By Michael Burke

Rachel Reeves’ statement on public finances on July 29 was the opening shots of what seems set to be a long war of renewed austerity. Just as Tory Chancellor George Osborne did in 2010, Reeves has blamed the previous government for forcing the new administration into cuts. His accusation of ‘failure to fix the roof while the sun was shining’ has become her ‘failure to fix the foundations’. But in both cases they are part of a spurious PR campaign intended to provide the mantra for a long campaign of cuts.

Yet one crucial difference remains. Successful industrial action against real cuts to pay gained huge popular support. The actual pay curbs were successfully beaten back over time and are now being reversed. The strength of the industrial action and the popular support for it was undoubtedly a factor in the last government’s unpopularity and eventual defeat. Now, a Labour government is imposing new round of austerity – but dares not include public sector pay.

Why cuts?

There is no doubt that the charge against Sunak and Hunt in particular that they ‘cooked the books’ is fully justified. As the Treasury’s own analysis (pdf) shows, the subterfuge dates back from 2021 onwards, and includes a whole series of commitments on spending which were not included in subsequent Budgets. Half of the £22bn shortfall in public finances arises from sticking to exceptionally low public sector pay forecasts, even when these had already been substantially exceeded.

However, the logic that these must be dealt with by cuts to public spending is entirely spurious. The cuts themselves are wide-ranging:

- £3.1bn in departmental budgets

- £2.4bn in winter fuel payments, adversely affecting millions of pensioners

- Planned cuts in the building of 40 hospitals

- Similar cuts for roads

To this list could be added the refusal to end the 2-child benefit limit and reneging on the promise to cap the costs of social care.

In addition, the Chancellor has been clear that that there will be more of the same in the October Budget, including on cutting welfare and investment.

There is no question that this amounts to another bout of austerity, following Thatcher’s original policies, which were later emulated by Cameron and Osborne.

But the question arises is why the government believes it will work this time around? After all, Einstein’s definition of madness is repeating the same experiment and expecting a different result.

It is worth restating that both previous bouts of austerity completely failed to generate growth and raise prosperity. Thatcher’s policies created an unemployment level of over 4 million people and was saved only by the sudden inflow of enormous North Sea oil revenues. Cameron and Osborne enjoyed no such windfall, with the result that living standards are no higher now than at the beginning of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-08.

This history holds important lessons for current policy. Both Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer have repeatedly claimed that their central economic aim is to raise the growth rate of the economy, and, from that raise average living standards and improve public services. But cuts have never delivered growth (Cameron and Osborne knew that and so started to increase public spending in 2014, ahead of the general election the following year).

The key to better public finances is growth, and anything that depresses GDP (including cuts to public spending and investment) will damage public finances. Under a previous Labour government, UK Treasury analysis codified this proposition, that growth reduces the deficit with the finding below:

“Overall a 1 per cent increase in output relative to trend after two years is estimated to reduce the ratio of public sector net borrowing to GDP by just under ¾ percentage point, while increasing the ratio of surplus on the current budget to GDP ratio by just under ¾ percentage point.” – Public Finances and Cycle, Treasury Economic Working Paper No.5, November 2008, (pdf).

In plain terms every £1 increase in GDP increases public sector receipts by over 50p, while also reducing public sector outlays by over 20p. The combined effect of the two is to improve government finances by 75p.

The government believes that growth is the answer to the current economic stagnation and is required for any improvement in public services. The conclusion of Treasury analysis points in the same direction. History shows too that prolonged bouts of austerity lower growth and mean that any improvement in public finances is extremely limited, at best.

A renewed austerity policy is in direct conflict with the stated aim of raising the growth rate.

Real and stated objectives

Massive job losses and/or real pay cuts, cuts to public services and welfare payments along with privatisations have not mainly been about public finances at all. When Callaghan/Healey first trialled them, it was claimed they were in response to a fictitious balance of payments crisis. Under Thatcher they were variously said to address money supply growth or inflation. It was only under Cameron/Osborne that the same policies were cast as addressing the (genuine) crisis of public sector finances.

When the same recipe is offered as a cure-all but is a remedy for none, it is reasonable to suggest that there is another, unstated motivation behind the policy. As these policies are combined with repeated cuts to taxes on profits, it is easy to see that the austerity policy is actually a transfer of incomes from poor to rich and from workers to businesses.

Profits are the motor force of a capitalist economy, especially an economy like Britain where so much of the economy is in the hands of the private sector. The aim of austerity is to fire up that motor by boosting profits. However, in practice that has been extremely difficult to enact, for a variety of reasons. Key among those has been the resistance of organised labour to real pay cuts.

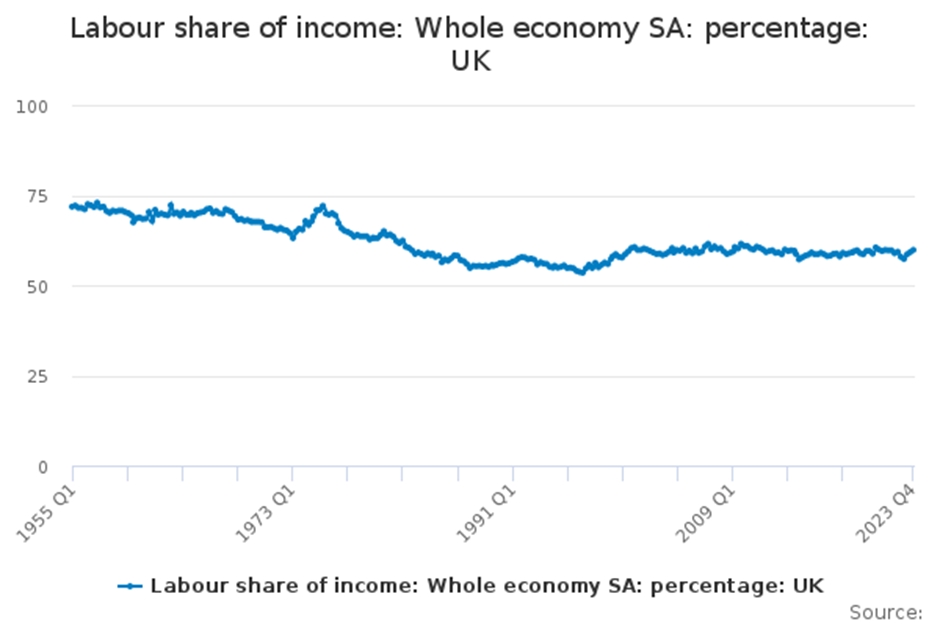

This is shown in the chart below.

Chart1. Labour share of national income, %

Source: ONS

Callaghan/Healey and then Thatcher had some success in driving down the labour share of national income and so raising the profit share. But there was a bounce-back after Britain was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1993 (which was another attempt to ‘force wage inflation out of the system’), and there it remained under Blair.

Cameron and Osborne later imposed vicious austerity and living standards have stagnated. But 14 years of austerity has produced a decline in the labour share of national income from 60.9% to 59.8% now. Put another way, austerity did shrink the growth rate of the economy towards zero and has decimated public services, but it has not remotely achieved its real objective of raising profits.

What are Starmer and Reeves hoping to achieve?

There is a fundamental departure in this initial phase of austerity under Labour compared previous episodes. There have already been small policy downpayments to cuts in investment, cuts to the infrastructure for public services and transport, as well as social welfare cuts and threats of privatisation in the form of debt-laden PFI.

Yet at the same time there are promises of pay rises above-current inflation in some parts the public sector, although it is not clear whether these will be funded with new money or from existing departmental budgets.

In some cases the suggested pay offers are way above the current rate of inflation. For example, 22% pay rises for junior doctors over 2 years may only be beginning to catch up with a loss of real pay over more than a decade. It may also be a huge exaggeration compared to what the substance of the offer is. But even if both are true, it completely contradicts all previous bouts of austerity.

In the drive to force wages down and profits up, previous governments have heavily relied on cuts or freezes to public sector pay. A variety of reasons have been given, but the aim is consistent. The public sector remains by far the biggest single employer in the country; it still employs almost 6 million workers. Austerity governments have attempted to use real pay cuts in the public sector to set a ‘going rate’ for the whole economy (economists’ jargon is a ‘demonstration effect’).

But this government has chosen a completely different course, and is supplementing inflation-plus pay rises with adjustments higher for the national minimum wage. This may even encourage pay rises in the private sector. It certainly will not depress them.

As a result, we could describe early Labour policy as social austerity, where cuts are focused on welfare spending and infrastructure. Both of these will prove highly damaging. But, for now, the new austerity does not seem to include wages in some parts of the public sector where there have been significant struggles.

Politically, there will clearly be the hope in government circles that unions will remain quiet in the face of cuts as long as pay is rising. Short-term, this could prove correct. It may allow the government to make dramatic changes to the role of the private sector in public services.

Ministers will surely hope that it will buy peace in key public services and put an end to industrial action. It should be noted that the industrial action itself has been a huge success in beating back efforts to slash real wages any keeping pay rises well below inflation. The multi-year success of the defensive action blocking real cuts to pay has now turned into a victory.

But economically it is incoherent and much-needed growth will not follow. Economic incoherence cannot be sustained.

Wages and public services can be improved through investment-led growth. Or wages too will come under the axe. One certainty is that this economic policy is unsustainable.

Recent Comments