Why More ‘Austerity’ Is On the WayBy Michael Burke

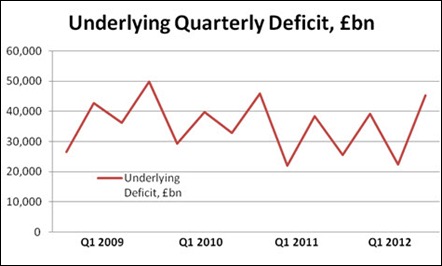

The latest monthly public borrowing data, which show a large deficit in government finances, have widely been hailed as a ‘surprise’. However, SEB has previously pointed out that the deficit has been widening over the prior six months, so that the latest shortfall in government finances is simply the continuation of an established trend.

More fundamentally, it does not require very sophisticated economic analysis to assume that a renewed contraction in the economy will lead to both higher government spending and lower government tax receipts. Despite higher prices, the nominal level of taxation receipts has fallen since the beginning of 2012, and expenditures have risen. At the very least, the borrowing data should put paid to all the chatter that the GDP data showing economic contraction is somehow wrong . Of course, the GDP data is subject to revision, like almost all economic releases including the data on public borrowing. But it is in practice inconceivable that the economy could be expanding while a significant shortfall appears in government finances. In that sense, government borrowing data are some of the most reliable of all, as they represent real expenditure made and income directly received by the government, rather than survey evidence and estimates of activity in the private sector.

International Experience

If there is any genuine ‘surprise’ from the widening in the budget deficit it is a product of an entirely incorrect framework that assumes that the state is an obstacle to economic prosperity and that removing it will boost output. In fact, the performance of the British economy and government finances in response to ‘austerity’ supports the opposite contention; which is that the state should be the leading force in an economy because it is more efficient than the private sector in developing economic growth. Reducing the weight of the state in the economy therefore damages economic activity.

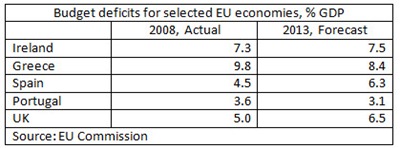

But anyone who has followed the trajectory of the crisis-hit European economies in the recent period would not at all be surprised by the outcome in Britain. In every case where severe ‘austerity’ measures have been put in place, economic activity has contracted. This has also usually been accompanied by no significant improvement in projections for government finances, and in some cases a deterioration. The table below shows the EU Commission estimates and forecasts for the budget deficits in selected EU economies. It should be stressed that these are the EU Commission’s forecasts (in the Spring 2012 Euro Area Economic Forecasts), and have in the past been subject to negative revisions.

Policy Response

The response to economic contraction and renewed widening in government budget deficits in the crisis countries of the EU is also instructive. In none of these cases has there been a reversal of policy, so allowing growth and therefore an improvement in government finances. Greece and Portugal largely had austerity foisted on them by the Troika of the EU, IMF and ECB. Spain, like Britain, initially had a mildly stimulative policy carried out by governments of the left, PSOE and the Labour Party respectively. However, while this partly reversed the slump it was wholly insufficient to provide economic recovery and they then switched to ‘austerity’ policies. This appeared to the electorate like an inconsistent and illogical zigzag on economic policy and ushered in parties of the right even more committed to an attack on the living standards of workers and the poor.

Ireland was a different case, as its ruling circles are wholly committed to the interests of foreign capital and their domestic agents (in this case, the speculators of Allied Irish Bank and its manly foreign bondholders). Therefore, without any external political impositions, the Irish government moved straight to an ‘austerity’ policy of its own. It later fell into the clutches of the Troika simply because this policy had utterly failed. The Troika then loaded the Irish state with even more debt in order to extend the policy.

Britain is unlikely to be any different and ‘austerity’ will be deepened. Reports of the latest deficit widening had headlines such as ‘Surprise deficit raises risk of more austerity , and ‘Tax slump threatens to set off new wave of cuts’ .

Even prior to the UK borrowing data, a series of business calls had been raised for further cuts in welfare payments in order to provide investment subsidies for firms. The Institute of Directors, the CBI and the British Chambers of Commerce have all been plugging deregulation and tax ‘reform’ as well spending cuts. This is actually an agenda for lower employment rights, safety and environmental standards, as well as tax cuts for corporations at the expense of labour and the poor. That is, a deepening of ‘austerity’.

Rationale of Policy

Rhetorically, it is possible to speak of the classic definition of the ‘madness’ of current policy in Einstein’s sense; repeating an experiment and expecting a different outcome. But in truth the dynamic of current policy is not irrational at all. Just as in the rest of Europe, policy is not aimed at restoring growth at all, or even reducing the deficit, despite government claims to the contrary.

In any capitalist economy investment falls not because there is insufficient demand – the 1.8 million households on waiting lists for social housing in England could testify to that. Investment falls because capital cannot be invested for a sufficient profit. In Britain investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) began to decline in the 1st quarter of 2008, one quarter before GDP began to contract. It led the economy into recession and now accounts for 80 per cent of the total loss in output.

The purpose of current ‘austerity’ policy is to restore profits. Seen from the point of view of capital, there are two main current economic problems. The first is to reverse the adverse change in the profit share which takes place during recessions. The second is to create conditions allowing an increase in the profit rate.

1.In a recession the profit share falls. Company A produces goods which it sells for £1mn. It has wage costs of £0.5mn and other variable costs (raw material, energy, etc.) of £0.2mn. The surplus generated is £0.3mn. But in a recession it can only sell goods for £0.8mn as some are left unsold and some others offered at a discount. The costs of raw materials are almost entirely outside their hands. Faced with the same wages and raw material costs, the surplus falls to £0.1mn. This is exactly what has happened in the British economy since 2008. In nominal terms the compensation of employees had risen from £773bn to £816bn. Of course, in real terms, after inflation, there has been a marked decline in wages but in official data the distribution of incomes is presented only in nominal terms. But the gross operating surplus (GOS) of firms (akin to the surplus identified above) has risen from £503bn to just £508bn over the same period. Again, in real terms there has been a marked fall in the surplus. Crucially, the nominal rise in compensation has been greater than the rise in the surplus. Capital’s share in national income has declined as a result.

If Company A can lay off workers or cut overtime and maintain output it will do so in order to restore profits. But the complexity of the production process may not allow a significant reduction in wages with unchanged output. There is also the concern that a rival firm might increase its output and win market share from Company A, or even hire the workers it has trained. Instead, Company A will benefit if government can find a way to cut wages, say, by increasing the numbers of people unemployed in an attempt to force down wages, or cutting non-wage benefits to force those in work to work longer for less.

2.The cause of deep recessions is a decline in investment. Individually, firms are unwilling to resume investment until they can be much more certain of making adequate profits. In aggregate, they hoard capital and refuse to invest it. To make a profit Company A must deploy capital. This is in the form of both its costs of employment, raw materials and other input costs, as well as its costs of plant, machinery and so on. The rate of profit is the surplus extracted as a proportion of this total capital employed.

Frequently, boom precedes recession. This is not become economics is some kind of morality tale about excess, but because the boom includes an unusually high level of investment. In Britain, ‘unusually high’ is still weak by international standards but it meant the level of investment rose by 15 per cent in the four years to 2005, and by the same proportion again in the two years to 2007. This latter increase in the capital stock (plant, machinery, etc) took place while wages were growing but was not accompanied by an equivalent rise in the growth of the surplus. In fact, investment rose at a faster rate than the surplus. Since the profit rate is the ratio of the surplus versus total capital employed (both fixed capital and variable capital) and the surplus rose at a slower rate than investment, it follows that the profit rate fell.

But Company A is operating in a recession and sales are not rising and it cannot do anything about the costs of its plant and equipment. It is also at the mercy of market forces in terms of input costs such as raw materials. To restore the profit rate therefore requires a reduction in wages.

Anything which indirectly supports the level of wages such as benefit entitlements, unionisation, national pay bargaining, employment rights and so, must all come under attack to achieve this. Meanwhile, it will demand from government both that corporate tax rates must be cut and that the government provides work, or at least subsidies to it in order to boost sales and increase retained (after tax)profits.

This is the content of all ‘austerity’ policies. It is why they will continue even while growth is at best stagnant and the deficit rises once more. Policy is not aimed deficit reduction or still less economic well-being via growth. The aim of policy is restore and raise profits. It is why these policies will not only continue but deepen in the face of both economic contraction and a rising deficit.

The alternative remains large-scale state investment which will produce economic recovery. Firms wishing to survive will be obliged to participate in the recovery by investing on their own account, even at the lower profit rate.

Both resisting the impositions of further austerity and demanding the state lead the recovery through investment are the subject of a struggle between classes. Effectively it is a struggle about which major class will be forced to pay for resolving the crisis.

Recent Comments