Did New Labour spend too much?By Michael Burke

It is not sufficient for big business to have secured an election victory and an overall Parliamentary majority for the Tory Party. It is also necessary to intervene in the Labour Party to ensure that its leadership also conforms to big business interests too. This has currently taken the form of candidates in the leadership contest being asked to declare that Labour ‘spent too much’ in the run-up into the Great Recession. Answering Yes to this question is effectively a loyalty oath to big business interests, a renunciation even of the social democratic vestige of economic policy under New Labour.

The question is economically illiterate. It is taken as axiomatic that if there was a deficit that spending must have been too high. But all deficits are composed of two items; spending and income. In the case of government that income arises mainly in the form of taxes. It does not follow from the existence of a deficit that the culprit must be spending.

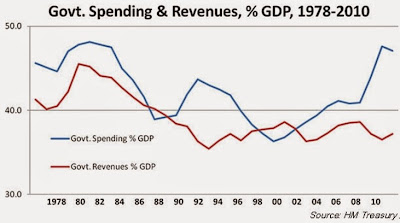

The reality is that measured as a proportion of GDP New Labour spent less on average than Margaret Thatcher. This is shown in Fig. 1 below. On average New Labour’s spending amounted to 41.5% of GDP. By comparison, under Thatcher government spending was 44.2%. In relation to the deficit, the taxation levels were also very different. Under New Labour taxation revenues were on average 37.5% of GDP. Under Thatcher taxation revenues amounted to 42.0% of GDP.

The argument that Labour spent too much has no factual basis whatsoever. The loyalty test of renouncing the ‘overspend’ is based on a complete fiction. In fact, because it was in thrall to neoliberal economics, it is clear that New Labour taxed too little.

Under New Labour the main rate of corporation tax on profits was cut from 34% to 28%. ‘Taper relief’ on capital gains was introduced which cut the tax rate on capital gains (CGT) from 40% to 24%. This system was later scrapped and the rate cut to 18% by Alistair Darling. Owners of assets therefore paid a far lower tax rate than the tax on workers’ income. A system was also introduced where, almost uniquely in advanced economies, companies could set off both past losses against corporation tax, and carry back losses to reduced their tax bill too.

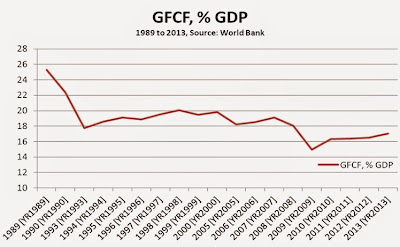

None of this led to an increase in productive investment, which was the supposed reason for these huge giveaways to capital. Instead there was a very substantial increase in speculative investment, which did contribute to the crash. On the contrary, investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, GFCF) continued its long-term decline, as shown in Fig.2 below.

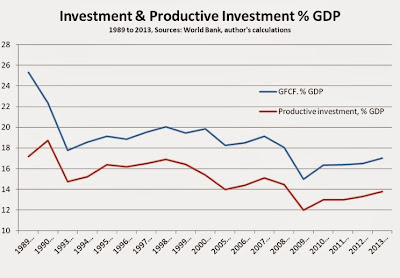

The effect of boosting speculative investment is indicated by the growth of housing as a component of the pre-crash British economic expansion. Fig. 3 below shows the level of GFCF and the level of productive investment, that is GFCF omitting housing. This clearly shows that the decline in productive investment was uninterrupted throughout the period of New Labour as well as before and since under the Tories. In this entire period economic policy was neoliberal dominance which meant there was an explicit aim of reducing taxes on business in order to increase investment. The policy was a complete failure.

The trend towards lower productive investment by the private sector and increased speculative activity was also fostered by the government’s cuts to the level of public sector investment. The data and OBR projections are shown in Fig.4 below. As government is the biggest single purchaser of goods and services in the economy, cutting government investment encourages the private sector to cut its own investment.

It is one of the central myths of neoliberal economics that government investment ‘crowds out’ private sector investment. The opposite was the case; a cut in government investment accompanied declining productive investment by the private sector. By contrast, rhe temporary rise in public sector investment in 2008 and 2009 helped to lift the economy out of recession and was rapidly ended by the last Coalition government.

New Labour did not spend too much. It taxed and spent too little, less than Thatcher. Worse, the cuts in taxes for the business sector and the owners of assets did not lead to increased investment. Investment fell and was itself exacerbated by the decline in public sector investment.

Defence of these simple facts has been made an acid test. They are actually the vestiges of social democratic economic policy at the level of the Labour leadership. If it is accepted that Labour ‘spent too much’, big business interests will have rewritten history in its own interests and fundamentally undermined the character of the Labour Party.

Recent Comments