Economist Michael Burke on Labour’s 2024 budget

Behind the Budget smoke and mirrors, there is only more austerity

By Diane Abbott MP

Budgets are accompanied by a blizzard of documentation designed to illuminate the detail of the big fiscal events. But the real effect can be to obscure what the real thrust of policy is and what its impact is.

The confusion surrounding the October 2024 Budget is even greater than usual. Essentially, what is being discussed as a huge tax-and-spend Budget is in reality, a Budget which not only extends austerity but actually deepens it.

First, let us highlight some of the things that have happened (or not) that give the lie to the idea that this is a big tax-and-spend Budget. One striking development is that the IMF has welcomed the Budget. The IMF has never supported what might be called “Keynesian” increases in taxes and public spending; it is an institution gripped by neoliberalism. But it specifically welcomes the central aim to “reduce the deficit by raising revenues.” As we shall see, the burden of that deficit reduction will be taxes on ordinary people.

Similarly, despite all the nervous chatter about how the markets would react to claims of enormous spending increases, the government bond market was largely unmoved. In effect, 10-year borrowing costs for the government are no different from those of the US government, which seems far from a crisis.

But fundamentally, any significant changes to both taxes and spending ought to have large economic impacts, as the government is the biggest single actor in the economy. Huge increases in both ought to have commensurately large economic impacts.

Yet the official forecasts are for almost no net economic impact over the next five years at all. Media outlets which continue to parrot both the size of the Budget measures and the meagreness of the economic response risk making themselves look ridiculous.

This is a pack of dogs that did not bark. The explanation is quite simple. The “huge” rise in both tax revenues and even larger rises in spending are a mirage.

In March 2024, the Tories announced huge cuts in spending and tax increases, timed to be implemented after the election, for obvious electoral reasons. These are the fiscal plans that Labour inherited.

They were so draconian it is doubtful the Tories could have implemented them without huge social unrest (as well as financial market turmoil). The Tories’ poll position suggested there was never any intent to implement them.

Comparing new tax-and-spend plans against these fictional levels does not amount to huge increases in either taxes or spending. By the same token, not imposing most of those reckless Tory cuts does not mean that austerity is ending.

The reasonable comparison is to compare the fiscal plan now with the actual outturn in the previous fiscal year 2023-24. Once the correct comparison is made, all the confusion disappears. So, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) shows that what is presented as an enormous increase in employer’s National Insurance contributions (NICs) is, in reality, nothing more than making good the big loss of government revenue by Jeremy Hunt’s cut to employees’ NICs in March.

So, before Hunt made his NICs giveaway to middle and higher earners, NICS as a whole contributed government revenues equivalent to 6.6 per cent of GDP. After Hunt’s cut, the revenues fall to 5.9 per cent of GDP. After the November Budget move on employers’ NICs, it goes back to 6.6 per cent of GDP over the next few years, a change back and forth of 0.7 per cent of GDP.

To be clear, although higher earners would not be a priority for most progressive taxation policies, the combined Hunt and Reeves moves amount to a transfer of incomes from business to workers.

However, much bigger measures, which are undoubtedly austerity, are taking place. In the same OBR documentation (table 4.1 of the Economic and Fiscal Outlook, for the economics nerds), income tax revenues will rise from 10.2 per cent of GDP to 11.6 per cent by 2028-29, a rise of 1.4 per cent of GDP.

This is double the change in employers’ NICs. It is achieved by freezing the income tax thresholds. Depending on the degree of wage inflation that takes place, this means more ordinary workers will pay some of their income at higher rates of income tax. It is a stealth tax which will clobber ordinary workers.

This is undoubtedly austerity. The same applies to departmental spending. All of it looks incredibly generous when compared to Hunt’s plans for slash and burn. But the actual picture is somewhat different, as shown by the OBR. Total managed expenditure for all government departments goes from 44.9 per cent of GDP in 2023/24 to 44.5 per cent in 2029-30 (OBR, Table 5.1). This is a tightening of government departmental spending.

It is only fair that “resource” spending does rise modestly. But the multiple crises in health, education, transport and housing are, in many cases, near a tipping point. They cannot be cured, or in some cases even ameliorated, by additional resources of 0.6 per cent of GDP. Yet this is what is on offer.

The Chancellor and the Prime Minister, in particular, argued that growth was key to improving public finances and funding sustainable improvements in public services. Public-sector investment is crucial to that, they have argued, not least in drawing in private sector investment. I largely agree with those propositions.

Yet, as we have already shown, the official real GDP forecasts over the next few years are no improvement on previous forecasts and are actually slightly lower.

This should be no surprise, as, despite all the talk, public-sector investment is not increasing. While the average annual real GDP forecast is approximately 1.5 per cent over the next few years, the government’s plans for public sector investment amount to yearly increases of about 1 per cent. In three of the next six years, public sector investment is projected to fall, and it falls as a proportion of GDP.

As a result, the government is left hoping, Micawber-like, that “something will turn up” in the world economy in the next few years to lift the dilapidating British boat. Meanwhile, the Tory plans to introduce “reforms” to the work capability system aimed at cutting the flow of people by two-thirds as well as clamping down “benefit fraud.” Austerity for disabled people has been unremitting since 2010 and is set to remain so.

The outlook is for an economy crawling along at a snail’s pace, hobbled by austerity. This means workers and the poor will continue to pay for a crisis made by others.

Diane Abbott is Labour MP for Hackney North and Stoke Newington. Follow her on X @HackneyAbbott.

The above article was originally published here by the Morning Star.

What to expect from Labour’s 2024 budget

Austerity Mark III, under a Labour government

By Michael Burke

Rachel Reeves’ statement on public finances on July 29 was the opening shots of what seems set to be a long war of renewed austerity. Just as Tory Chancellor George Osborne did in 2010, Reeves has blamed the previous government for forcing the new administration into cuts. His accusation of ‘failure to fix the roof while the sun was shining’ has become her ‘failure to fix the foundations’. But in both cases they are part of a spurious PR campaign intended to provide the mantra for a long campaign of cuts.

Yet one crucial difference remains. Successful industrial action against real cuts to pay gained huge popular support. The actual pay curbs were successfully beaten back over time and are now being reversed. The strength of the industrial action and the popular support for it was undoubtedly a factor in the last government’s unpopularity and eventual defeat. Now, a Labour government is imposing new round of austerity – but dares not include public sector pay.

Why cuts?

There is no doubt that the charge against Sunak and Hunt in particular that they ‘cooked the books’ is fully justified. As the Treasury’s own analysis (pdf) shows, the subterfuge dates back from 2021 onwards, and includes a whole series of commitments on spending which were not included in subsequent Budgets. Half of the £22bn shortfall in public finances arises from sticking to exceptionally low public sector pay forecasts, even when these had already been substantially exceeded.

However, the logic that these must be dealt with by cuts to public spending is entirely spurious. The cuts themselves are wide-ranging:

- £3.1bn in departmental budgets

- £2.4bn in winter fuel payments, adversely affecting millions of pensioners

- Planned cuts in the building of 40 hospitals

- Similar cuts for roads

To this list could be added the refusal to end the 2-child benefit limit and reneging on the promise to cap the costs of social care.

In addition, the Chancellor has been clear that that there will be more of the same in the October Budget, including on cutting welfare and investment.

There is no question that this amounts to another bout of austerity, following Thatcher’s original policies, which were later emulated by Cameron and Osborne.

But the question arises is why the government believes it will work this time around? After all, Einstein’s definition of madness is repeating the same experiment and expecting a different result.

It is worth restating that both previous bouts of austerity completely failed to generate growth and raise prosperity. Thatcher’s policies created an unemployment level of over 4 million people and was saved only by the sudden inflow of enormous North Sea oil revenues. Cameron and Osborne enjoyed no such windfall, with the result that living standards are no higher now than at the beginning of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-08.

This history holds important lessons for current policy. Both Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer have repeatedly claimed that their central economic aim is to raise the growth rate of the economy, and, from that raise average living standards and improve public services. But cuts have never delivered growth (Cameron and Osborne knew that and so started to increase public spending in 2014, ahead of the general election the following year).

The key to better public finances is growth, and anything that depresses GDP (including cuts to public spending and investment) will damage public finances. Under a previous Labour government, UK Treasury analysis codified this proposition, that growth reduces the deficit with the finding below:

“Overall a 1 per cent increase in output relative to trend after two years is estimated to reduce the ratio of public sector net borrowing to GDP by just under ¾ percentage point, while increasing the ratio of surplus on the current budget to GDP ratio by just under ¾ percentage point.” – Public Finances and Cycle, Treasury Economic Working Paper No.5, November 2008, (pdf).

In plain terms every £1 increase in GDP increases public sector receipts by over 50p, while also reducing public sector outlays by over 20p. The combined effect of the two is to improve government finances by 75p.

The government believes that growth is the answer to the current economic stagnation and is required for any improvement in public services. The conclusion of Treasury analysis points in the same direction. History shows too that prolonged bouts of austerity lower growth and mean that any improvement in public finances is extremely limited, at best.

A renewed austerity policy is in direct conflict with the stated aim of raising the growth rate.

Real and stated objectives

Massive job losses and/or real pay cuts, cuts to public services and welfare payments along with privatisations have not mainly been about public finances at all. When Callaghan/Healey first trialled them, it was claimed they were in response to a fictitious balance of payments crisis. Under Thatcher they were variously said to address money supply growth or inflation. It was only under Cameron/Osborne that the same policies were cast as addressing the (genuine) crisis of public sector finances.

When the same recipe is offered as a cure-all but is a remedy for none, it is reasonable to suggest that there is another, unstated motivation behind the policy. As these policies are combined with repeated cuts to taxes on profits, it is easy to see that the austerity policy is actually a transfer of incomes from poor to rich and from workers to businesses.

Profits are the motor force of a capitalist economy, especially an economy like Britain where so much of the economy is in the hands of the private sector. The aim of austerity is to fire up that motor by boosting profits. However, in practice that has been extremely difficult to enact, for a variety of reasons. Key among those has been the resistance of organised labour to real pay cuts.

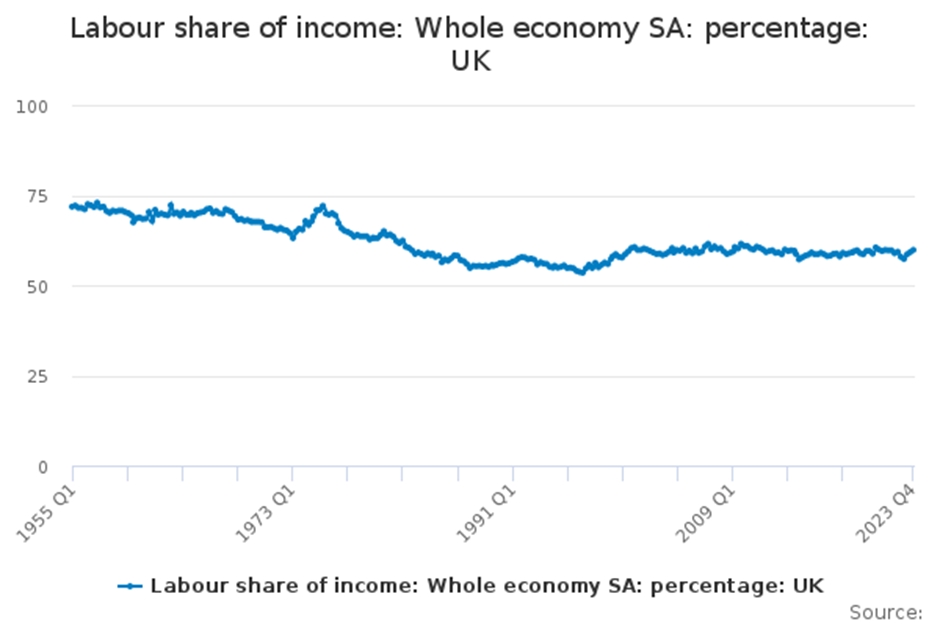

This is shown in the chart below.

Chart1. Labour share of national income, %

Source: ONS

Callaghan/Healey and then Thatcher had some success in driving down the labour share of national income and so raising the profit share. But there was a bounce-back after Britain was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1993 (which was another attempt to ‘force wage inflation out of the system’), and there it remained under Blair.

Cameron and Osborne later imposed vicious austerity and living standards have stagnated. But 14 years of austerity has produced a decline in the labour share of national income from 60.9% to 59.8% now. Put another way, austerity did shrink the growth rate of the economy towards zero and has decimated public services, but it has not remotely achieved its real objective of raising profits.

What are Starmer and Reeves hoping to achieve?

There is a fundamental departure in this initial phase of austerity under Labour compared previous episodes. There have already been small policy downpayments to cuts in investment, cuts to the infrastructure for public services and transport, as well as social welfare cuts and threats of privatisation in the form of debt-laden PFI.

Yet at the same time there are promises of pay rises above-current inflation in some parts the public sector, although it is not clear whether these will be funded with new money or from existing departmental budgets.

In some cases the suggested pay offers are way above the current rate of inflation. For example, 22% pay rises for junior doctors over 2 years may only be beginning to catch up with a loss of real pay over more than a decade. It may also be a huge exaggeration compared to what the substance of the offer is. But even if both are true, it completely contradicts all previous bouts of austerity.

In the drive to force wages down and profits up, previous governments have heavily relied on cuts or freezes to public sector pay. A variety of reasons have been given, but the aim is consistent. The public sector remains by far the biggest single employer in the country; it still employs almost 6 million workers. Austerity governments have attempted to use real pay cuts in the public sector to set a ‘going rate’ for the whole economy (economists’ jargon is a ‘demonstration effect’).

But this government has chosen a completely different course, and is supplementing inflation-plus pay rises with adjustments higher for the national minimum wage. This may even encourage pay rises in the private sector. It certainly will not depress them.

As a result, we could describe early Labour policy as social austerity, where cuts are focused on welfare spending and infrastructure. Both of these will prove highly damaging. But, for now, the new austerity does not seem to include wages in some parts of the public sector where there have been significant struggles.

Politically, there will clearly be the hope in government circles that unions will remain quiet in the face of cuts as long as pay is rising. Short-term, this could prove correct. It may allow the government to make dramatic changes to the role of the private sector in public services.

Ministers will surely hope that it will buy peace in key public services and put an end to industrial action. It should be noted that the industrial action itself has been a huge success in beating back efforts to slash real wages any keeping pay rises well below inflation. The multi-year success of the defensive action blocking real cuts to pay has now turned into a victory.

But economically it is incoherent and much-needed growth will not follow. Economic incoherence cannot be sustained.

Wages and public services can be improved through investment-led growth. Or wages too will come under the axe. One certainty is that this economic policy is unsustainable.

“Overcapacity” in Renewable Energy and EVs is a contradiction in terms

By Paul Atkin

The last few weeks have seen a series of statements, by Ursula Von Der Leyen and Janet Yellen complaining about “imbalances” caused by state investment in Chinese industry that makes competition “unfair” (von Der Leyen) and declarations that the US will not stand by while its industries are “being decimated” by Chinese imports (Yellen).

A lot of this focuses on rapidly developing green transition technologies in which China is accused of having “overcapacity”; as if the world could really do with fewer inexpensive solar panels, wind turbines and EVs.

So, the EU is launching an investigation into China’s ability to undercut EU prices in cars, steel, wind turbines, solar panels and medical devices. For example, BYD has launched an EV that retails at below E30,000, wind turbines made in China are 50% cheaper than EU models; and they offer better terms for deferred payment.

The conclusion of this should be evident to anyone who takes a passing interest. China is able to do this because it takes long term strategic decisions about what the key sectors are that need investment, and it invests in them on a large scale with a long-term consistent commitment. This approach has been derided here as “picking winners” and interfering with the unconscious genius of the market. The results of that are evident in undercapacity in the US allied countries in all these sectors.

In reality, countries such as Britain and the US provide huge subsidies to fossil fuel companies. These take the form of tax breaks for investment and opening new fields and decommissioning them. Given their costs and their destructive capacity, China’s critics are in effect picking losers.

The Chinese approach is crucial for the green transition. It is their investment that has made solar and wind more than competitive with fossil fuels and gives us the slimmest of slim chances of limiting the damage that we are already inflicting upon ourselves by transitioning too slowly. China is able to do this because, in the final analysis, it is the state not the private sector that drives strategic planning. If the EU and US (and Britain) want to catch up, they will have to do the same. Because they put the private sector first, they won’t, thereby holding the world back.

That explains why the level of investment in energy transition in China that in 2022 was already almost double that of the EU and US put together, and the gap has widened since.

Rather than rise to the level of this challenge, the EUs response is summed up by the Guardian; “The EU has been arguing that it is the largest free market in the world and that China is essentially abusing its hospitality by dumping products in Europe rather than reducing production“ (my emphasis).

So, rather than invest on a comparable scale, which is what would be necessary to get on track to meet Paris targets – because doing so would require taxation on the wealthy and big corporations and deficit financing – the EUs response is to demand that China cuts back to the inadequate levels the EU is currently capable of; thereby putting the future of the planet at risk. This is posed as “Europe will not waver from making tough decisions needed to protect its economy and security”.

This is in lockstep with the approach of the US, which has just imposed tariffs on the same sectors, among other things;

- from 25% to 100% on EVs,

- from 7.5% to 25% on lithium-ion EV batteries and other battery parts

- from 25% to 50% on photovoltaic cells used to make solar panels.

- Some critical minerals will have their tariffs raised from nothing to 25%.

More tariffs will follow in 2025 and 2026 on semiconductors, as well as lithium-ion batteries that are not used in electric vehicles, graphite and permanent magnets.

The last time the US imposed sanctions on Chinese solar panels in 2021, this did not lead to an increase in US manufacture, but the restriction in supply did lead to a jobs crisis for US workers employed to install them. This time too, the effect of these measures will be to increase costs for US consumers, restrict the supply of essential transition technologies, and therefore slow down the US transition, and that of the EU if it follows suit.

Although the United Auto Workers are arguing that these tariffs will ensure that “the transition to electric vehicles is a just transition”, and the New York Times proclaims that “China is flooding the world with car exports”, the US currently imports very few Chinese made cars (just 1.2% of its car imports in 2023; the same level as Belgium and well behind Mexico on 21%, Japan on 19%, Canada on 16.6%, South Korea on 14.9%, Germany on 11.3%, the UK and Slovakia on 3.1%, Italy on 2.4% and Sweden on 1.9%).

However, 7% of US car exports went to China in 2022. So, if you add the additional costs to US factories of the new tariffs on the 77% of the world’s lithium batteries that are manufactured in China to the inevitable tariff retaliation on US car exports to China, this will hit those exports and also domestic competitiveness. So, the impact of these tariffs on US car workers will be negative.

Hitherto, the Chinese response has been to argue that the growing demand for green tech – which has to be exponential from here on if we are to avoid the catastrophic 2.5 C increase in global temperatures that is now the average prediction among IPCC scientists – means that there will be more than enough work to be done for all economies: and that this should be approached, according to President Xi, with “strategic partnership” involving “dialogue, cooperation, trust and conscious coordination”.

This is also relevant to the economic and political course likely to be pursued by the UK under a Starmer government.

In her Mais lecture, Rachel Reeves argued that the economic stagnation of the UK economy since 2008, and regression in the last few years, can be overcome with “vision, courage and responsible government”, which sounds like an act of will in place of policy, wedded to “new economic thinking shaping governments in Europe, America and around the world”. She has codified this hitherto as “Bidenomics” or, more lately, “Securonomics”, both of which come down to support for a greater government industrial activism. However, the commitment to a £28 billion a year investment in green transition that was the core of that has been gutted; leaving little more than is already pencilled in by the Conservatives.

This leaves little more than the slogan and the act of will; which won’t go very far. A recent report from Nicholas Stern and others published by the LSE spelled out the need for the UK to invest an additional 1% of GDP – doubling its current level – in infrastructure to stop it falling behind the EU and US. Keeping up with China has long gone over the horizon. 1% of GDP amounts to £26 billion. A failure to do this will result in continued decline of the public realm, a failure to make the transition we need and a continuation of the impoverishment of the population that has led Labour focus groups to describe the state of the economy as “damaged”, “fragile” and “unbalanced”.

In relation to the car industry, if the Chinese EV manufacturers are indeed the most efficient and cheapest and, contrary to Western myths, technologically ahead (with no need to “steal” intellectual property that it is already beyond) then the surest course to preserve motor manufacturing in the UK would be to seek investment here from those companies.

The £1.2 billion that Chinese battery firm EVE is planning to invest in a gigafactory outside Coventry, creating 6,000 jobs, is an indication of what might be possible; so long as there is not a deepening of the economic self-harm already seen in the removal of Huawei from 5G provision and CGM from Sizewell C on “security” grounds; helping create political tensions and drum up the war drive that will make everyone in the world far less “secure” and cut off that potential supply of investment.

The recovery is a mirage – It is simply a pre-election government bribe

By Michael Burke

The latest British GDP data are being hailed not just as the end of the recession but as the beginning of a strong recovery. These are widespread evaluations, but they are evidence-free. The actual data show that the private sector of the economy remains in recession. Instead, there is a splurge in government spending, both Consumption and Investment. This is not sustainable with current economic policies and structures, and the government’s own forecasts show they have no intention of continuing beyond the election.

The British economic situation is chiefly characterised by prolonged stagnation. This is primarily driven by weak private sector investment which is creating falling living standards on broadening horizon. Structurally weak private investment has recently been temporarily boosted by tax breaks, as will be shown. The government response in an election year is to make up the shortfall in the hope it will take it through to the election date.

The medium-term stagnation of the economy is clear from the fact that real GDP is now just 1.6% higher than the pre-pandemic peak in the 3rd quarter of 2019, 4½ years ago. At the same time, as a result of negative redistribution, from poor to rich, average living standards (GDP per head) are now 1.3% below their pre-pandemic peak. All of this is driven by weak business investment which is just 3.1% higher than its previous peak in the 3rd quarter of 2016, 7½ years ago. It is clear from these data alone that the fundamental trends in the British economy have not been altered by the latest quarterly data.

Private Sector Remains in Recession

But the contrast between the claims of recession end and an accurate analysis becomes quite stark once the data is examined in greater detail and the factual trends are revealed. Grant Fitzner, the chief economist for Office for National Statistics (ONS) was widely quoted as saying the economy is now “going gangbusters”. The reality is quite different.

In the first instance, it is impossible to examine real trends by highlighting the change in economic activity from one quarter to the next. The year-on-year date is much more useful, because more accurate in that light. On that measure, real GDP rose by just 0.2% in the 1st quarter of 2024, effectively a continuation of stagnation.

However, examining the sources of spending that comprise GDP shows a remarkable picture, completely undermining any idea that a self-sustaining recovery has begun. In effect, almost every major category of spending is contracting, the sole exception being Government spending.

Table 1 shows the changes in key components of real GDP in the 1st quarter. For completeness the changes are shown on the basis of both quarter-on-quarter and year-on-year terms.

Table 1. Changes in Real GDP and its components in 1st quarter 2024

| GDP | Household Consumption | Government Consumption | Investment (GFCF) | -of which Business Investment | Exports | Imports | |

| Q-on-Q | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 | -1.0 | -2.3 |

| Year-on-Year | 0.2 | -0.4 | +3.7 | -0.3 | -0.6 | -2.1 | -2.7 |

Source: ONS National Accounts, Q1, first estimate, Table C2

In addition to its role in the economy through Consumption, the government also plays a significant role in Investment, although usually Gross Fixed Capital Investment (GFCF) is presented as a total, with Government Investment included in that total. As can be seen from Table 1, Business Investment (which accounts for the bulk of GFCF) fell faster than total GFCF in the 1st quarter.

In fact, general Government GFCF rose by 9.5% from a year ago in the 1st quarter. This magnifies the role that the public sector has played in boosting GDP. Inevitably, it also reduces further the role played by the private sector in rebound in GDP in the 1st quarter.

Chart 1. Below shows the recent trends in GDP and the main expenditure components. As can be seen, Business Investment has previously been stronger, based on tax breaks given to businesses which encouraged them to bring forward investment. This has now petered out and has become negative, along with other private sector expenditure (separately, both exports and imports are declining from a year ago). Only Government Consumption and Investment show a rising trend.

Chart 1. UK Real GDP and Expenditure Components, Q4 2022 to Q1 2024, % change y-o-y

These diametrically opposed trends in the public and private sectors becomes evident when examined in monetary terms. In year-on-year comparisons, real GDP rose by £1.169bn. The combined level of Government Consumption and Investment (GFCF) rose by £6.295bn over the same period. The private sector (including the statistically tiny non-profit sector) contracted by £5.126bn on the same basis. These are shown in Chart 2., below.

Chart 2. Real GDP and Public and Private Sector Sources, Q4 2022 to Q4 2024, change £bn

A Political Splurge of Spending

SEB has long argued for both an increase in Government Investment and Consumption as the alternative to austerity, although it has placed much more emphasis on Investment than others. That is because without an expansion in the means of production through Investment, it is not possible to sustain increases in Consumption. From ancient times farmers have understood that the greater proportion of this year’s crop preserved (Saving) for sowing next year (Investment) the greater the next crop will be, all other things being equal. Unfortunately, this is largely forgotten in modern neoliberal, and other Consumption-based economics.

But the conditions do not exist to allow this type of increase in Government spending to be sustained. First, from tax breaks to companies who respond by cutting Business Investment, to ignoring the effects of climate change, to stupid and reactionary spending on the military and deportation policies, a large proportion of the recent increase in Government Consumption is either wasteful or actually counter-productive. There is a huge misallocation of resources.

Secondly, given the acute requirement to adopt an Investment-led recovery programme which also tackles the crisis in public services, there is simply not the tax structure in the British economy to sustain this splurge in spending. The tax burden falls overwhelmingly on those who can least afford it, workers and the poor, and not on those who can, big business and the rich. This would need to be reversed to generate the tax revenues required.

Thirdly, the government itself does not intend to sustain either rising Investment or Consumption. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts for government spending and its components are based on briefings from government departments about ministerial intentions. The government plans to cut both its own Consumption and Investment next year, if re-elected.

Excluding the welfare bill (which must rise because of an ageing population) the OBR estimates (pdf Table 4.4) that combined Government Consumption and Investment outlays will be cut in real terms by 7.1% by the end of the next parliament compared to the fiscal year just ended in April 2024. The government has no intention of sustaining these increases in spending and could not sustain them without a radical transformation of fiscal policy.

In 2014 and 2015 the Osborne/Cameron-led Coalition increased both government Investment and Consumption in the run-up to the 2015 election. It was a pre-election giveaway which worked, and they promptly slashed both once re-elected. Sunak and Hunt may be hoping to repeat the trick. The data certainly suggests that.

It would also be no surprise then to see the spending splurge continue all the way through to the election. But, extending unsustainable Government spending does not make it sustainable. Like any sugar rush, the comedown will only be harder the longer the binge continues.

The government is attempting to bribe its way to election victory, or least limit the scale of their losses. As this rise in spending is not sustainable, for the reasons shown above, the greater will be the next planned round of austerity after the election.

The economic case for Irish unification, once again

Recent well-publicised analysis has cast doubt on the sustainability or affordability of a United Ireland economy, arguing that it would cost taxpayers in the Irish Republic up to €20bn per year.

Below we reproduce an article, which first appeared on the Slugger O’Toole website in 2015, which attempts to address these long-standing arguments in a popular fashion.

For readers with a close interest in the topic, a much more detailed argument is presented here, also from 2015.

* * * * *

Growth and the ‘subvention’

By Michael Burke

The economic case for Irish unity is a growth story; that people across the whole of the island would be substantially better off. So, as the author of a recent report, the Economic Case for Irish Unity, I was disappointed but not surprised to find that most commentary on it related to the issue of the ‘subvention’.

Apparently, supporters of the Union want to make the case that the NI economy, which has always been part of the UK, is such a basket-case that there is no future for it except as a subsidy-junkie; Stockholm syndrome economics. Fortunately, this caricature is not accurate. But it does mean that the outlandish assertions on the subvention do need to be addressed.

In my own report (and previously on Slugger) I have offered Office for National Statistics data on the scope of the household subvention. To repeat, these are official ONS data not my own. These show that that the entire net effect of all direct and indirect taxes and benefits (including social security, pensions, education, health spending and so on) is an average transfer of £981 per household in NI. As there are 739,000 households this means that the total household subvention is approximately £700 million per annum. Again, in an effort to reduce the silliness about the provenance of the data, here is the entire ONS report.

£700 million is not nothing. But it doesn’t suggest NI is a basket-case either. Of course there are other elements of government spending, but it is this household net transfer (‘subvention’) which people have in mind when making assertions about the dis/benefits of the Union for the population of NI.

As well as other elements of government spending there are also other sources of government revenue, primarily the tax and National Insurance contributions from businesses. In order to gauge the net effect of these it would be necessary to compile them all.

Unfortunately, the Department for Finance and Personnel (DfP) efforts in this regard are woefully inadequate. The DfP claims that its own ‘Net Fiscal Balance Reports’ are comparable to the Government Expenditure and Revenue in Scotland (‘GERS’). This is simply untrue. Again, this is not personal verdict, but that of the main statistical body in the UK, the ONS. The ONS treats GERS as official data, a status it does not accord to the DfP’s efforts, with good reason.

To take one example of expenditure, much of the notional allocation of capital investment is simply done by DfP on a per capita proportion of the UK total. No data on public sector net investment is published for NI. But Crossrail in London costs £15 billion and HS2 is said to cost £40 billion, the new nuclear power stations at Hinckley Point will be more expensive still, and so on. On DfP methodology the ‘subvention’ will include an allocated share of these costs. The true picture is shown in the Coalition government’s £200 billion ‘National Infrastructure Plan’ in 2010 – there is nothing down for NI at all.

Further, the gaps in the revenue side render the DfP report valueless. In Table 3.7 of the latest report, of 28 revenue categories either the DfP or HMRC has no estimate for 12 of them. The ONS is right to withhold official status from the DfP reports. Yet the entire outlandish case on the ‘subvention’, and all the repetitions of it, are built on them.

The only hard data on the ‘subvention’ is provided by the ONS on the household component, which amounts to just £700 million. Perhaps, if all other items of government expenditure were also included (defence, civil service, state bodies, capital investment, interest, etc.), alongside the government revenues from the business sector (NICs, corporation tax, CGT, a small proportion of VAT, etc.) then the UK deficit was approximately £72 billion in 2013/14. A crude per capita allocation of that for NI would mean its share was £2.25 billion. This is an extremely crude method – but exactly the same as DfP’s.

Unfortunately, all the wild and foolish claims made on the subvention bring us no nearer to an understanding of the benefits and challenges of a unified Irish economy. This is because no serious economist would begin by asking what the fiscal implications of Irish unity would be without asking first about the growth implication. The fiscal position of any economy is determined primarily by its growth.

At the time of the founding of this state no country in Europe had a higher standard of living than Britain and NI. Now, half a dozen or more do. Britain is in a long-term relative economic decline and the economy in NI has fared even worse. It is the semi-detached carriage of a very slow-moving train.

A unified Irish economy provides the basis for an entirely new economy, marrying efficient public services with a dynamic multinational sector and requiring strategic public investment. In a growing economy the deficit takes care of itself.

The Tory Spring Budget and the Labour Response – video

Economist Michael Burke explains the Tory Spring Budget: an agenda for more austerity, with no Labour alternative.

Economic policy is set for even more austerity – video

Economist Michael Burke explains the Tory Government’s 2024 Spring Budget

China’s economy is still far out growing the U.S. – contrary to Western media “fake news”

By John Ross

GDP data for China, the U.S., and the other G7 countries for the year 2023 has now been published. This makes possible an accurate assessment of China’s, the U.S., and major economies performance—both in terms of China’s domestic goals and international comparisons. There are two key reasons this is important.

First for China’s domestic reasons: to achieve a balanced estimate of China’s socialist economic situation and therefore the tasks it faces.

Second, because the U.S. has launched a quite extraordinary propaganda campaign, including numerous straightforward factual falsifications, to attempt to conceal the real international economic facts.

The factual situation is that China’s economy, as it heads into 2024, has far outgrown all other major comparable economies. This reality is in total contradiction to claims in the U.S. media. This in turn, therefore, demonstrates the extraordinary distortions and falsifications in the U.S. media about this situation. It confirms that, with a few honourable exceptions, Western economic journalism is primarily dominated by, in some cases quite extraordinary, “fake news” rather than any objective analysis. Both for understanding the economic situation, and the degree of distortion in the U.S. media, it is therefore necessary to establish the facts of current international developments.

China’s growth targets

Starting with China’s strategic domestic criteria, it has set clear goals for its economic development over the next period which will complete its transition from a “developing” to a “high-income” economy by World Bank international standards. In precise numbers, in 2020’s discussion around the 14th Five Year plan, it was concluded that for China by 2035: “It is entirely possible to double the total or per capita income”. Such a result would mean China decisively overcoming the alleged “middle income trap” and, as the 20th Party Congress stated, China reaching the level of a “medium-developed country by 2035”.

In contrast, a recent series of Western reports, widely used in anti-China propaganda, claim that China’s economy will experience sharp slowdown and will fail to reach its targets.

Self-evidently which of these outcomes is achieved is of fundamental importance for China’s entire national rejuvenation and construction of socialism—as Xi Jinping stated, China’s: “path takes economic development as the central task, and brings along economic, political, cultural, social, ecological and other forms of progress.” But the outcome also affects the entire global economy—for example, a recent article by the chair of Rockefeller International, published in the Financial Times, made the claim that what was occurring was China’s “economy… losing share to its peers”. The Wall Street journal asserted: “China’s economy limps into 2024” whereas in contrast the U.S. was marked by a “resilient domestic economy.” The British Daily Telegraph proclaimed China has a “stagnant economy”. The Washington Post headlined that: “Falling inflation, rising growth give U.S. the world’s best recovery” with the article claiming: “in the United States… the surprisingly strong economy is outperforming all of its major trading partners.” This is allegedly because: “Through the end of September, it was more than 7 percent larger than before the pandemic. That was more than twice Japan’s gain and far better than Germany’s anaemic 0.3 percent increase.” Numerous similar claims could be quoted from the U.S. media.

U.S. use of “fake news”

Reading U.S. media claims on these issues, and comparing them to the facts it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that what is involved is deliberate “fake news” for propaganda purposes—as will be seen, the only alternative explanation is that it is disgracefully sloppy journalism that should not appear in supposedly “quality” media. For example, it is simply absurdly untrue, genuinely “fake news”, that the U.S. is “outperforming all of its major trading partners”, or that China has a “stagnant economy”. Anyone who bothers to consult the facts, an elementary requirement for a journalist, can easily find out that such claims are entirely false—as will be shown in detail below.

To first give an example regarding U.S. domestic reports, before dealing with international aspects, a distortion of U.S. economic growth in 2023 was so widely reported in the U.S. media that it is again hard to avoid the conclusion that this was a deliberate misrepresentation to present an exaggerated view of U.S. economic performance. Factually, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the U.S. official statistics agency for economic growth, reported that U.S. GDP in 2023 rose by 2.5%—for comparison China’s GDP increased by 5.2%. But a series of U.S. media outlets, starting with the Wall Street Journal, instead proclaimed that the “U.S. economy grew 3.1% over the last year”.

This “fake news” on U.S. growth was created by statistical “cherry picking”. In this case comparing only the last quarter of 2023 with the last quarter of 2022, which was an increase of 3.1%, but not by taking GDP growth in the year as a whole “last year”. But U.S. growth in the earlier part of 2023 was far weaker than in the 4th quarter—year on year growth in the 1st quarter was only 1.7% and in the 2nd quarter only 2.4%. Taking into account this weak growth in the first part of the year, and stronger growth in the second, U.S. growth for the year as a whole was only 2.5%—not 3.1%. As it is perfectly easy to look up the actual annual figure, which was precisely published by the U.S. statistical authorities, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this was a deliberate distortion in the U.S. media to falsely present a higher U.S. growth rate in 2023 than the reality.

It may be noted that even if U.S. GDP growth had been 3.1% then China’s was much higher at 5.2%. But the real data makes it transparently clear that China’s economy grew more than twice as fast as the U.S. in 2023—showing at a glance that claims that the U.S. is “outperforming all of its major trading partners”, or that China has a “stagnant economy” were entirely “fake news”.

Many more examples of U.S. media false claims could be given, but the best way to see the overall situation is to systematically present the overall facts of growth in the major economies.

What China has to do to achieve its 2035 goals

Turning first to assessing China’s economic performance, compared to its own strategic goals of doubling GDP and per capita GDP between 2020 and 2035, it should be noted that in 2022 China’s population declined by 0.1% and this fall is expected to continue—the UN projects China’s population will decline by an average 0.1% a year between 2020 and 2035. Therefore, in economic growth terms, the goal of doubling GDP growth to 2035 is slightly more challenging than the per capita target and will be concentrated on here—if China’s total GDP goal is achieved then the per capita GDP one will necessarily be exceeded.

To make an international comparison of China’s growth projections compared with the U.S., the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), responsible for the official growth projections for the U.S. economy on which its government’s policies rely, estimates there will be 1.8% annual average U.S. GDP growth between 2023 and 2033—with this falling to 1.6% from 2034 onwards. This figure is slightly below the current U.S. 12-year long term annual average GDP growth of 2.3%—12 being the number of years from 2023 to 2035. To avoid any suggestion of bias against the U.S., and in favour of China, in international comparisons here the higher U.S. number of 2.3% will be used.

The results of such figures are that if China hits its growth target for 2035, and the U.S. continues to grow at 2.3%, then between 2020 and 2035 China’s economy will grow by 100% and the U.S. by 41%—see Figure 1. Therefore, from 2020 to 2035, China’s economy would grow slightly more than two and a half times as fast as the U.S.

FIgure 1

The strategic consequences of China’s economic growth rate

The international implications of any such growth outcomes were succinctly summarised by Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times. If China’s economy continues to grow substantially faster than Western ones, and it achieves the status of a “medium-developed country by 2035”, then, in addition to achieving high domestic living standards, China’s will become by far the world’s largest economy. As Wolf put it: “The implications can be seen in quite a simple way. According to the IMF, China’s gross domestic product per head (measured at purchasing power) was 28 per cent of U.S. levels in 2022. This is almost exactly half of Poland’s relative GDP per head… Now, suppose its [China’s] relative GDP per head doubled, to match Poland’s. Then its GDP would be more than double that of the U.S. and bigger than that of the U.S. and EU together.” By 2035 such a process would not be completed on the growth rates already given, and measuring by Wolf’s chosen measure of purchasing power parities (PPPs) China’s economy by 2035 would be 60% bigger than that of the U.S. But even that would make China by far the world’s largest economy.

Wolf equally accurately notes that the only way that such an outcome would be prevented from occurring is if China’s economy slows down to the growth rate of a Western economy such as the U.S. Clearly, if China’s economic growth slows to that of a Western economy, then, naturally, China will never catch up with the West—it will necessarily simply stay the same distance behind. Therefore. as Wolf accurately puts it the outcomes are:

What is the economic future of China? Will it become a high-income economy and so, inevitably, the largest in the world for an extended period, or will it be stuck in the ‘middle income’ trap, with growth comparable to that of the U.S.?

The progress in achieving China’s strategic economic goals

Turning to the precise figure required to achieve China’s 2035 target, China’s goal of doubling GDP required average annual growth of at least 4.7% a year between 2020 and 2035. So far China, as Figure 1 shows, is ahead of this goal—annual average growth in 2020-2022 was 5.7%, meaning that from 2023-2035 annual average 4.6% growth is now required.

China’ 5.2% GDP increase in 2023 therefore once again exceeded the required 4.6% growth rate to achieve its 2035 goal—as shown in Figure 1. From 2020 to 2023 the required total increase in China’s GDP to hit its 2035 target was 14.9%, whereas in fact its growth was 17.5%. This is in line with the 45-year record since 1978’s Reform and Opening Up, during which entire period the medium/long term targets set by China have always been exceeded.

Therefore, to summarise, there is no sign whatever in 2023, or indeed in the period since 2020, that China will fail to meet its target of doubling GDP between 2020 and 2035—China is ahead of this target. Such a 4.6% growth rate would easily ensure China becomes a high-income economy by World Bank criteria well before 2035—the present criteria for this being per capita income of $13,846.

It should be noted, as discussed in in detail below, that a clear international conclusion flows from this necessary 4.6% annual average growth rate for China to achieve its strategic goals. It means that China must continue to grow much faster than the Western economies throughout this period to 2035—that is in line with China’s current trend. However, if China were to slow down to the growth rate of a Western economy, then it will fail to achieve its strategic goals to 2035, may not succeed in becoming a high income economy, and will necessarily remain the same distance behind the West as now. The implications of this will be considered below.

Systematic comparisons not “cherry picking”

Having considered China’s performance in 2023 in terms of achieving its own domestic strategic goals we will now turn to actual results and a comparison of China with other international economies. This immediately shows the factual absurdity, the pure “fake news” of claims such as that the U.S. has “the world’s best recovery“ and “the United States… is outperforming all of its major trading partners.” On the contrary China has continued to far outgrow the U.S. economy not only in 2023 but in the entire last period. China’s outperformance of the other major Western economies, the G7, is even greater that of the U.S.

Entirely misleading claims regarding such international comparisons, used for propaganda as opposed to serious analysis, are sometimes made because data is taken from extremely short periods of time which are taken out of context—unrepresentative statistical “cherry picking” or, as Lenin put it, a statistical “dirty business”. Such a method is always erroneous, but it is particularly so during periods which were affected by the impact of the Covid pandemic as these caused extremely violent short-term economic fluctuations related to lock downs and similar measures. China’s assertion of superior growth is based on its overall performance, not an absurd claim that it outperforms every other economy, on every single measure, in every single period! Therefore, in making international comparisons, the most suitable period to take is that for since the beginning of the pandemic up to the latest available GDP data. As comparison of China with the U.S. is the most commonly made one, and particularly concentrated on by the U.S. media campaign, this will be considered first.

China’s and the U.S.’s growth in 2023

It was already noted that in 2023 China’s GDP grew by 5.2% and the U.S. by 2.5%—China’s economy growing more than twice as fast as the U.S. But it should also be observed that 2023 was an above trend growth year for the U.S.—U.S. annual average growth over a 12-year period is only 2.3% and over a 20-year period it is only 2.1%. Therefore, although in 2023 China’s economy grew more than twice as fast as the U.S., that figure is actually somewhat flattering for the U.S. Figure 2 shows that in the overall period since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy has grown by 20.1% and the U.S. by 8.1%—that is China’s total GDP growth since the beginning of the pandemic was two and half times greater than the U.S. China’s annual average growth rate was 4.7% compared to the US’s 2.0%.

Figure 2

Economic performance of China and the three major global economic centres

Turning to wider international comparisons than the U.S. such data immediately shows the extremely negative situation in most “Global North” economies and China’s great outperformance of them. To start by analysing this in the broadest terms, Figure 3 shows the developments in the world’s three largest economic centres—China, the U.S., and the Eurozone. These three together account for 57% of world GDP at current exchange rates and 46% in purchasing power parities (PPPs). No other economic centre comes close to matching their weight in the world economy.

Regarding the relative performance of these three major economic centres, at the time of writing data has not been published for the Euro Area for the whole year of 2023 —which would be the ideal comparison. However, it has been published for the Euro area for the four quarters of 2023 individually and trends can be calculated on that basis. These show that in the four years to the 4th quarter of 2023, covering the period since the beginning of the pandemic, China’s economy has grown by 20.1%, the U.S. by 8.2%, and the Eurozone by 3.0%. China’s economy therefore grew by two and a half times as fast as the U.S. while the situation of the Eurozone could accurately be described as extremely negative with annual average GDP growth in the last four years of only 0.7%.

Such data again makes it immediately obvious that claims in the Western media that China faces economic crisis, and the Western economies are doing well is entirely absurd—pure fantasy propaganda disconnected from reality.

Figure 3

Relative performance of China and the G7

Turning to analysing individual countries, then comparing China to all G7 states, i.e. the major advanced economies, shows the situation equally clearly—see Figure 4. Data for China and all G7 economies has now been published for the whole of 2023. The huge outperformance by China of all the major advanced economies is again evident.

Over the four years since the beginning of the pandemic China’s economy grew by 20.1%, the U.S. by 8.1%, Canada by 5.4%, Italy by 3.1%, the UK by 1.8%, France by 1.7%, Japan by 1.1% and Germany by 0.7%.

In the same period China’s economy therefore grew two and a half times as fast as the U.S., almost four times as fast as Canada, almost seven times as fast as Italy, 11 times as fast as the UK, 12 times as fast as France, 18 times as fast as Japan and almost 29 times as fast as Germany.

In terms of annual average GDP growth during this period China’s was 4.7%, the U.S. 2.0%, Canada 1.3%, Italy 0.8%, the UK 0.4%, France 0.4%, Japan 0.3% and Germany 0.2%.

It may therefore be seen that China’s economy far outperformed the U.S., while the performance of all other major G7 economies may be quite reasonably described as extremely negative—all having annual average economic growth rates of around or even under 1%.

Figure 4

Comparison of China to developing economies

A comparison using the IMF’s January 2024 projections can also be made to the major developing economies—the BRICS. Figure 5 shows this, using the factual result for China and the IMF projections for the other countries. Over the period since the start of the pandemic, from 2019-2023, China’s GDP grew by 20.1%, India by 17.5%, Brazil by 7.7%, Russia by 3.7% and South Africa by 0.9%.

This data confirms that the major Global South economies are growing faster than most of the major Global North economies, which is part of the rise of the Global South and draws attention to the good performance of India. But China grew more than two and half times more than all the BRICS economies except India—China’s growth was 15% greater than India’s. It should be noted that India is at a far lower stage of development than the other BRICS economies—all the others fall in the World Bank classification of upper middle-income economies whereas India falls into the lower middle income group.

Figure 5

Comparison of China’s growth to Western economies

Finally, this outperformance by China casts light on what is necessary to achieve its own 2035 strategic targets. China’s 4.6% growth rate necessary to meet these goals means that it must continue to maintain a growth rate far higher than Western economies—Figure 6 shows this in overall terms in addition to individual comparisons given to major economies above. Whereas China must achieve an annual average 4.6% growth rate the median growth rate of high income “Western” economies is only 1.9%, the U.S. is 2.3%, and the median for developing economies is 3.0%. That is, to achieve its 2035 goals China must grow twice as fast as the long term trend of the U.S., almost two and a half times as fast as the median for high income economies, and more than 50% faster than the median for developing economies. As already seen, China is more than achieving this.

But such facts immediately show why it is an extremely misleading when proposals are made that China should move towards the macro-economic structure of a Western economy. If China adopts the structure of a Western economy then, of course, China will slow down to the same growth rate as Western economies—and therefore fail to achieve its 2035 economic goals. China will be precisely stuck in the negative outcome of the situation accurately diagnosed by Martin Wolf.

What is the economic future of China? Will it become a high-income economy and so, inevitably, the largest in the world for an extended period, or will it be stuck in the ‘middle income’ trap, with growth comparable to that of the U.S.?

Figure 6

Conclusion

In conclusion, in addition to objectively analysing 2023’s economic results, it is also necessary in the light of this factual situation to make a remark regarding Western, in particular U.S. “journalism”.

None of the data given above is secret, all is available from public readily accessible sources. In many cases it does not even require any calculations and simply published data can be used. But the U.S. media and journalists report information that is systematically misleading and in many cases simply untrue. While it lagged China in creating economic growth the U.S. was certainly the world leader in creating “fake economic news”! What was the reason, what attitude should be taken to it?

First, to avoid accusations of distortion, it should be stated that there were a small handful of Western journalists who refused to go along with this type of distortion and fake news. For example Chris Giles, the Financial Times economics commentator, in December, sharply attacked “an absurd way to compare economies… among people who should know better.” Giles did not do this because of support for China but because, quite rightly, he warned that spreading false or distorted information led to serious errors by countries doing so: “Coming from the UK, which lost its top economic dog status in the late 19th century but still has some delusions of grandeur, I can understand American denialism… But ultimately, bad comparisons foster bad decisions.” But the overwhelming majority of U.S. and Western journalists continued to spread fake news. Why?

First, the fact that identical distortions and false information appeared absolutely simultaneously across a very wide range of media makes it clear that undoubtedly U.S. intelligence services were involved in creating it—i.e. part of the misrepresentation and distortions were entirely deliberate and conscious, aimed at disguising the real situation.

Second, another part was merely sloppy journalism—that is journalists who could not be bothered to check facts.

Third, supporting both of these factors was “white Western arrogance”—an arrogant assumption, rooted in centuries of European and European descended countries dominating the world, that the West must be right. Therefore, such arrogance made it impossible to acknowledge or report the clear facts that China’s economy is far outperforming the West.

But whether it was conscious distortion, sloppy journalism, or conscious or unconscious arrogance, in all these cases no respect should be given to the Western “quality” media. It is not trying to find out the truth, which is the job of journalism, it is simply spreading false propaganda.

It remains a truth that if a theory and the real world don’t coincide there are only two courses that can be taken. The first, that of a sane person, is to abandon the theory. The second, that of a dangerous one, is to abandon the real world—precisely the danger that Chris Giles pointed to. What has been appearing in the Western media about international economic comparisons regarding China is precisely abandonment of the real world in favour of systematic fake news.

This is a shortened version of an article that originally appeared in Chinese at Guancha.cn.

About John Ross

John Ross is a senior fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He was formerly director of economic policy for the mayor of London.

The above article was originally published here by Monthly Review.

Recent Comments