.833ZThe central date for China’s GDP to overtake the US at market exchange rates is 2019 – a study of growth assumptions and analyses

By John Ross

Summary

The question of when China’s GDP will overtake the US, to become the world’s largest national economy, is self-evidently significant.1 It has become much discussed among Western economic commentators (Rachman, 2011).

When Goldman Sachs first suggested that China’s GDP would exceed that of the US by 2041 this caused surprise (Wilson & Purushothaman, 2003). When Goldman Sachs revised this forward to 2027 this caused greater shock (O’Neill, 2009). But it has since become evident that, on current trends, Goldman Sachs forecasts projected too long a period for China’s GDP to overtake the US – and did so before the international financial crisis.

In the last two years, work carried out by the present author in the Research Group China in the International Financial Crisis, at Antai College, Shanghai Jiao University, arrived at an estimate of the most central date for China’s GDP, at market exchange rates, to exceed the US as being 2019 – there is inevitably a degree of variance on either side in such projections.

Interestingly, as noted below, other recent analyses now arrive at essentially the same date range regarding parity purchasing power (PPP) estimates. A remaining weakness in a number of these latter studies, however, is that they have in the past underestimated China’s growth and still project too long a time scale for China’s GDP to equal the US at market exchange rates. The reasons for this are considered in detail below.

Perhaps surprisingly, it turns out that projections on this issue are not highly sensitive to the ranges of precise growth rates utilised – provided that these are within realistic historical bounds. The central conclusion is that, unless there is a qualitative change in the economic situation, China’s GDP at market prices is likely to exceed the US in the period 2017-2021. It is also significant that the rate of growth of US current dollar GDP is decreasing while the rate of growth of China’s dollar GDP is accelerating – purely linear projections therefore tend to overestimate the period of time before which China’s GDP equals that of the US.

This article surveys literature on this issue, clarifies the reasoning for such time frames, and analyses their key parameters. A fundamental qualitative characterisation of the relative position of the US and China’s GDPs is indicated.

Calculations on the range of reasonable US GDP growth rates to be projected have been considered in detail in other articles and these are utilised below.2 Concentration in this article is therefore on reasonable projections of the growth rate of China’s GDP in dollar terms.

Background – systematic underestimation of the growth rate of China’s economy

In any subject, including economics, the ultimate test of analysis and theory is how accurately it predicts developments. Therefore the two fundamental tests of analysis regarding former planned economies have been the success of China’s reform policy and the failure of shock therapy in Russia and the former USSR. The former produced the most rapid growth in any major economy, and the latter saw the greatest peacetime decline in production in any major country in modern history.

In both cases majority conventional wisdom at the time transpired to be incorrect. When in 1992 the present author contrasted favourably the success of China’s economic reform to the ‘shock therapy’ then being introduced in Russia, and predicted continued rapid economic growth in China compared to negative results in Russia, majority opinion disagreed with such analysis (Ross, 1992). However, at that time, China’s economy at market exchange rates was only 6.7 per cent the size of the US and only 67.5 per cent the size of the former USSR (World Bank, 2010). Therefore understanding of the potential of China’s economic policy was primarily based on issues of economic theory, related to the early progress of its economic reform, and not to the level of realised accomplishment which now prevails. Study of China’s economy in 1992 was also a minority interest, with the fashionable focus of attention at that time being the alleged benefits of shock therapy and with a prevailing view that China would lag because of its failure to adopt this.3

Nineteen years later the results are evident. China’s economy is the world’s second largest. It has maintained the highest rate of growth of any major economy throughout the almost two decade intervening period. Attention to China’s economy is no longer based primarily on potential or economic theory but on accomplished achievement. For comparison China’s economy today is almost three times as large as the economy of the entire former USSR, more than four times as large as the economy of Russia, and has overtaken Japan to become the world’s second largest. The relevant discussion now is when its GDP will overtake the US – hence this article.

Analysis of China’s economy has now also become highly fashionable and no longer of minority interest. Nevertheless, as will be shown below, many of the most widely cited predictions regarding China’s economy – for example those of Goldman Sachs and PWC – have underestimated how fast China’s economy would develop and have therefore regularly upgraded their forecasts. This error has still not been fully corrected. Most forecasters now project that China’s GDP will exceed that of the US in PPP terms during the next 10-20 years – with the majority of such projections falling towards the early part of this range. But, for reasons considered in detail, they continue to underestimate how rapidly China’s GDP will equal that of the US at market exchange rates.

The relevant literature will therefore first be surveyed and then a detailed examination will be made of the assumptions involved in projections of the size of China’s GDP compared to the US at market exchange rates.

Recent projections on China’s economic growth

Goldman Sach’s projection for China’s GDP to overtake the US in 2041, made in the well known paper ‘Dreaming with BRICs’, was based on the assumption that China’s GDP in nominal dollar terms, rather than at constant prices or exchange rates, would increase at 8.1 per cent a year between 2005 and 2040 (Wilson & Purushothaman, 2003).4 This projection turned out to be less than half the relevant rate of China’s growth in the last 10 years to 2010 – the actual outturn, in current dollars, was 17.2%. Jim O’Neill, former chief economist of Goldman Sachs, was therefore correct to note: ‘What many casual observers of our BRIC projections never realized is that we used extremely conservative assumptions.’ (O’Neill, 2009b) Unsurprisingly, therefore, Goldman Sachs, subsequently brought forward their projection of the year China’s GDP will overtake the US – to 2027 (O’Neill & Stupnytska, 2009). A further analysis of Goldman Sachs projections is given below.

More recent projections by others have calculated significantly earlier dates than Goldman Sachs. In the most extreme estimate Arvind Subramanian, of the Peterson Institute of International Economics, argues that in PPP terms, China has already overtaken the US (Subramanian, 2011). The Conference Board, estimates China’s GDP, again in PPP terms, could overtake the US in 2012 (The Conference Board, 2011). The current projection of the IMF in PPP terms is that China’s GDP will overtake the US shortly after 2015 (International Monetary Fund, 2010). The Economist projects China will overtake the US in 2019 (The Economist, 2010). PWC conclude China’s GDP will overtake the US before 2020 (Hawksworth, 2010) (Hawksworth & Tiwari, 2011). Standard Chartered bank predicts China will overtake the US by 2020 and that by 2030 its economy will be twice the size of the US (Adam, 2010)

In contrast, China’s media has tended to take a highly cautious approach to this issue – insisting that comparisons be made only in current exchange rates and utilising relatively optimistic projections regarding the US’s growth and relatively pessimistic ones regarding China’s (China Daily, 2010).

This echoes the Chinese media’s similar approach to comparisons of China’s economy with Japan. Calculations made in terms of PPPs showed that China overtook Japan to become the world’s second largest economy in 2001 (International Monetary Fund, 2010). China, however, only acknowledged that it was the world’s second largest economy in 2010, when it overtook Japan in current exchange rate terms.

In one sense such caution by China’s media is well founded. Serious issues need objective consideration. Exaggeration of achievements is unhelpful. Furthermore, as is well known, even when China’s GDP is the same as that of the US, China will still be a far poorer country in terms of income per person – to be precise, as China has approximately four times the population of the US, when China’s total GDP equals that of the US China’s GDP per capita will only be one quarter that of the US.

Nevertheless, while conservatism in assumptions is commendable, distortions in perspective and policy also occur if underestimates are made. The only really useful calculations are those which are accurate as regards fundamentals. Given that it is spurious exactitude on such a complex issue to give a single precise date it is necessary to analyse the key parameters involved and therefore the reasonable range of projections.

Official exchange rate and PPP studies

As is well known there exist two fundamental measures for estimating the relative sizes of the US and China’s economies – those made at market exchange rates and those made in terms of PPPs. Some studies, notably those carried out for PWC, analyse both. (Hawksworth, 2006) (Hawksworth & Cookson, 2008) (Hawksworth & Tiwari, 2011).

Both measures and approaches are relevant.5 However because market exchange rates are more objectively verifiable, because actual transactions are carried out in these terms, and because the Chinese authorities themselves generally only utilise calculations in market exchange rates, emphasis in this paper is on this measure. First however, to set parameters, literature utilising PPPs will be compared to those for the US and China’s GDP at market exchange rates.

Official exchange rate and PPP calculations

Calculations of the relative size of the US and China’s GDP at market exchange rates are simple and up to date. China has released its first official estimate of GDP in 2010 – 39.8 trillion yuan (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2011). No official exchange rate for conversion of this annual GDP to dollars was published, but utilising a simple unweighted daily average for 2010 yields a figure of $5.9 trillion – the final data will not differ greatly from this.6 This compares to a US GDP in 2010 of $14.7 trillion.7 (Bureau of Economic Research, 2010). At official exchange rates, China’s economy is approximately 40 per cent of the size of the US.

PPP calculations start from the well known fact that average prices in China, as with most developing countries, are lower that average prices in the US when converted at market exchange rates. The real comparative size of China’s GDP, in terms of real inputs and outputs, is therefore understated compared to the US,. It is for this reason that analysts have supplemented, or replaced use of, market exchange rates and attempted to calculate PPPs for China, the US and other economies.8

Nevertheless a drawback of this approach remains that the calculation made for PPP exchange rate is crucial for the estimate of the relative size of the two economies compared to market exchange rates – which in contrast are readily objectively verifiable. As will be seen, estimates based on calculated PPP’s therefore may yield very early dates for when China’s GDP will exceed the US.

Three PPP estimates of China’s GDP

Taking an overall review of the range of PPP estimates for the size of China’s economy three calculations essentially coincide – those of the World Bank, the IMF (International Monetary Fund, 2010) and the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency, 2011). Taking 2009, the latest date available for PPPs:

- the World Bank estimates the size of China’s GDP at $ 9091bn;

- the IMF estimates the size of China’s GDP at $9047bn;

- the CIA estimates the size of China’s GDP at $8950bn.

All, for 2009, therefore give a PPP estimate of the size of China’s GDP at 63-64 per cent of the US’s $14 256bn.

These figures are essentially calculated from the baseline estimate of the size of China’s GDP in PPPs in 2005 published by the World Bank International Comparison Programme (World Bank, 2007). This revised downwards the previous estimate of the size of China’s GDP by 40 per cent. This downward revision has, however, been contested by a number of authors on various grounds – for example that that backward projections of the data yield implausible results, or that basing price calculations only on cities yields inaccurate results as prices are lower in China’s rural areas (Deaton & Heston, 2008) (Subramanian, 2011).

Higher PPP estimates of China’s GDP

There therefore exist, for the above and other reasons, higher estimates of China’s GDP in PPP terms. The most extreme, as noted, are Subramanian’s, who argues that in these terms, China’s GDP is $14.9 trillion, and has already marginally overtaken the US (Subramanian, 2011). Subramanian, however, is an outlier in such estimates whose conclusions have not received any widespread support.

More significant, and more frequently quoted, are estimates by The Conference Board and those in the data of Angus Maddison – the Conference Board’s Total Economy database is now widely cited and Maddison was not only a leading authority on economic growth in general but made specific analyses of China’s GDP (Maddison, 1998) (Maddison & Wu). Regarding these:

- The Conference Board gives an estimate of $12.9 trillion for China’s GDP in PPP terms in 2010, compared to $14.5 trillion for the US, producing an estimate that China’s economy is already 89 per cent of the size of the US.

- Maddison died in 2010 and the latest year for which he gave estimates of the GDP of the US and Chinese economies was 2008. His calculations were expressed as 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars. Maddison’s base year was 1990, for which he calculated China’s GDP as $2124bn. Maddison’s views were emphatic, for reasons stated in detail in his Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, and his conclusion was already that: ‘In 2003 its [China’s] GDP was about 73 per cent of that in the USA.’ (Maddison, 1998) (Maddison & Wu, p. 1) Maddison also concluded that in these terms in 2008 US GDP was $9.5 trillion and China’s $8.9 trillion – i.e. on this measure China’s economy was 94 per cent the size of the US (Maddison, 2010).9

Subramanian reports that the new version of the Penn Tables, to be released in February 2011, will revise its estimate of China’s PPP up by 27 per cent (Subramanian, 2011).

Utilising such higher PPP estimates of the size of China’s GDP can give projections for when China’s GDP will overtake the US which are very short – as already noted that it has already occurred in the case of Subramanian and that it will occur in 2012 in the case of The Conference Board. It may be noted, however, that even the IMF, utilising its own lower estimates, now projects that China’s GDP will overtake the US in PPP terms shortly after 2015 (International Monetary Fund, 2010).

Valuable as PPP methodology is, however, due to the high degree to which estimates based on PPPs depend on the calculated PPP exchange rates, and because actual transactions are carried out at market prices, primary emphasis here will be on calculations based on market exchange rates and PPPs are used only for comparison.

Combination of PPP and exchange rate studies

A series of studies which have sought to compare market exchange rate and PPP data for the relative size of the US and China’s economies are by Hawksworth and collaborators for PWC. (Hawksworth, 2006) (Hawksworth & Cookson, 2008) (Hawksworth, 2010) (Hawksworth & Tiwari, 2011)

These successive studies have progressively brought forward their estimate of the date at which China’s GDP will equal that of the US. In the 2008 study China was projected to overtake the US in PPP terms in 2025 (Hawksworth & Cookson, 2008, p. 2). In the most recent, 2011, study China: ‘is expected to overtake the US as the world’s largest economy (measured by GDP at PPPs) sometime before 2020.’ (Hawksworth & Tiwari, 2011, p. 8).

Even more striking is the degree to which the PWC studies have brought forward the date at which China is projected to overtake the US in terms of market exchange rates. In its 2006 study PWC projected that China’s GDP would still be six per cent smaller than the US at market exchange rates in 2050 (Hawksworth, 2006, p. 22). By the 2011 study China was projected to overtake the US at market exchange rates in 2032. (Hawksworth & Tiwari, 2011, p. 16)

Goldman Sachs

In similar fashion to PWC, Goldman Sachs, which made the earliest well known projection of when China’s GDP will exceed that of the US, has also progressively brought forward its date for this – these estimates have been made as part of Goldman Sachs BRIC studies. In 2003 Goldman Sachs predicted that China’s economy would be larger than the US by 2041 (Wilson & Purushothaman, 2003).10 Goldman Sachs however subsequently noted that China, in particular, was growing substantially faster than its earlier projections.11 Thus, for example, in December 2009 it analysed: ‘how the BRIC economies stand today compared with how we projected them to be back in 2003… All four economies have attained levels of USD GDP that we had not originally expected until later – with China, of course, the main standout. We now assume a much stronger GDP performance for China by 2050 than we originally estimated. (O’Neill & Stupnytska, 2009, p. 5) More succinctly ‘China tops the list of countries whose growth performance has surpassed our expectations.’ (O’Neill & Stupnytska, 2009, p. 4) The date for China’s economy exceeding the US was brought forward to 2027 (O’Neill, 2009).12

Goldman Sachs 2003 prediction was based on projecting that China’s GDP in nominal dollar terms would increase at 8.1 percent a year. In fact in 2000-2010, the most recent 10 year period for which data is available , China’s annual nominal dollar GDP growth was 17.2 percent.13

Goldman Sachs has not revised its own BRIC forecasts since 2008. Even then, as seen, its assumptions had tended to underestimate China’s growth rate – and since 2008 the US economy has lost momentum, due to the international financial crisis, while China has not. When Goldman Sachs next revise their forecast as to the date when China’s economy will be as large as the US they will almost certainly bring it forward – as they have done in major previous revisions.

Different variables

For calculations made at market exchange rates, the date at which China’s GDP will equal the US primarily rests on the assumptions made regarding the rate of growth in constant prices of the US and China’s economies, their respective inflation rates, and the exchange rate of the RMB relative to the dollar. It is, therefore, possible to make a range of combinations of assumptions regarding these variables – The Economist has even produced a ready reckoner with which to do so! (The Economist, 2010)) The issue is evidently what range of values it is reasonable to insert and what is the sensitivity of the result for such different variables?

The Economist’s central projection was that annually China’s economy grows at 7.75 per cent, its inflation is 4.0 per cent and the yuan revalues by 3.0 per cent a year against the dollar, while the US grows at 2.5 per cent and its inflation is 1.5 per cent. This combination yields the result that China’s GDP overtakes the US at market exchange rates in 2019.

Interestingly, as also found when doing research at Antai College, the combination of such variables yield results which are not highly sensitive to any precise entry of figures which lie within historically reasonable ranges. For example, leaving all other parameters the same as in The Economist’s variant above, and increasing China’s growth rate to its average since 1978 of 9.9 per cent, only brings forward the date in which China’s GDP overtakes the US to 2018. The same result is obtained by using the highly favourable assumption to China of 9.9 per cent annual growth and utilising the 10 year annual growth rate of US GDP of 1.7 per cent (Ross, 2011a). Even taking the wildly favourable assumptions for China, all other things remaining equal, of 9.9 per cent GDP growth, 5.0 per cent yuan appreciation, and US growth at 1.7 per cent, only brings the date forward to 2017. Similarly taking a highly favourable conclusion for the US that its growth rate over the next decade accelerates to its historical 3.4 per cent, which is above its average growth rate for last 20 years, and assuming China’s growth decelerates to 7.75 per cent, and taking the Economist‘s assumptions as above for inflation and exchange rates, only pushes out the date China’s GDP overtakes the US to 2020.

These variants therefore confirm the author’s own studies that, provided any historically reasonable range of variables is used, the results target a relatively narrow range of 2017-2021, centred on approximately 2019.

A sense check

There is, however, another way to carry out such estimates. This is to do a ‘quick and dirty’ sense check calculation of the relative rates of growth of the US and China’s nominal dollar GDPs. As robust projections normally rely on having a small number of assumptions, and this is preferable to excessive numbers of variables, such estimates are of interest.

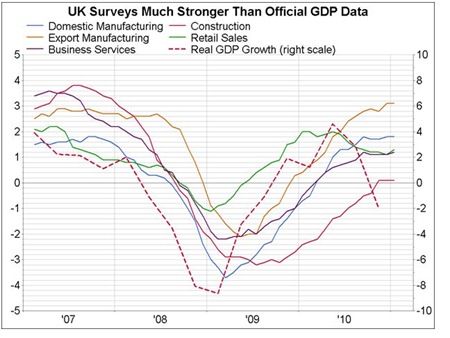

Such ‘quick and dirty’ methods consists of simply analysing the trends in nominal GDP, at official exchange rates, of China and the US without attempting to decompose these into movements in real GDP growth, inflation and exchange rate movements – such overall trends in nominal GDP in dollars may be taken as ‘summarising’ the GDP growth, inflation and exchange rate movements.14 Making such an analysis strikingly reveals clear long term trends illustrated in Figure 1 and Table 1. These show:

- the rate of growth of US nominal GDP is decelerating with time – i.e. the more recent the period of time the lower the growth rate of nominal US GDP.

- China’s GDP growth rate in current dollar terms is accelerating – i.e. more recent periods show higher growth rates than older ones.

Continuation of such trends, of course, implies that linear projection of past growth rates, i.e. those not taking into account the deceleration of US nominal GDP growth and the acceleration of China’s, will tend to overstate the period until China’s GDP exceeds the US.

Figure 1

Table 1

Taking precise figures, if the overall period from the beginning of China’s economic reforms, in 1978, to the latest available data for 2010 is considered then the annual rate of increase of US nominal GDP is 6.0 per cent. However if the most recent two decade period 1990-2010 is taken annual US nominal GDP growth is 4.8 per cent. If the most recent 10 year period 2000-2010 is taken then annual US GDP growth is 4.1 per cent. If the most recent 5 year period is taken, 2004 to 2009, then the annual average increase in US nominal dollar GDP is 3.1 per cent.

The deceleration of US GDP growth in terms of current prices and current exchange rates is therefore evident. An element in this, as analysed elsewhere, is not only the deceleration of US inflation rates in the recent period but also the gradual slowing of the US economy in real constant price terms (Ross, 2011c).

China shows the reverse trend. If the overall period since the start of economic reform, i.e. 1978-2010, is taken then China’s annual nominal dollar GDP growth is 12.2 per cent.15 If the most recent 20 year period 1990-2010 is taken then annual nominal GDP growth is 15.0 per cent. If the most recent 10 year period 2000-2010 is taken then annual nominal dollar GDP growth is 17.2 per cent (calculated from World Bank, 2010). If the most recent 5 year period is taken, 2005 to 2010, then the annual average increase in nominal dollar GDP is 21.1 per cent. The rate of growth of China’s GDP in nominal dollar terms has therefore clearly shown an accelerating trend.

To take a central illustrative case of such trends, if a linear projection of the last 10 year period is taken then the answer as to when China’s GDP will overtake the US at market exchange rates is 2019. As, however, the trend is for acceleration of China’s growth rate in nominal dollar terms, and for deceleration of the US, then 2019 might be taken, using this method, as an indication of an outer bound of when China’s GDP overtakes the US.

Sensitivity of the results

Fortunately, and interestingly, it again turns out that provided projections made using such estimates are within the realm of reasonable results based on past performance, then results are not extremely sensitive to precise figures used.

As shown in Table 2, if the ultra-favourable assumption for China were made that its annual growth rate in nominal dollar GDP remained that of the last five years, i.e. 21.1 per cent, and the growth rate of the US also remained at that of the last five years, i.e. 3.1 per cent, then China’s GDP still does not overtake the US until 2016 – however this five year period is too short to be used for serious projections, particularly as it includes the impact of the international financial crisis, and is therefore not taken here as part of the central results but treated as an outlier used for illustrative purposes. If China’s and the US’s 10 year average growth of nominal dollar GDP are taken, i.e. respectively 17.2% and 4.1%, then China’s GDP exceeds the US in 2019. If a 20 year average growth of nominal dollar GDP increase for China and the US is taken, respectively 15.0% and 4.8%, then China’s GDP exceeds the US in 2020.

In short, unless a drastic change in the relative behaviour of China and the US’s GDP is assumed, of a type not experienced in the last 20 years, then China’s GDP will exceed that of the US sometime in the period 2016-2021 with 2019 a central point of such a range. A graph for the latter projection, using 10 year averages, is shown in Figure 2.

A ‘quick and dirty’ sense check therefore coincides with analysis based on the wider series of values for real constant price growth rates, inflation rates and exchange rates.

Table 2

Figure 2

The qualitative features

What conclusions may be drawn from the above data?

It is not particularly valuable to attempt to refine the figures further to arrive at a more precise date – too many elements, with too high a degree of uncertainty, exist to try to determine whether China’s GDP will exceed that of the US in, for example, 2018 or 2020. What is significant, however, is that on any input of the range of actual comparative performance during the last twenty years China’s economy, in current exchange rate terms, will exceed the US at some point during the period 2017-2021. Furthermore such a date range is not greatly sensitive to changes in reasonable, in light of past performance, inputs.

Such a finding has a precise economic meaning. It means that some fundamental change must take place in existing trends within approximately a ten year time frame for China’s GDP at market prices not to overtake the US in the period 2017-2021.

If, as pointed out above, PPP calculations lead to excessively early projections for when China’s GDP will exceed the US, it is equally the case that projections that China’s GDP will not overtake the US at market exchange rates within the range 2017-2021 have to rely on asserting that an absolutely fundamental change will take place during the next decade. The ‘status quo’ scenario is that China’s GDP at market exchange rates will exceed the US in this period.

While, of course, a sharp change in relative inflation or exchange rates could produce a significant change in the above trends most frequently those who assert that China’s GDP will not overtake the US during the coming decade postulate a major change in relative US and China constant price growth rates. For these to prevent China’s GDP overtaking the US at market exchange rates during the next ten years it must be postulated either that a fundamental acceleration of the US economy will occur or, as few analysts predict such a development, more usually it must be asserted that for some reason a severe slowing of China’s economy during the next decade will occur.16

It is perhaps due to a difficulty in accepting the reality of China overtaking the US as the world’s largest economy that there exists a large ‘catastrophist/drastic slowdown’ literature on China.17 Detailed examination of these various perspectives is beyond the scope of this paper. For present purposes it is sufficient to note that short of such a drastic slowdown in the near future, that is on the basis of continuation of the trends that have prevailed over the last decades, China’s GDP at market exchange rates will overtake the US approximately in 2017-2021.

For purposes of qualitative analysis, the simplest way to cut through the Gordian knot of detailed calculations is that China’s GDP ‘in approximately ten years time will be approximately the same size as the GDP of the US’. This will, of course, constitute a new period in world economic history.18

Conclusions

The following fundamental conclusions follow from the above data and review:

- The majority of international analysis of China’s underestimated its growth and considered as likely to produce more favourable results ‘shock therapy’ pursued in the former USSR. It is no longer possible to sustain such analysis in the light of the test of economic development over almost three decades. China’s economic approach has been overwhelmingly more successful than shock therapy.

- Even studies which have emphasised the shifting balance of economic weight towards emerging markets, such as those of Goldman Sachs and PWC, have nevertheless systematically underprojected China’s growth. They have therefore successively revised upwards their estimates for the development of China’s GDP.

- The majority of such projections now estimate that China’s GDP in PPP terms will exceed that of the US in the period prior to 2020.

- Such projections continue to lag behind trends as they do not grasp that China’s GDP at market prices will also equal the US in the period to 2017-2021.

* * *

This article originally appeared on the blog Key Trends in Globalisation.

Notes

1. The world ‘national’ is necessary to avoid ambiguity regarding the European Union (EU), which taken as a whole is larger than the US. However the EU is not a state integrated economy and its role in determining world economic policy is therefore significantly less than the US.

2. These show a gradual but clear long term slowing trend of annual US GDP growth, at constant prices, from its level of 3.4% over the last century, to a current 2.6% 20 year moving average and a 1.7% 10 year moving average (Ross, 2011a) (Ross, 2011d).

3. For a typical survey see (Aslund, 1995).

4. The term BRIC was first introduced in the paper Building Better Global BRICs (O’Neill, 2001) (O’Neill, Wilson, Purushothaman, & Stupnytska, 2005)

5. As Hawksworth and Tiwari note: ‘GDP at PPPs is a better indicator of average living standards or volumes of outputs or inputs, because it corrects for price differences across countries at different levels of development. However, GDP at MERs [Market Exchange Rates] is a better short term measure of the relative size of the economies from a business perspective, at least in the short term.’ (Hawksworth & Tiwari, 2011, p. 6).

6. The unweighted average daily dollar RMB exchange rate for 2010 is 6.7709 and on this basis China’s 2010 GDP was $5878.1. These figures are used for all calculations below.

7. The precise figure for US in 2010 was $14 660.2bn.

8. For a survey of methodologies and difficulties see (Deaton & Heston, 2008). Maddison stressed: ‘Exchange rates are a misleading indicator of comparative real values.’ (Maddison, 1998, p. 154)

9. For further details of this method of calculation see (Deaton & Heston, 2008).

10. It may seem surprising, in light of subsequent developments, that in 2001 Goldman Sachs was only predicting: ‘If the 2001/2002 outlook were to be repeated for the next 10 years, then by 2011 China will actually be as big as Germany on a current PPP basis.’ (O’Neill, 2001) By 2011 China’s GDP is in fact larger than every country in the world except the US.

11. In 2009 the Goldman Sachs studies concluded: ‘Since we first estimated the long-term growth potential of the BRIC… economies up to 2050, we have updated the original estimates four times… the size of all of the BRIC economies at the end of 2008 in current USD is much bigger than we originally estimated in 2003. In fact, each of them has grown to a size we didn’t expect to see until much later… China, which is about to overtake Japan (about six years earlier than we first thought) may become as big as the US within 20 years.’ (O’Neill & Stupnytska, 2009, p. 21)

12. Jim O’Neill noted in March 2009: ‘While I predicted a few years back that the BRIC economies would together be larger in dollar terms than the G7 by 2035, I now believe that this shift could happen much faster – by 2027.” (O’Neill, 2009b)

13. Making this point is not intended as a criticism of Goldman Sachs’ BRIC view. On the contrary Jim O’Neill’s was a brilliant case of how to get it right regarding fundamental trends. O’Neill has consistently made qualitative the right calls regarding China – for example in correctly estimating that China’s stimulus package to deal with the international financial crisis would be successful. As he noted in 2009, against critics who believed China would not be able to maintain a rapid growth rate confronted with a crisis in the US and other developed economies: ‘Who said decoupling was dead? The decoupling idea is that, because the BRICs rely increasingly on domestic demand, they can continue to boom even if their most important export market, the United States, slows dramatically… While many now say decoupling was a crazy idea… evidence suggests very strongly that it was working in a big way… At the heart of this shift in consumer power is China. Its total economy already equals that of the other three BRICs put together, and what happens to China is critical for the BRICs, and the world. With the authorities announcing plans to introduce medical insurance to 90 per cent of the rural community by 2011, a huge infrastructure-spending program and a massive easing of monetary and financial conditions, the only debate in my mind is exactly when China will restore its growth rate back above 8 percent.’ (O’Neill, 2009b)

Goldman Sachs, in short, placed itself on the right playing field. It was those who criticised Goldman Sachs views on BRIC who were shown to be quite wrong. If, in 2001, Goldman Sachs had projected China’s economy would be larger than the US by 2027 few would have taken such views seriously. The above points are made therefore simply made to clarify that far from Goldman Sachs BRIC views being too optimistic regarding the potential growth of China’s economy they underestimated its growth.

14. Evidently current price GDP calculations are of no use if real growth rates are being examined, but in this issue what is being examined is the relative size of the US and China’s economies for which current prices growth rates are valid.

15. These calculations assume China’s GDP at current exchange rates in 2010 to be $5 878.1 – the eventual official figure will produce an entirely marginal difference to the calculation.

16. This issue is different to the one of whether there is a tendency for economies to decelerate as they become more developed and therefore what will be China’s growth rate over a period say to 2030-2050. For China’s GDP not to overtake the US due to it decelerating such a slow down must, for reasons indicated above, take place during the next decade.

17.Dale Jorgenson, one of the world’s leading experts on productivity and growth, was noted by Reuters as stating that the, ‘United States will need to come to terms with the fact that its prevalence in the world is fated to come to an end,… This will be difficult for many Americans to swallow and the United States should brace for social unrest amid blame over who was responsible for squandering global primacy.’ Reuter’s also noted stronger predictions regarding China’s growth by some US economists: ‘MIT’s Simon Johnson put it more bluntly, saying the damage from the financial crisis and its aftermath have dealt U.S. prominence a permanent blow.”The age of American predominance is over,” he told a panel. “The (Chinese) Yuan will be the world’s reserve currency within two decades.”‘ (Felsenthal, 2011)

Authors of perspectives of drastic slow down of China’s economy continue for some reason to receive regular publicity for their views in sections of the media despite the fact that similar predictions have been falsified over several decades.A few examples may therefore be given:

– Gordon Chang’s The Coming Collapse of China asserted in 2002: ‘A half-decade ago the leaders of the People’s Republic had real choices. Today they do not. They have no exit. They have run out of time.’ (Chang, 2002, p. xxiii) This prediction ‘they have run out of time’ was followed by eight years of extremely rapid Chinese GDP growth.

– Michael Pettis projects a deceleration of China’s growth to 3-5 per cent over the rest of the decade – due to difficulties in developing consumption and other issues (Pettis, 2010).

– James Mackintosh, investment editor of the Financial Times, asserts: ‘There are plenty of potential triggers for a slowdown [in China]. Policy measures to control runaway food price inflation could work too well. The housing bubble in large cities could burst, rather than deflating slowly, and could hit over-indebted local authorities. Finally, the state-controlled banks may need another big injection of cash to make up for their wild lending over the past two years, taking resources away from the rest of the economy.’ (Mackintosh, 2011)

– James Rickards, former general counsel of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management, and now the senior managing director for market intelligence at consulting firm Omnis, claims China is in the midst of ‘the greatest bubble in history’ stating that the Chinese central bank’s balance sheet resembles that of a hedge fund buying dollars and short-selling the yuan. (The Economic Times, 2010)

18. In terms used by Hawksworth, such a development would mean ‘ending over a century of US economic hegemony’ (Hawksworth, 2010).

Bibliography

Adam, S. (2010, November 15). China May Surpass U.S. by 2020 in `Super Cycle,’ Standard Chartered Says. Retrieved January 21, 2011, from Bloomberg: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-11-15/china-may-surpass-u-s-by-2020-in-super-cycle-standard-chartered-says.html

Aslund, A. (1995). How Russia Became a Market Economy. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Bureau of Economic Research. (2010, December 22). NIPA Table 1.5.5. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from Bureau of Economic Analysis: http://www.bea.gov/national/nipaweb/TableView.asp?SelectedTable=35&Freq=Qtr&FirstYear=2008&LastYear=2010

Central Intelligence Agency. (2011, January 12). The World Factbook. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from Central Intelligence Agency: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ch.html

Chang, G. C. (2002). The Coming Collapse of China. London: Arrow Books.

China Daily. (2010, August 17). When will China economy surpass US? Retrieved January 19, 2011, from China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2010-08/17/content_11166379.htm

Deaton, A., & Heston, A. (2008). Understanding PPPs and PPP-based national accounts. Cambridge Massachusetts: NBER.

Dunkley, E. (2011, January 13). China to overtake US by 2018 – PwC. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from Investment Week: http://www.investmentweek.co.uk/investment-week/news/1936788/china-overtake-2018-pwc

Felsenthal, M. (2011, January 9). Economists foretell of U.S. decline and China’s ascension. Retrieved January 14, 2011, from Reuters: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/01/09/uk-usa-economy-gloom-idUKTRE7082AW20110109?pageNumber=1

Hawksworth, J. (2010, January). Convergence, Catch-Up and Overtaking: How the balance of world economic power is shifting. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from PWC: http://www.ukmediacentre.pwc.com/imagelibrary/downloadMedia.ashx?MediaDetailsID=1626

Hawksworth, J. (2006, March). The World in 2050 – How Big Will the Major Emerging Market Economies Get and How Can the OECD Compete? Retrieved February 8, 2011, from PWC: http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/pdf/world2050emergingeconomies.pdf

Hawksworth, J., & Cookson, G. (2008, March). The World in 2050 – Beyond the BRICs: a Broader Look at Emerging Market Growth Prospects. Retrieved February 8, 2011, from PWC: http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/pdf/world_2050_brics.pdf

Hawksworth, J., & Tiwari, A. (2011, January). The World in 2050 – The Accelerating Shift of Global Economic Power: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved February 8, 2011, from PWC: http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/world-2050/pdf/world-in-2050-jan-2011.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2010, October). World Economic Outlook October 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from International Monetary Fund: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/02/weodata/index.aspx

Mackintosh, J. (2011, January 2011). History shows China slowdown due. Retrieved January 26, 2011, from Financial Times: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/d64200b8-26c6-11e0-80d7-00144feab49a.html?ftcamp=rss#axzz1BfEyxaV7

Maddison, A. (1998). Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run. Paris: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Maddison, A. (2010). Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD . Retrieved January 23, 2011, from Angus Maddison (1926-2010): http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm

Maddison, A., & Wu, H. X. (n.d.). China’s Economic Performance: How Fast Has GDP Grown; How Big is it Compared with the USA. Retrieved January 15, 2011, from http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2011, January 20). National Economy Showed Good Momentum of Development in 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from National Bureau of Statistics of China: http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20110120_402699463.htm

O’Neill, J. (2001, November 30). Building Better Global Economic BRICs Global Economics Paper No: 66. Retrieved January 24, 2011, from Goldman Sachs: http://www2.goldmansachs.com/ideas/brics/building-better.html

O’Neill, J. (2009, April 23). China show the world how to get through a crisis. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from Financial Times: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/dd9b5a1e-2f9f-11de-a8f6-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1BfEyxaV7

O’Neill, J. (2009b, March 21). The New Shopping Superpower. Retrieved January 27, 2011, from Newsweek: http://www.newsweek.com/2009/03/20/the-new-shopping-superpower.html

O’Neill, J., & Stupnytska, A. (2009, December 4). The Long Term Outlook for the BRICs and N-11 Post Crisis Global Economics Paper No: 192. Retrieved January 27, 2011, from Goldman Sachs: www2.goldmansachs.com/ideas/brics/long-term-outlook-doc.pdf

O’Neill, J., Wilson, D., Purushothaman, R., & Stupnytska, A. (2005, December 1). How Solid are the BRICs Global Economics Paper No: 134. Retrieved January 25, 2011, from Goldman Sachs: http://www.goldman-sachs.com/ideas/brics/how-solid.html

Pettis, M. (2010, December 19). Chinese growth in 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2011, from China Financial Markets: http://mpettis.com/2010/12/chinese-growth-in-2011/

Rachman, G. (2011, January 16). When will China become the world’s largest economy? Retrieved January 19, 2011, from Financial Times: http://blogs.ft.com/rachmanblog/2011/01/when-will-china-become-the-worlds-largest-economy/

Ray, T. (2010, November 10). Conference Board: China’s GDP To Surpass U.S.? Retrieved January 19, 2011, from Barron’s: http://blogs.barrons.com/stockstowatchtoday/2010/11/10/conference-board-china-gdp-could-surpass-us-in-2012/

Ross, J. (2011c, January 17). Average economist predictions for US GDP would mean only 0.9% annual average growth over business cycle to end 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2011/01/average-projections.html

Ross, J. (2011b, January 13). Long-term and short-term cyclical prospects for US growth. Retrieved January 28, 2011, from http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2011/01/prospects-for-us-growth.html

Ross, J. (2011a, January 9). The long term slowing of the US economy – and its implications. Retrieved January 26, 2011, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2011/01/slowing_of_the_us_economy.html

Ross, J. (2011d, February 1). US 4th quarter 2010 GDP shows cyclical upturn and continued long term economic deceleration. Retrieved February 1, 2011, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2011/02/us-4th-quarter-2010-gdp.html

Ross, J. (1992, April 3). Why the economic reform succeeded in China and will fail in Russia and Eastern Europe. Retrieved February 10, 2011, from Key Trends in Globalisation: http://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/1992/04/why-the-economic-reform-succeded-in-china-and-will-fail-in-russia-and-eastern-europe.html

Subramanian, A. (2011, January 13). Is China Already Number One? New GDP Estimates. Retrieved January 19, 2011, from Peterson Institute for International Economics: http://www.piie.com/realtime/?p=1935

The Conference Board. (2011, January). The Conference Board Total Economy Database. Retrieved January 22, 2011, from The Conference Board: http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/

The Economic Times. (2010, March 18). ‘China faces the ‘greatest bubble’ in history’. Retrieved January 26, 2011, from The Economic Times: http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international-business/China-faces-the-greatest-bubble-in-history/articleshow/5695593.cms

The Economist. (2010, December 16). Dating game: When will China overtake America? Retrieved January 19, 2011, from The Economist: http://www.economist.com/research/articlesBySubject/displayStory.cfm?story_id=17733177&subjectID=348918&fsrc=nwl

Ward, K. (2011, January). The World in 2050 – Quantifying the Shift in the Global Economy. Retrieved February 8, 2011, from HSBC Global Research: http://www.research.hsbc.com/midas/Res/RDV?ao=20&key=ej73gSSJVj&n=282364.PDF

Wilson, D., & Purushothaman, R. (2003, October 1). Dreaming with BRICs: The Path to 2050 Global Economics Paper No: 99. Retrieved January 27, 2011, from Goldman Sachs: http://www2.goldmansachs.com/ideas/brics/brics-dream.html

World Bank. (2007, December 17). 2005 International Comparison Program Preliminary Results. Retrieved January 23, 2011, from World Bank: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ICPINT/Resources/ICPreportprelim.pdf

World Bank. (2010). World Development Indicators. Retrieved February 10, 2011, from World Bank: http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/home.do?Step=12&id=4&CNO=2

John Rosshttps://www.blogger.com/profile/08908982031768337864noreply@blogger.com0

Recent Comments