.912ZWhat level of investment should Corbyn & McDonnell aim for?By Michael Burke

The policies outlined by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell have the capacity to transform the economic debate in Britain. More importantly, if the ideas outlined for an investment-led recovery are implemented then they could alter the trajectory of the British economy, from stagnation and rising inequality towards sustainable growth and a general rise in living standards.

Therefore it is important to examine thoroughly what is the scale of the investment needed, which areas will be prioritised, what will be the overall effects on the economy, how it will be funded, and a number of other questions. Here, only an outline of the first question is addressed, what is the scale of the investment needed?

Identifying the problem

The population as a whole is primarily concerned with its own well-being, on matters such as wages, health care, good schools, good quality public services and (for themselves at least) some reassurance that social security will provide sufficient support if they cannot work. In general these fall under the economic category of Consumption.

SEB has shown over a number of articles that Consumption cannot drive economic growth. Consumption follows Production. Increasing Consumption alone simply leads to increased debt, a claim on future production. This is precisely what has occurred in the British and other economies since the crisis. Consumption has outstripped production and households in particular have been obliged to either increase debt or run down their savings. It is not sustainable. In order to increase production over the medium-term it is necessary to increase the means of production through Investment.

Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell have said on a number of occasions that they will borrow to invest (audio link & transcript) but will run a balanced budget on current government spending. This is correct. Only borrowing to achieve a positive return and economic growth. It is this Investment (and borrowing to fund it) that leads to higher living standards, including higher Consumption.

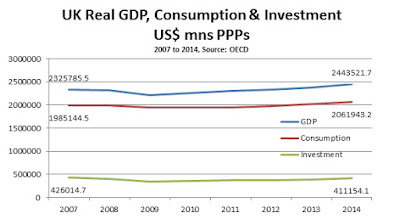

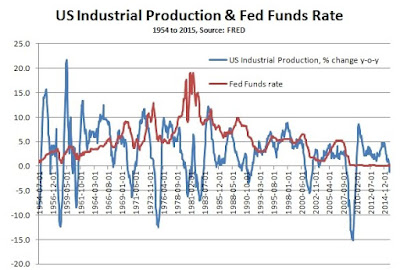

But it is precisely the level of investment which is currently the key drag on the British economy. In Fig.1 below the level of real GDP, Consumption and Investment from the beginning of 2000 onwards are shown. Trend lines for GDP and investment are also shown as these show the general trajectory rather the more short-term fluctuations.

One of the more ridiculous claims by the Tory Government is that its austerity policy is responsible for recovery. There has been no substantive recovery of the output lost in the slump. In most business cycles the sharpness of the recession is matched by the pace of the recovery. This business cycle is a rarity. None of the three key variables is anywhere near recovering its previous growth trend. As a result there is a risk that the loss of output will become permanent and the British economy will have shifted onto a long-term, lower growth trajectory.

The most important of these three variables in determining future growth is Investment. If GDP growth had continued on its previous trend it would now be 16% higher than its current level. But Investment has experienced the sharpest fall, and is currently 26% below its previous trend. In fact Investment is the only variable to remain below its pre-recession peak, although that may alter in the near future.

How much investment?

Because both the future level of GDP and Investment are unknown, it is impossible to say at this point what the precise level of additional Investment would be needed under a Corbyn-led Government. But it is possible to extrapolate from previous trends in order to demonstrate the approximate rate of Investment needed.

This can be done by replicating the trend rate of growth from 1st quarter of 2000 over 8 years to the pre-recession peak in the 1st quarter of 2008. If that growth trend was repeated over the following 8 years, by the 1st quarter of 2016 real GDP (annual) would be £2,090 billion. From the previous peak Investment would be £390 billion.

Investment is currently way below this level, around £310 billion. In the early part of 2016 it would require an annual additional increase in Investment of £82 billion in precise terms, from £310bn to return to trend growth rates. This would be an increase equivalent to 4% of GDP to 18.75% of GDP.

As the private sector has been unable or unwilling to produce an investment-led recovery, the public sector will be obliged to lead this increase in investment equivalent to 4% of GDP. This is in addition to the current miserably low rate of net public sector of 1.5% of GDP, bringing the total level of net public investment (after depreciation) up to 5.5% of GDP.

It is reasonable to assume that the private sector itself would then increase its own rate of investment to some extent, as the anticipated level of new profits would rise and based on past experience. But as this cannot relied on as the overall economic conditions at the outset of a future Labour Government are unknown, so this assumption cannot form a central part of the overall projection.

Competitiveness

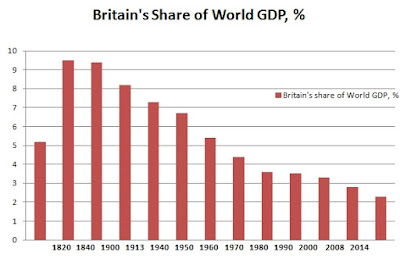

The issue of how much additional investment is not exhausted by reference to previous trends, particularly since the British economy has had a lower rate of investment than comparable economies over the very long-term. Simply returning to 2000 to 2008 rates of investment is a minimum requirement in order to prevent permanently embedding the effects of the slump.

Fig.2 below shows a comparison of labour productivity per hour in the UK and the rest of the G7 group of economies. UK productivity is now over 20% below that of the rest of the G7, the highest productivity gap on record. Since 2000 every country in the G7 has made gains relative to UK productivity.

UK productivity has also fallen in the recovery, which is extremely rare. Usually, existing plant, factories and machinery that have fallen idle in the slump is brought back into production and productivity rises. Instead, labour inputs have risen as the UK economy has employed more people in longer hours in low value-added jobs, so output has not grown at the same pace.

Despite much discussion there is no ‘puzzle’ behind the very weak level of UK productivity. It is because the UK has a very weak relative rate of investment. As the UK economy has a persistently lower level of fixed investment, so the relative decline in productivity is unavoidable.

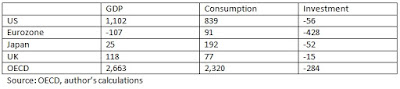

Productivity (labour output per hour) will increase in proportion to the increase in quantity and quality of machinery and other fixed capital used in output (as well as the skills level of the workforce). As Fig.3 below shows, throughout the entire period from 2000 to 2014, the UK economy had a lower proportion of GDP devoted to the investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) than the other countries of the G7. Furthermore the higher levels of productivity by country are closely correlated to their higher levels of investment.

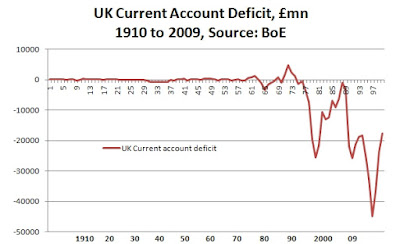

All other G7 economies gained on the UK in terms of productivity because they all had higher levels of investment over the same period. This relatively low rate of investment in Britain also accounts for the relatively weak competitiveness of the UK economy, including its large and growing external deficits.

There is a widespread fallacy that it is cheap overseas labour which drives the deterioration in the UK trade and current account balances. But 80% of British goods exports are to other industrialised economies and 70% of its imports are also from those economies. Because Britain has much lower investment and productivity than those economies it runs a substantial trade deficit with them, approximately £60 billion per annum in the most recent data.

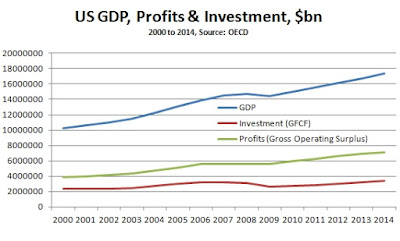

The G7 economies as a whole have allowed investment to fall as a proportion of GDP. All of the G7 economies have experienced this fall, the sole exception being Canada. But the UK economy has throughout the entire period had the lowest rate of investment of all.

The median level of G7 GFCF as a proportion of GDP has fallen from 23.7% to 19.5% in a short period, from 2000 to 2014. At the same time it has fallen in Britain from 19.9% to 17.1%. Therefore a supplementary aim should be to get the rate of investment in Britain up to the G7 average over the medium-term simply in order to prevent further declines in competitiveness.

Total cost

Osborne claims to be in favour of investment. But austerity is the latest manifestation of the neoliberal economic model which has held sway in the Western economies since Reagan and Thatcher. It is absolutely opposed to public sector investment because handing public sector assets to the private sector is a decisive means of boosting profitability. In this economic model, the means of production must be handed to private capital.

Osborne is a subscriber to this view. As a result, public sector investment has fallen dramatically. On official projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) the level of public sector investment will fall over the next three years (Table 3.6). Public sector net investment will fall to 1.4% of GDP in the last years of this parliament (Table 4.35).

As noted above the additional level of public sector investment required under a Corbyn-led government would be approximately £82 billion, or 4% of GDP in order to return to previous trends. According to the OBR the total level of net public sector investment in the current Financial Year will be £33.6 billion (Table 4.15). However, this is after the deduction of depreciation of just under £40 billion. The gross level of public sector investment in the current FY is projected to be £73.4 billion. The required investment of £82 billion is in addition to this gross total, giving a total level of public sector investment need at £155 billion.

Of course, not all of this needs to carried out by central government and still less needs to be funded by government borrowing. But this assessment is simply what is required in order to return to pre-crisis growth rates and would not even be sufficient to maintain current low levels of competitiveness versus the other countries of the G7.

Equally there will be attempts to cast this analysis as ‘extremist’ or simply ‘unrealistic’. But it is no more extreme or unrealistic than the analysis of the chief economics commentator of the Financial Times, Martin Wolf in Cameron is consigning the UK to stagnation.

“He [Jonathan Portes of the NIESR] recommends a £30bn investment programme (about 2 per cent of GDP). I would go for far more. Note that the impact on the government’s debt stock would be trivial even if it brought no longer-term gains…

‘…the government… is refusing to take advantage of the borrowing opportunities of a lifetime…. It is determined to persist with its course, regardless of the unexpectedly adverse changes in the external environment. The result is likely to be a permanent reduction in the output of the UK”.

In future posts SEB will examine where this investment should be concentrated, what its likely impact will be on growth and living standards, and how it could be funded, as well as other issues.

Recent Comments