the British state. Instead, Brexit has meant a severing of supply chains that extended to this economy, a cutting off from markets and a reduction in the productivity of both labour and capital as a result. Brexit is a significant negative economic shock.

Some suppliers have diverted goods away from British markets because of the costs associated with the new non-tariff barriers, and British and EU drivers will not wait at the Channel ports for their paperwork to be checked, unpaid while they are not making mileage.

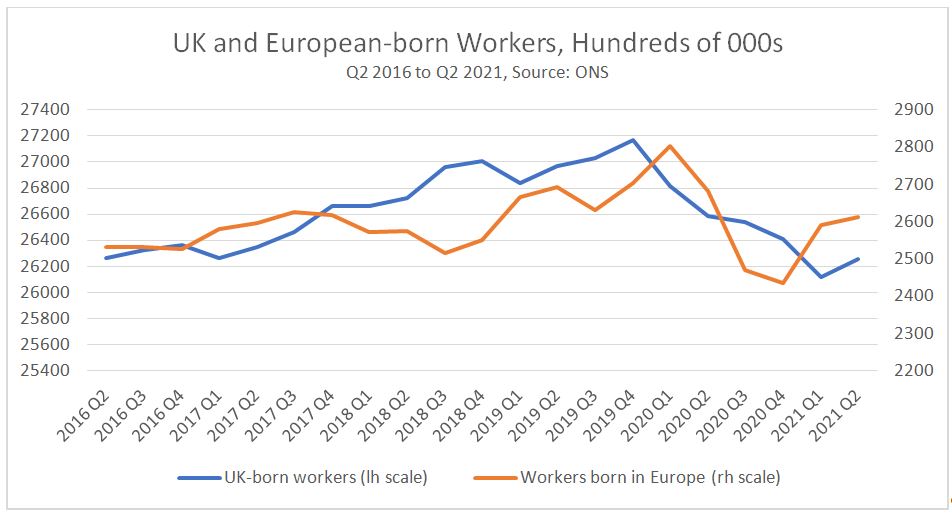

Perhaps the most startling and least understood aspect of the Brexit shock is the composition of the exodus of workers because of Brexit. This belies the claims of the government/Brexiteers that fewer foreign workers have led to higher wages. This surprising composition is shown in Chart 2 below.

Chart 2. UK and European-born Workers

Source: ONS

It is widely but incorrectly asserted that the labour and skill shortages are driven by the flight of EU workers in response to Brexit. There has been a significant decline in the number of EU workers in this country, although this has been offset to some extent by a net inflow of non-EU European workers.

As a result, Chart 2 above shows the number of total European-born workers in the British economy (orange line, right-hand scale). There are around 200,000 fewer European workers than at the beginning of 2020, when it was clear that the Tory election victory meant there would be a hard Brexit and harsh immigration/visa regime replacing Freedom of Movement (FoM).

But there has been a much steeper decline in the numbers of British-born workers over broadly the same period (blue line, left-hand scale). The total net decline in these workers has been well over 900,000. This far outstrips the net decline in the numbers of workers from Europe, and is the main Brexit effect on the supply of labour.

There may be a number of reasons for this outsized level of exiting the labour market in this country, that lie beyond the scope of this piece. In addition to discouraged workers, there has been a long-term outflow of British-born workers to other countries, which may have continued even without the benefits of FoM. In addition, reactionary immigration regulations mean that birth in Britain does not confer citizenship or residency rights, and spousal rights of residency were also abolished with the end of FoM. Others may have moved abroad because partners or other family members no longer had rights of residency or work. There may be other, unknown motivations.

However, it is clear that by far the biggest Brexit impact on the availability of skills and labour is from British-born workers leaving employment (916,000 lower the peak level) rather than European workers (192,000 lower).

Conclusion

The government’s plan is to cut wages in the British economy in order to push up profitability. This is clear from pay freezes, fire and rehire, and furlough on 80% of pay and which now ends even though the pandemic effects are stronger now than this time last year.

However, the government has run into a significant hurdle of its own making, through the disastrous Brexit policy. Barriers and bottle-necks created by Brexit, and higher global energy prices caused by a failure to invest for the duration of the pandemic, have been exacerbated here because Britain cut itself off from its own supply-chains.

There has been a significant outflow of workers, out of the workforce and out of the country, which has created shortages of labour and skills. At least temporarily this is causing upward wage pressures in certain sectors. It is overwhelmingly driven by the outflow of British-born workers, not workers from the EU.

For the population as a whole, the effect of Brexit is to create shortages, including shortages of essential goods, as well higher prices. Brexit has made the overwhelming majority worse off. The current trends in energy prices, where Britain has left itself completely exposed at the end of the European supply chains (and adopted a laissez faire approach to energy purchasing), points to higher prices in general.

Higher prices are a consequence of government policy and lower wages an aim. The government has taken a series of measures to ensure the latter. However, a Brexit project that is designed to benefit US capital above all, and to encourage British capital to emulate that economic model has driven away workers as much as discouraging new ones. That Brexit effect stymies the overall economic plan, as labour shortages have led to higher wages in some areas.

So, a new fiction is created. The government is not aiming for higher wages, as it claims. It is now aiming for higher prices, which will lower all wages in real terms.

Recent Comments