Deng Xiaoping and John Maynard Keynes

By John Ross

Introduction

The international importance of China’s economy is twofold. The first is practical – the scale of China’s economic growth, its global impact, and the consequences for the improvement of the social conditions of China and the world’s population. The second is theoretical, including the potential international applicability of conclusions drawn from China’s economic policies.

Regarding the latter it is necessary to clearly state that no country can mechanically copy another. As China’s political leaders and economic theorists stress its economy has unique ‘Chinese characteristics’. This was formulated as a cardinal principle by the initiator of China’s economic reform, Deng Xiaoping: ‘To accomplish modernization of a Chinese type, we must proceed from China’s special characteristics.’ (Deng, 30 March 1979) Therefore China must: ‘blaze a path of our own.’ (Deng, 21 August 1985). As recently reiterated by Justin Yifu Lin, Chinese Chief Economist and Senior Vice President of the World Bank: ‘we can never be too careful when it comes to the application of a foreign theory, because with different preconditions, no matter how trivial they seem, the result can be very different.’ (Lin, 2012, pp. 66 – emphasis in the original) In that sense, therefore, there is no ‘Chinese model’. However as Lin simultaneously states: ‘Some may think that the performance of a country as unique as China, with more than 1.3 billion people, cannot be replicated. I disagree. Every developing country can have similar opportunities to sustain rapid growth for several decades and reduce poverty dramatically if it exploits the benefits of backwardness, imports technology from advanced countries, and upgrades its industries.’ (Lin, 2011)

There is, however, no contradiction between these different statements. The fundamental structural elements of which an economy is composed (consumption, investment, savings, primary industry, secondary industry, tertiary industry, trade, money etc.) are universal. However the particular way in which these elements combine and are interrelated in any economy is unique and entirely specific both in place and time – which is why no country can copy another’s economic policy, while it can learn from other economies. As analysed below, China has solved in practice problems stated in general macro-economic theory. For that reason such elements, in very different forms and combinations, are of major importance for economic policy elsewhere. However the specific forms and combinations in which such policies are applied are entirely unique both in each country and at different points in time.

The practical impact of China’s economic rise have been considered extensively elsewhere.1 The focus of this article is on the theoretical economic issues. In particular it aims to relate China’s economic performance to Western economic theory which will be more familiar to most readers.

China and macro-economic theory in Keynesian and Marxist terms

China’s ‘reform and opening up’ process under Deng Xiaoping was, of course, formulated in a Marxist economic framework. It can indeed be clearly outlined in those terms – see the appendix below, for a more detailed account of Chinese discussions on these issues see (Hsu, 1991), but an alternative statement in Western economic terms, those of Keynes, is considered here.

Stated briefly in Marxist terms, China’s reform policy included a critique of Soviet economic policy that this had made the error of confusing the ‘advanced’ stage of socialism/communism, in which the regulation of the economy is ‘for need’, and therefore not market regulated, with the socialist, or more precisely ‘primary’ developing stage of socialism, during which the transition from capitalism to an advanced socialist economy takes place and in which market regulation takes place. This transition should be conceived as extending over a prolonged period. The final formulation arrived at was that China’s was a ‘socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics’. Contrary to suggestions by some writers, for example (Hsu, 1991), such an analysis is in line with Marx’s own writings although, as shown below, it is not necessary to be a Marxist understand it – a more detailed analysis is given in the appendix.

This debate was framed in Chinese terms, without primary reference to previous economic theory in other countries other than Marx himself. The approach, in a Chinese phrase emphasised by Deng, was to ‘seek truth from facts’ (Deng, 2 June 1978). In practical terms in China, such analysis meant abandonment of an administratively planned economy and substitution of a market economy in which the state would control certain key macroeconomic parameters. In terms of ownership it led to ‘Zhuada Fangxiao’ – maintaining large state firms and releasing small ones to the non-state/private sector.

Restatement of Chinese economic policy in terms of Keynesian economics

Most people in the US and Europe are unaware of, or disagree with, Marxist economic categories. To make the essential economic policies clear, therefore, this article will put them in more familiar terms of Western economics – those of Keynes. The proviso is that this is the actual Keynes of The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money – not the vulgarised version in economics textbooks. Geoff Tily’s Keynes Betrayed (Tily, 2007) is one of the best in a series of works outlining the difference between the two.

However, there is no substitute for reading Keynes General Theory itself, which differs sharply from the presentation of what is frequently presented as ‘Keynesian’ economics. For example, budget deficits play only a secondary role in both Keynes General Theory and in China’s stimulus packages – even during 2009’s maximum anti-crisis measures China’ s budget deficit was only 3% of GDP. The core of Keynes’ General Theory itself, unlike vulgarisations, centres on factors determining investment. It is therefore through this optic that both Keynes and Chinese economic strategy can be best approached.

The rising proportion of the economy devoted to investment

In the founding work of classical economics, The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith identified division of labour as the fundamental force raising productivity, stating as the opening sentence of the first chapter: ‘The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgement with which it is any where directed, or applied, seems to have been the effects of the division of labour.’ (Smith, 1776, p. 13) Smith concluded that a necessary consequence of the increasing division of labour was that the proportion of the economy devoted to investment rose with economic development: ‘accumulation of stock must, in the nature of things, be previous to the division of labour, so labour can be more and more subdivided in proportion only as stock is previously more and more accumulated… As the division of labour advances, therefore, in order to give constant employment to an equal number of workmen, an equal stock of provisions, and a greater stock of materials and tools than what would have been necessary in a ruder state of things must be accumulated beforehand.’ (Smith, 1776, p. 277) A more comprehensive treatment of Smith’s views may be found in (Ross, 2011). Marx reached the same conclusion as Smith, concluding that the contribution of investment rose as an economy developed, which he termed the rising ‘organic composition of capital’ (Marx, 1867, p. 762).

Keynes similarly analysed that the proportion of the economy devoted to investment rose with economic development. His explanation was, however, somewhat different to Smith’s as Keynes rooted this in rising savings levels accompanying development. As the percentage of income consumed fell with increasing wealth, the proportion devoted to saving necessarily rose proportionately: ‘men are disposed… to increase their consumption as their income increases, but not by as much as the increase in their income… a higher absolute level of income will tend… to widen the gap between income and consumption.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 36) As total savings necessarily equals total investment, a rising proportion of saving therefore necessarily means a rising proportion of investment.

A necessary consequence of an increase in the proportion of the economy devoted to investment is that any investment decline will have increasingly serious consequences: ‘the richer the community, the wider will tend to be the gap between its actual and its potential production… For a poor community will be prone to consume by far the greater part of its output, so that a very modest measure of investment will be sufficient to provide full employment; whereas a wealthy community will have to discover much ampler opportunities for investment if the saving propensities of its wealthier members are to be compatible with the employment of its poorer members. If in a potentially wealthy community the inducement to invest is weak… the working of the principle of effective demand will compel it to reduce its actual output, until, in spite of its potential wealth, it has become so poor that its surplus over its consumption is sufficiently diminished to correspond to the weakness of the inducement to invest.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 31)

Failure of attempts to refute Keynes on the rising proportion of investment

In the mid-20th century attempts were made to dispute this conclusion of classical economics, originally deriving from Smith, of a rising proportion of investment in the economy – Milton Friedman devoted a book, A Theory of the Consumption Function, to attempting to refute Keynes on this (Friedman, 1957). However modern econometrics findings are conclusive in support of Smith and Keynes and against Friedman – the definitive demonstration, as frequently on matters of long term economic growth, being given by Angus Maddison. (Maddison, 1992) Factually, as classical economics and Keynes analysed, the trend is for the proportion of the economy devoted to investment to rise. To illustrate this, Figure 1 shows the percentage of fixed investment in GDP of the leading economies of successive periods of growth over the 300-year period for which meaningful statistics exist.

A reason Friedman attempted, unsuccessfully, to refute Keynes over the rising proportion of investment in the economy is that such a trend, as will be seen, is potentially destabilising – Friedman noted: ‘the central analytical proposition of the [theoretical] structure is the denial that the long-run equilibrium position of a free enterprise economy is necessarily at full employment.’ (Friedman, 1957, p. 237)

Effective demand

There is a parallelism between Keynes’s analysis and Marx’s regarding the role of profit and investment. The latter noted that without offsetting factors, a rise in the proportion of investment in the economy would led to a falling rate of profit as a necessary consequence of a rise in capital relative to the profits stream – i.e. Increasing division of labour, through its effect in raising investment as proportion of the economy, as analysed by Smith, created a tendency to a declining rate of profit (Marx, 1894, pp. 317-375).

Keynes also approached economic fluctuations via profit: ‘The trade cycle is best regarded… as being occasioned by a cyclical change in the marginal efficiency of capital.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 313) However, Keynes specific development was to approach the potentially destabilising consequences of the rising proportion of investment in the economy via effective demand.

Effective demand is composed of both consumption and investment, with the latter, as noted, tending to rise relative to the former over time. Keynes therefore noted: ‘when aggregate real income is increased aggregate consumption is increased but not by as much as income… Thus to justify any given amount of employment there must be an amount of current investment sufficient to absorb the excess of total output over what the community chooses to consume when employment is at the given level… It follows… that given what we shall call the community’s propensity to consume, the equilibrium level of employment, i.e. the level at which there is no inducement to employers as a whole either to expand or to contract employment, will depend on the amount of current investment.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 27)

Keynes noted no automatic mechanism ensures a necessary volume of investment to maintain effective demand: ‘the effective demand associated with full employment is a special case… It can only exist when, by accident or design, current investment provides an amount of demand just equal to the excess of the aggregate supply price of the output resulting from full employment over what the community will choose to spend on consumption when it is fully employed.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 28) Put aphoristically: ‘An act of individual saving means – so to speak – a decision not to have dinner today. But it does not necessitate a decision to have dinner or buy a pair of boots a week hence or a year hence.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 210). In more technical terminology: ‘The error lies in proceeding to the … inference that, when an individual saves, he will increase aggregate investment by an equal amount.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 83)

Any investment shortfall would be amplified by the well known economic ‘multiplier’ into much stronger cyclical fluctuations: ‘It is… to the general principle of the multiplier to which we have to look for an explanation of how fluctuations in the amount of investment, which are a comparatively small proportion of the national income, are capable of generating fluctuations in aggregate employment and income so much greater in amplitude than themselves.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 122) Such fluctuations in investment, combined with consumption, in turn determined employment: ‘The propensity to consume and the rate of new investment determine between them the volume of employment.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 30)

From this analysis Keynes derived key policy conclusions.

Budget deficits

One, well known, is countering recession with budget deficits, which Keynes dealt with as ‘loan expenditure’ – vulgarisation of Keynes lies in reducing his theories to support for budget deficits, not in the fact that he supported deficit spending. Keynes noted: ‘”loan expenditure” is a convenient expression for the net borrowing of public authorities on all accounts, whether on capital account or to meet a budgetary deficit. The one form of loan expenditure operates by increasing investment and the other by increasing the propensity to consume.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 128)

Therefore, in a famous passage: ‘If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines… and leave it to private enterprise… to dig the notes up again… with the help of repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater… It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 130)

Such a view of deficit spending naturally did not mean Keynes was indifferent to what deficits should be spent on – today environmentally sustainable investment would be added to his existing list. He had scathing contempt for double standards regarding when deficits were justifiable: ‘Pyramid-building, earthquakes, even wars… may serve to increase wealth, if… our statesmen… stands in the way of anything better… common sense… has been apt to reach a preference for wholly “wasteful” forms of loan expenditure rather than for partly wasteful forms, which because they are not wholly wasteful, tend to be judged on strict “business” principles. For example, unemployment relief financed by loans is more readily accepted than the financing of improvements at a charge below the current rate of interest…wars have been the only form of large-scale loan expenditure which statesmen have thought justifiable.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 129)

Interest rates

While Keynes supported deficit spending, the causes of recession lay in more fundamental factors affecting investment, which in turn were affected by interest rates: ‘the succession of boom and slump can be described and analysed in terms of the fluctuations of the marginal efficiency of capital relatively to the rate of interest.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 144) This was because marginal efficiency of capital was ‘equal to the rate of discount which would make the present value of the series of annuities given by returns expected from the capital-asset during its lift just equal to its supply price.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 135) Consequently, ‘inducement to invest depends partly on the investment-demand schedule and partly on the rate of interest.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 137)

As investment was affected by interest rates, therefore, a crucial issue to maintain investment at a sufficient level to sustain effective demand was a low interest rate. This problem, in turn, tended to become more acute because of the rising proportion of the economy devoted to investment: ‘Not only is the marginal propensity to consume weaker in a wealthy community, but owing to its accumulation of capital being already larger, the opportunities for further investment are less attractive unless the rate of interest falls at a sufficiently rapid rate; which brings us to the theory of the rate of interest and… reasons why it does not automatically fall to the appropriate levels.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 31)

The aim of low interest rates was to relaunch investment by ensuring that the return on investment was above the rate of interest plus whatever was the required premium to overcome liquidity preference. But, as Keynes openly acknowledged, such low term interest rates destroy the ability to live from income from interest – which is why, in his famous phrase, Keynes foresaw ‘euthanasia of the rentier.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 376) He concluded: ‘I see… the rentier aspect of capitalism as a transitional phase which will disappear.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 376)

‘A somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment’

Nevertheless, despite support for low interest rates Keynes, did not judge these would be likely by themselves to overcome the effects of an investment decline. It would therefore be necessary for the state to play a greater role: ‘Only experience… can show how far management of the rate of interest is capable of continuously stimulating the appropriate volume of investment… I am now somewhat sceptical of the success of a merely monetary policy directed towards influencing the rate of interest… I expect to see the State… taking an ever greater responsibility for directly organising investment.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 164) Consequently Keynes believed that regulating the level of investment would have to be undertaken by the state and not by the private sector: ‘I conclude that the duty of ordering the current volume of investment cannot safely be left in private hands.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 320) It was necessary, therefore, to aim at ‘a socially controlled rate of investment.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 325)

If, however, the state were to determine ‘the current volume of investment’ then this led Keynes to the conclusion: ‘It seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 378)

Keynes noted that this ‘somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment’ did not mean the elimination of the private sector, but socialised investment operating together with a private sector: ‘This need not exclude all manner of compromises and devices by which public authority will co-operate with private initiative… the necessary measures of socialisation can be introduced gradually and without a break in the general traditions of society… apart from the necessity of central controls to bring about an adjustment between the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest there is no more need to socialise economic life than there was before…. The central controls necessary to ensure full employment will, of course, involve a large extension of the traditional functions of government.’ (Keynes, 1936, p. 378)

The conclusion

It is now possible to clearly see the structure of Keynes’s argument. The rising proportion of the economy devoted to investment meant any downturn in the latter would have increasingly destabilising consequences. Budget deficits could deal with this to some degree, but as the key element was investment, which was determined by interaction between profits and interest rates, low interest rates was necessary. This would lead to the ‘euthanasia of the rentier’. However it was unlikely interest rates would be sufficient themselves and therefore the state would need to step in with ‘a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment’ which would however work alongside a private sector.

Tracing this argument one has now arrived at a ‘Chinese’ economic structure – although approaching it via a Keynesian and not a Marxist framework. ‘Zhuada Fangxiao’, grasping large state firms and releasing small ones to the non-state/private sector, coupled with abandonment of quantitative planning, means that China’s economy is not being regulated via administrative means but by general macro-economic control, including centrally of the level of investment – as Keynes advocated.

Implications

What is the overall significance of this? Deng Xiaoping’s most famous economic statement is ‘cats theory’ – ‘it doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white provided it catches mice’. But ‘cats theory’ can be applied to economics itself – it doesn’t matter whether something is described in Marxist or Western economic terms provided the same economic policies exist. ‘Zhuada Fangxiao’ may be arrived at from either a Keynesian or a Marxist framework.

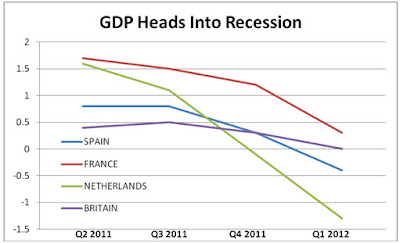

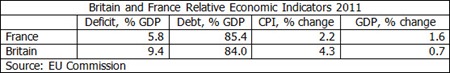

But while one may be indifferent to the colour of theoretical cats it is not possible to be indifferent as regards the policy measures to be taken – steps in budget deficits, interests rates, investment etc are material and precise. Here there is a radical difference in between the US and Europe on one side and China on the other.

In the US and Europe budget deficits have been utilised – although they are under increasing attack. Low central bank interest rates have been pursued and some forms of quantitative easing, driving down long term interest rates through central bank purchases of debt, have been used. But no serious programmes of state investment have been launched – let alone Keynes’s ‘somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment’.

In China, in contrast, relatively limited budget deficits have been combined with low interest rates, a state owned banking system (‘euthanasia of the rentier’) and a huge state investment programme. While the West’s economic recovery programme has been timid, China has pursued full blooded policies of the type recognisable from Keynes General Theory as well as its own ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics.’ Why this contrast and why has China’s stimulus package been so much more successful than the West’s?

Because in the US and Europe, of course, it is held that the colour of the cat matters very much. Only the private sector coloured cat is good, the state sector coloured cat is bad. Therefore even if the private sector cat is catching insufficient mice, that is the economy is in severe recession, the state sector cat must not be used to catch them. In China both cats have been let lose – and therefore far more mice are caught.

The recession in the Western economies, as foreseen by Keynes, is driven by decline in investment – in most countries decline in fixed investment accounted for two thirds to more than ninety per cent of the GDP fall (Ross, Li, & Xu, 2010). Keynes’s calls for not only budget deficits and low interest rates but also for the state to set about ‘organising investment’ are evidently required. But this is blocked because the state coloured cat is not allowed to catch mice.

To put it another way, the US and Europe insist on participating in a race while hopping on only one leg – the private sector. China is using two legs, so little wonder it is running faster.

To turn from metaphors to economic measures, a large scale state financed house building programme, or large scale expansion of transport, of the type China is following as part of anti-crisis measures not only delivers goods that are valuable in themselves but boosts the economy through macro-economic effects in raising investment. But in the West such state investment is blocked as it creates competition for the private sector. As the top aim in the US and Europe is not to revive the economy, but to protect the private sector, therefore such large-scale investment must not be undertaken.

It is an irony. Keynes explicitly put forward his theories to save capitalism. But the structure of the US and European economies has made it impossible to implement Keynes’s policies even when confronted with the most severe recession since the Great Depression. The anti-crisis measures of China’s ‘socialist market economy’ are far closer to those Keynes foresaw that any capitalist economy. Whereas in the US, for example, fixed investment fell by over twenty five per cent during the financial crisis in China urban fixed investment rose by over thirty per cent. Consequently, there is no mystery why China’s economy has grown by 41.4 per cent in the four years since the peak of the last US business cycle, in the 4th quarter of 2007, while the US economy has grown by 0.7 per cent.

Deng Xiaoping famously said his death was ‘going to meet Marx’. But Deng may also be having an intense talk with John Maynard Keynes. And Keynes would be interested to discuss with Deng’s two cats – who appear to have read the General Theory more closely and accurately than any administration in the West.

Put in more prosaic terms, China’s economic structure, because it allowed ‘a socially controlled rate of investment’ and a ‘somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment’, could utilise policy tools developed by Keynes but the US and European economies could not. Although Keynes explicitly wished to save capitalism it turned out that Western capitalism could not use his tools, but China’s ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ could. Deng Xiaoping could not fit in the framework of Keynes, but Keynes could fit rather neatly within the framework of Deng Xiaoping.

Appendix – the issues restated in Marxist terms

In the article above an account has been given of China’s macro-economic policy in terms of a theoretical framework derived from Keynes. Deng Xiaoping, however, as a Communist naturally explicitly formulated China’s economic policy in Marxist terms – China’s economic reform policies were seen as the integration of Marxism with the specific conditions in China. More precisely Deng stated: ‘We were victorious in the Chinese revolution precisely because we applied the universal principles of Marxism-Leninism to our own realities.’ (Deng, 28 August 1985) Consequently: ‘Our principle is that we should integrate Marxism with Chinese practice and blaze a path of our own. That is what we call building socialism with Chinese characteristics.’ (Deng, 21 August 1985)

Authors, including (Hsu, 1991), have contended that Deng’s economic policies were not in accord with those of Marx. However while China’s economic policies clearly differed from those of the USSR after the introduction of the First Five Year Plan in 1929, which introduced comprehensive planning and essentially total state ownership, it is clear that China’s economic policies were in line with those indicated by Marx. Whether people wish to formulate Chinese economic policy in Keynesian or Marxist terms may be left to them. What is most crucial is not the colour of the cat but whether it catches mice – that is, the practical policy conclusions drawn. This appendix therefore briefly shows that Deng’s essential concepts in launching China’s economic reform in in 1978 corresponded to Marx’s.

The primary stage of socialism

Regarding China’s economic reform policies Deng noted, as stated in Marxist terms, that China was in the socialist and not the (higher) communist stage of development. Large scale development of the productive forces/output was the prerequisite before China could make the transition to a communist society: ‘A Communist society is one in which there is no exploitation of man by man, there is great material abundance, and the principle of from each according to their ability, to each according to his needs is applied. It is impossible to apply that principle without overwhelming material wealth. In order to realise communism, we have to accomplish the tasks set in the socialist stage. They are legion, but the fundamental one is to develop the productive forces.’ (Deng, 28 August 1985) More precisely, in a characterisation maintained to the present, China was in the ‘primary stage’ of socialism, which was fundamental in defining policy: ‘‘The Thirteenth National Party Congress will explain what stage China is in: the primary stage of socialism. Socialism itself is the first stage of communism, and here in China we are still in the primary stage of socialism – that is, the underdeveloped stage. In everything we do we must proceed from this reality, and all planning must be consistent with it.’ (Deng, 29 August 1987)

The fundamental characterisations by Deng have been maintained to the present – thus for example in July 2011 President Hu Jintao stressed that ‘China is still in the primary stage of socialism and will remain so for a long time to come’ (Xinhua, 2011), while speaking to the UN premier Wen Jiabao noted ‘Taken as a whole, China is still in the primary stage of socialism’ (Xinhua, 2010). The conclusion flowing from this as noted by Hsu, was that: ‘From this perspective, a serious error in the past was the leftist belief that China could skip the primary stage and practice full socialism immediately.’ (Hsu, 1991, p. 11)

The conclusion of such a contrast between a primary socialist stage of development and and the principle of a communist society (which, as noted by Deng above, was regulated by ‘from each according to their ability to each according to each according to his needs’) was that in the present ‘socialist’ period the principle was ‘ to each according to their work’: ‘We must adhere to this socialist principle which calls for distribution according to the quantity and quality of an individual’s work.’ (Deng, 28 March 1978) In Marxist theory, outlined by Marx in the opening chapter of Capital (Marx, 1867), economic distribution according to work/labour is the fundamental principle of commodity production – and a commodity necessarily implies a market. In this socialist period a market would therefore exist – hence the eventual Chinese terminology of a ‘socialist market economy.’ As presented by Deng Xiaoping and his successors above such Chinese analysis is highly compressed but clearly in line with Marx himself.

It is clear Marx envisaged that the transition from capitalism to communism would be a prolonged one, noting in The Communist Manifesto: ‘The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.’ (Marx & Engels, 1848, p. 504) The ‘by degree’ may noted – Marx therefore clearly envisaged a period during which state owned property and private property would exist. China’s system, after Deng, of simultaneous existence of sectors of state and private ownership is therefore clearly more in line with Marx’s conceptualisation than Stalin’s introduction ‘all at once’ of essentially 100 per cent state ownership in 1929.

Regarding Deng’s formulations on communist society being regulated by ‘to each according to their need’ versus the primary stage of socialism regulated by ‘each according to their work’ Marx noted in the Critique of the Gotha Programme of the post-capitalist transition to a communist society: ‘What we are dealing with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society, which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birth-marks of the old society from whose womb it emerges.’ (Marx, 1875, p. 85)

In such a transition Marx outlined payment in society, and distribution of products and services, necessarily had to be ‘according to work’ even within the state owned sector of the economy:‘Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society – after the deductions have been made – exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labour. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labour time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labour (after deducting his labour for the common funds); and with this certificate, he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labour cost. The same amount of labour which he has given to society in one form, he receives back in another.

‘Here obviously the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is exchange of equal values…. as far as the distribution of the latter among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labour in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labour in another form.

‘Hence, equal right here is still in principle – bourgeois right… The right of the producers is proportional to the labour they supply; the equality consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labour.’ (Marx, 1875, p. 86)

In such a society inequality would necessarily still exist: ‘one… is superior to another physically or mentally and so supplies more labour in the same time, or can labour for a longer time; and labour, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labour… it tacitly recognises the unequal individual endowment and thus the productive capacities of the workers as natural privileges. It is, therefore, a right of inequality in its content like every right. Right by its very nature can consist only as the application of an equal standard; but unequal individuals (and they would not be different individuals if they were not unequal) are measurable by an equal standard only insofar as they are made subject to an equal criterion, are taken from a certain side only, for instance, in the present case, are regarded only as workers and nothing more is seen in them, everything else being ignored. Besides, one worker is married, another not; one has more children than another, etc. etc.. Thus, given an equal amount of work done, and hence an equal share in the social consumption fund, one will in fact receive more than another, one will be richer than another, and so on. To avoid all these defects, right would have to be unequal rather than equal.’ (Marx, 1875, pp. 86-87)

Marx considered only after a prolonged transition would payment according to work be replaced with the ultimately desired goal, distribution of products according to members of society’s needs.

‘Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development which this determines.

‘In a higher phase of communist society… after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of common wealth flow more abundantly – only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs!’ (Marx, 1875, p. 87)

It is therefore clear that post-Deng policies in China were more in line with Marx’s prescriptions than post-1929 Stalin policies in the USSR. Given the essentially 100 per cent state ownership of industry in China in 1978 ‘Zhuada Fangxiao’ – maintaining the large enterprises within the state sector and releasing the small ones to the non-state sector – together with the creation of a new private sector created an economic structure clearly more in line with that envisaged by Marx than the essentially 100 per cent state ownership in the USSR after 1929. Deng’s insistence on the formula that in the transitional period reward would be ‘according to work’ and not ‘according to need’ was clearly in line with Marx’s analyses. It is notable that in the USSR itself a number of economists opposed Stalin’s post-1929 policies on the same or related grounds – including Buhkarin (Bukharin, 1925) , Kondratiev (Kondratiev), Trotsky (Trotsky, 1931) and Preobrazhensky (Preobrazhensky, 1921-27) (Preobrazhensky, 1921-27). Their works were, however, almost unknown as these issues were ‘resolved’ by Stalin killing those economists who disagreed with him and banning their works – although several accounts have been published outside the USSR – see for example (Jasny, 1972) (Lewin, 1975). China’s economic debates therefore appear to have preceded with reference to China’s conditions and Marx and not any preceding debates in the USSR.

It is therefore clear that China’s post-reform economic policy is in line with Marx’s analysis and that, as stated in Chinese analysis, post-1929 Soviet policy departed from Marx’s analysis – the argument that the converse is true, by Hsu and others, is invalid.

As China’s economic policy and structure can be understood in either Keynesian or Marxist terms it is a more general issue which is to be preferred. ‘It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white provided it catches mice’ might appear an appropriate response.

This aritcle originally appear on Key Trends in Globalisation. An earlier and shorter version article appeared in Soundings.

Notes and Bibliography

1. In the last twenty-five years China has lifted more than 620 million people out of absolute poverty. That is, according to the calculations of Professor Danny Quah of the London School of Economics, 100% of the reduction in the number of those living in absolute poverty in the world. (Quah, 2010) No other country remotely compares to China’s contribution to the reduction of world poverty – a fact placing legitimate, and illegitimate, criticism of China in an appropriate qualitative context.

It is sometimes mistakenly argued that rapid economic growth in China has not aided consumption. This is an economic error – it confuses the percentage of consumption in GDP, which is low in China compared to other economies, with China’s rate of growth of consumption – which is the highest of any major country (see Table 1). The reason China has the fastest rate of growth of consumption in any major economy is because it has the fastest rate of GDP growth – in all economies the growth rate of GDP is highly correlated with the growth rate of consumption.

The result of these trends is that the IMF estimates that in Parity Purchasing Power (PPP) terms, China’s will become the largest economy in the world in 2016. At market prices China’s GDP is likely to become the world’s largest in 2018–2019. (Ross, 2011e) (The Economist, 2011)The widely quoted Goldman Sachs estimate that China’s GDP would overtake the US, at official exchange rates, in 2026 was made before the financial crisis and is outdated.

Bibliography

Bukharin, N. (1925). ‘Critique de la plate-forme économique de l’opposition’. In L. Trotsky, E. Préobrajensky, N. Boukharine, Lapidus, & Osttrovitianov, Le Débat Soviétique Sur La Loi de La Valeur (1972 ed., pp. 201-240). Paris: Maspero.

Deng, X. (28 March 1978). ‘Adhere to the principle “to each according to his work’. In X. Deng, Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping (2001 ed., pp. 117-118). Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific.

Deng, X. (2 June 1978). ‘Speech at the all-army conference on political work’. In X. Deng, Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping 1975-1982 (2001 ed., pp. 127-140). Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific.

Deng, X. (30 March 1979). ‘Uphold the Four Cardinal Principles’. In 2001 (Ed.), Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping 1975-1982 (pp. 166-191). Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific.

Deng, X. (21 August 1985). ‘Two kinds of comments about China’s reform’. In X. Deng, Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping 1982-1992 (1994 ed., pp. 138-9). Foreign Languages Press.

Deng, X. (28 August 1985). ‘Reform is the only way for China to develop its productive forces’. In X. Deng, Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping 1982-1992 (pp. 140-143). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

Deng, X. (29 August 1987). ‘In everything we do we must proceed from the realities of the primary stage of socialism’. In X. Deng, Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping 1982-1992 (pp. 247-8). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

Friedman, M. (1957). A Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hsu, R. C. (1991). Economic Theories in China 1979-1988. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jasny, N. (1972). Soviet Economists of the Twenties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (Macmillan 1983 ed.). London: Macmillan.

Kondratiev, N. D. (n.d.). The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (1998 ed.). (N. Makasheva, W. J. Samuels, V. Barnett, Eds., & S. S. Williams, Trans.) Pickering and Chatto.

Lewin, M. (1975). Political Undercurrents in Soviet Economic Debates. London: Pluto Press.

Lin, J. Y. (2011, December 22). ‘Demystifying the Chinese Economy’. Retrieved December 25, 2011, from Project Syndicate: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/lin5/English

Lin, J. Y. (2012). Demystifying the Chinese Economy. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maddison, A. (1992). ‘A Long Run Perspective on Saving’. Scandanavian Journal of Economics, 94(2), 181-196.

Marx, K. (1867). Capital Vol.1 (1988 ed.). (B. Fowkdes, Trans.) Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, K. (1875). ‘Marginal notes on the programme of the German Workers Party’. In K. Marx, Karl Marx Frederich Engels Collected Works (1989 ed., Vol. 24, pp. 81-99). London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Marx, K. (1894). Capital Vol.3 (1981 ed.). (D. Fernbach, Trans.) Harmondworth, UK: Penguin.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). ‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’. In K. Marx, & F. Engels, Collected Works (1976 ed., Vol. 7, pp. 476-519). London, UK: Lawrence and Wishart.

Preobrazhensky, E. (1921-27). The Crisis of Soviet Industrialization (1980 ed.). (D. A. Filzer, Ed.) London: MacMillan.

Preobrazhensky, E. (1926). The New Economics (1967 ed.). (B. Pearce, Trans.) Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Quah, D. (2010, May). ‘The Shifting Distribution of Global Economic Activity’. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from London School of Economics: econ.lse.ac.uk/~dquah/p/2010.05-Shifting_Distribution_GEA-DQ.pdf

Ross, J. (2011, June 22). ‘Why Adam Smith’s ‘classical theory’ correctly explained Asia’s growth – and how this clarifies why Paul Krugman’s critique of Asian growth failed to predict events’. Retrieved June 22, 2011, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2011/06/adam_smith.html

Ross, J. (2011e, February 15). ‘The central date for China’s GDP to overtake the US at market exchange rates is 2019 – a study of growth assumptions and analyses’. Retrieved February 23, 2011, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2011/02/the-central-date-for-china.html

Ross, J., Li, H., & Xu, X. C. (2010, June 29). ‘The Great Recession’ is actually ‘The Great Investment Collapse’ . Retrieved July 30, 2010, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2010/06/the-great-recession-is-actually-the-great-investment-collapse-by-john-ross-li-hongke-and-xu-xi-chi.html

Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1981 ed.). Liberty Edition Volume 1.

The Economist. (2011, December 2011). ‘How to get a date’. Retrieved January 3, 2012, from The Economist: http://bit.ly/uDEC0N

Tily, G. (2007). Keynes’s General Theory, the Rate of Interest and ‘Keynesian’ Economics. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Trotsky, L. (1931). ‘The New Course in the Soviet Economy – An Adventure in Economics and Its Dangers’. In L. Trotsky, Writings of Leon Trotsky 1930 (1975 ed., pp. 105-119). New Yorkk: Pathfinder.

Xinhua. (2010, September 24). ‘Premier Wen expounds ‘real China’ at UN debate’. Retrieved February 2, 2012, from China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010WenUN/2010-09/24/content_11340091.htm

Xinhua. (2011, July 1). ‘China still largest developing country: Hu’. Retrieved February 2, 2012, from China Daily: http://www2.chinadaily.com.cn/china/cpc2011/2011-07/01/content_12817816.htmT Walkerhttps://www.blogger.com/profile/11107827543023820698noreply@blogger.com0

Recent Comments