By Michael Burke

The widespread claims that the latest Budget is not an austerity Budget, even that it is borrowing Labour’s clothes, are both factually and logically false.

The purpose of this article is first to set out the factual position in relation to government spending, and then to offer a framework in judging the over stance of fiscal policy. From these two key points it can be shown that this is another, quite vicious austerity Budget and that to argue otherwise both disarms and discredits the labour movement in the face of this attack.

Facing facts

The government have conducted a major sleight of hand when it comes to the presentation of the policy it has adopted in the latest Budget and Spending Review. This con trick is highlighted in a key Treasury table below.

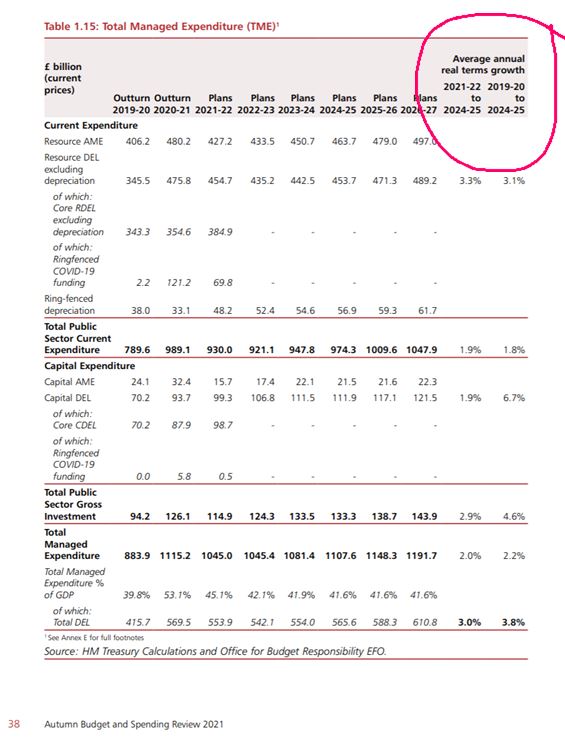

Table 1. Total Managed Expenditure (TME)

This TME table is one of the key pieces of information in any Treasury Budget document as it gives the summary data for many of the key totals for government spending. For anyone analysing the Budget, it is one of the first things they will examine.

But here the presentation of the data is misleading, probably deliberately so. In the top right-hand corner of the table highlighted there are two columns, showing the growth in the expenditure variables in real terms (adjusted for inflation). The first shows the growth in real terms in the Fiscal Year 2021-22 to the FY2024-25. The second of these columns shows the same end date FY2024-25, but the start date is 2019-20.

What is missing is a column with the start date FY2020-21, which is the most recent Fiscal Year, that ended at the beginning of April 2021. As a result, there is no measure of future years in comparison to the one that has most recently ended, which is the normal yardstick for assessing any change in policy.

There is a good reason for this. The start date of this most recent year would show a very different outcome. Instead of rising in real terms there would be sharp falls in real terms. In fact, using the FY that has just ended of 2020-21, there are falls even in nominal terms (before inflation) which are shown in the preceding columns.

To illustrate this, Total Public Sector Current Expenditure was £989.1bn in FY2020-21 and is projected to fall to £974.3bn in 2024-25. The same is true of Total Managed Expenditure (which includes gross investment as well as day-to-day spending, but does not include depreciation). This falls over the same period from £1115.2bn in FY 2020-21 to £1107.6bn in 2024-25.

Remember too that the totals in these columns are in nominal terms, before inflation is taken into account. Using inflation forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) the present author calculates that prices will rise by a cumulative 12.5% over the period. So, in real terms (adjusted for inflation) Total Public Sector Current Expenditure will be £852.5bn in 2024-25, while Total Managed Expenditure will be £969.2bn. These would represent falls of 13.8% and 26.7% respectively in real terms.

To be clear, these are the gross totals where each of the government spending departments together comprises those totals. This is a planned and very deep cut to government spending. It amounts to a vicious deepening of austerity.

The sleight of hand is made possible by the government including the huge increase in spending, an extra £200bn in 2020-21 that was forced on it by the pandemic, while it is slashing that extra spending in future years.

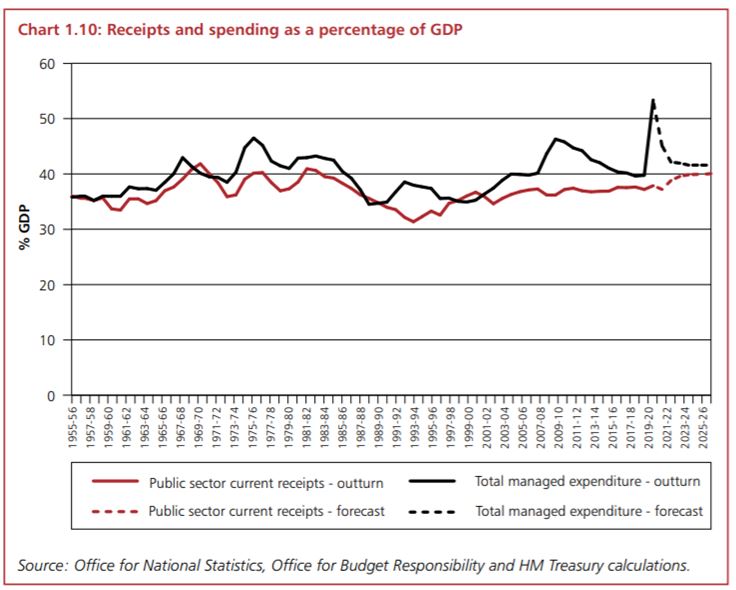

The overall picture becomes even clearer in the Chart below, which shows total government receipts and spending in relation to GDP.

Chart 1. Government Spending and Receipts as a percentage of GDP

From this it is clear that, measured in relation to GDP growth, there was a spike in government spending in the first year of the pandemic. This was caused by its own complete failure in responding to the outbreak of the virus, and the human and economic damage that resulted. This country has had far more days of lockdown that other countries which successfully suppressed the virus.

However, the government now proposes (shown in the black dotted line) to reverse almost the entirety of that increased spending almost immediately. This is something like a 10% to 11% decline in public spending as a proportion of GDP.

It is worth noting that the government’s timetable for that scale of reduction is literally a couple of years. There was an equivalent decline in government spending achieved by Margaret Thatcher over the course of 10 years, but that was at a time of relatively strong growth due to the inrush of North Sea oil. No such period of higher growth is anticipated for the period ahead, which would require the cuts to government spending to be applied even more ferociously.

Government apologists claim that spending is returning to normal as the economy returns to normal. Of course, the pandemic is far from over, so the assertion is highly doubtful. But as even the OBR suggests, the combination of Brexit and the pandemic has left permanent ‘scarring’ on the economy, so it is not going to return to ‘normal’. Under these circumstances, there is no justification for ripping the bandages off the scarred patient and discharging her from hospital.

Total government spending is being slashed in real terms and as a proportion of GDP. The notion that this constitutes an end to austerity is simply without any factual foundation.

Fiscal policy matters

The overall stance of fiscal policy cannot simply be gauged by the amount of spending and whether it is increasing.

It has already been shown that in fact, government spending is falling in real terms, as a proportion of GDP and in nominal terms. However, even if that were reversed and spending was rising, that would not be the key determinant of fiscal policy. Government priorities for tax and spend affect different classes of society unevenly. What matters, is who receives the spending, who is being taxed.

Suppose a bad teacher has a packet containing 12 biscuits and chooses two favourites among the class who are given 3 biscuits each. The rest of a class of 30 are told to fight among themselves for the remaining 6 biscuits. When the rest of the class complains that this is unfair, the teacher brings in a packet of 15 biscuits. But now the two favourites receive 5 biscuits each, leaving the rest of the class fighting over 5 biscuits. Even though resources are increased, their distribution has become more unequal, not less.

Austerity is about the distribution of resources, not about the level of government spending. Indeed, extreme right-wingers like John Redwood like to claim there has been no austerity because government spending has risen. Of course, he is wrong. There has been fierce austerity despite a rise in government spending.

As Chart 1 above shows, an upward trend in government spending has been in place since 1990. But that did not stop Osborne and Cameron, in one of their first major austerity measures from increasing VAT (overwhelmingly paid by those on average on lower incomes) while cutting Corporation Tax (paid on profits). As far as the Treasury was concerned this was ‘fiscally neutral’ as the rise in VAT yielded about £13bn and the tax cut was approximately worth the same. But the effect was to distribute incomes from mainly average and low earners to profit-making businesses.

In short, austerity cannot be determined by the level of government spending. As Diane Abbott and others have shown, the measures contained in the latest Budget were a vicious attack on low and average incomes earners and pensioners, with forecasts that real average earnings will fall, at the same time that bankers and other receive tax giveaways.

In this Budget there is both a reduction in spending, and a redistribution of spending from workers and the poor to bankers and higher paid. Austerity is the transfer of incomes and assets from poor to rich, from labour to capital. That is what this Budget implemented.

Calling things by their real name

It is possibly unfortunate for many readers that such a basic factual presentation and such elementary analysis has to be provided. But such is the level of confusion and outright deceit surrounding government policy, that basic truths are necessary.

The widespread assertion that austerity has ended is factually incorrect. High taxes are not progressive if they are paid by average earners to facilitate the privatisation of the NHS. The claim that a government cutting Universal Credit and state pensions, while cutting taxes on banks and presiding over a fall in real wages is ‘carrying out Labour policies’ insults the intelligence.

The repetition of these falsehoods discredits the labour movement and in particular all those who fought successfully for an ‘investment, not cuts’ approach that was adopted under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. Crucially, falling for this Tory con trick disarms the labour movement in arguing against the austerity measures and in mounting any defence against them.

Recent Comments