The Greek Crisis

By Michael Burke

The Greek economic and social crisis continues to unfold. Around it a series of myths have arisen and been perpetuated. It is necessary first to dispose of some of those myths before moving onto a concrete analysis of the situation.

The present author has a piece in the Guardian‘s Comment Is Free web blog which addresses some of these issues. The present article will deal with rebutting those myths in slightly greater detail before setting out an alternative policy that could both resolve the Greek crisis and reconstitute the European Union and Euro Area on a more stable basis.

Greek Mythology

When the European and international authorities announced over a year ago that there would be a €110bn rescue package for Greece it was claimed that this would be sufficient for the Greek government until at least 2013, at which time the newly-restored health of the Greek economy would allow it to return to international financial markets – especially since it would by then have a far lower borrowing requirement. This rebound in activity would arise from the policies implemented by the Greek government under instruction from the EU/IMF/ECB. On all these fronts, the claims have been shown to be false and the policy a failure.

The EU/IMF/ECB is frequently described as the ‘troika’. The troika have produced a conditional emergency lending programme of €12bn because the €110bn is being rapidly consumed. Greece’s economy has gone into a tail-spin. GDP in the first quarter of 2011 is 5.5% lower than in the same period in 2010, and the rise in output from the fourth quarter of 2010 is entirely accounted for by a collapse in import demand. As a result the public sector deficit has been on a widening and not a narrowing trend. Because of the troika’s policies, the budget deficit has widened to €10.3bn in the first five months of this year, compared to €9.1bn in 2010 before those policies took effect.

It is widely reported that the further emergency funds are required because Greece has missed targets set by the troika. The targets have been missed, but only by a cumulative €1.2bn over five months. Neither this shortfall nor the total €10.3bn deficit level can explain the need for additional funds over and above the €110bn already available.

The capital which was injected has been consumed by the holders of Greek government debt, both short and long-term. As these debt obligations have been redeemed on their due date international investors have simply taken the money. They have not bought any newly issued Greek debt with the proceeds. This redemption of bond holdings has combined with continuing interest payments on the outstanding debts for a total payment to bondholders of over €40bn since the bailout was announced in May last year.

The bailout was therefore one for private creditors – primarily European (including British) and US banks. This was both predicted and predictable, with the FT’s chief economics commentator Martin Wolf noting at the time that the impositions on Greece were worse even than those on Argentina, because the private creditors were being paid to exit the market.

Furthermore, it should be noted that, while the budget deficit has not at all driven the need for extra funds, the €1.2bn overshoot is entirely a function of the collapse in tax revenues, not government overspending. In fact spending is €0.7bn lower than the EU/IMF impositions, but tax revenues are also lower by €1.9bn. This too was predicted, including by SEB.

This reality has not prevented widespread media reports that it is the widening public sector deficit which is the cause of the renewed financial crisis , even that this reflects recent overspending, which is factual nonesense.

This latter point is supplemented by the assertion, applauded by sections of the Greek right wing intelligentsia, that the underlying cause of the crisis is a ‘bloated public sector’. In fact Greek public spending before the crisis in 2007 was 46.3% of GDP, compared to 46% for the Euro Area as a whole. Greece has among the lowest proportions of public spending on both health and education in the Euro Area, while more than half of the concealed government spending in 2000-2003 was on the military – 5.5% of GDP in total.

Added to all this is the campaign to end any further payments to Greece, with Cameron declaring ‘not a penny more’ – so joining the charge led by Boris Johnson and George Osborne and including the reactionary nationalist True Finn party, all of whom ignore the small matter that ‘Greece’ is not the beneficiary of the funds to date. Its creditors are and these include British banks.

To avoid addressing the real dynamics of the situation, the mythology in both Britain and Germany also sinks to reinforcing insulting and wholly untrue stereotypes about the lazy Greeks. In fact, Greeks have the second-longest working hours in the whole of the EU.

Debt Sustainability

Now let us turn to assessing the actual dynamics unfolding in the crisis as well as the likely or preferred policy outcomes.

There is a growing consensus that a debt default by Greece is inevitable. Economists have developed a series of metrics in an attempt to determine where a specific level of debt is sustainable. An influential study from Professors Reinhart and Rogoff is widely quoted that for advanced economies output will slow markedly when the public debt level exceeds 90% of GDP . But this is not substantiated by the post-World War II experience where a host of countries had debt levels for in excess of that. Britain’s debt level exceeded 250% yet the growth in GDP in the last 10 years has been little over half that of the 10 years from 1948 onwards.

A more sophisticated and robust measure of debt sustainability is as follows: the real interest rate minus the real growth rate multiplied by the debt/GDP ratio must be lower than the primary budget balance (primary, meaning before debt interest payments are included).

In a less technical formulation of the same proposition; the economy must be able to grow it way out of the debt. However, if total interest payments rise at a faster rate than GDP growth, the debt burden becomes unsustainable.

In the case of Greece currently interest rates (borrowing from the EU/IMF at approximately 6%) exceed the growth rate (-5.5%) by 11.5%. The debt/GDP ratio is 158%, according to Eurostat. This means the interest burden is 18.17 (11.5 multiplied by 1.58) whereas the primary budget balance is forecast by Eurostat to be a deficit of 2.8% of GDP in 2011. The primary surplus would need to rise by 21% of GDP to be sustainable, effectively that government spending would have to be halved without any detrimental effects on the economy or on taxation revenues.

However, the detrimental effects of far more modest cuts- at least compared to this projected level – have already been so great as to overwhelm any supposed ‘savings’. There is no reason to suppose that cuts of an even greater magnitude will have any other effect. Yet this is the prescription demanded by the EU/IMF/ECB.

Under these policy settings a Greek default seems inevitable. (Using the same metrics and applying the Eurostat data and forecasts in each case, Irish and Portuguese defaults are also unavoidable, without a change of policy).

A Progressive Approach

On current trends for the year to date, the Greek public sector deficit could reach €24bn. However, in common with nearly all advanced economies the recession itself is caused by a private sector investment strike. Of the €11.8bn fall in output in the two years of recession to 2010 the decline in investment (gross fixed capital formation) accounts for €9.9bn, or 84% of the total. This is not to say that households have not been badly hit, and consumption has fallen by nearly as much, €8.9bn (statistically offset by other factors such as falling import demand). But this is in response to falling incomes, rising unemployment and increasing taxes. The driving force is the investment strike- which actually began prior to the recession and now has fallen by 25.9%, compared to a decline of 6.6% in household consumption.

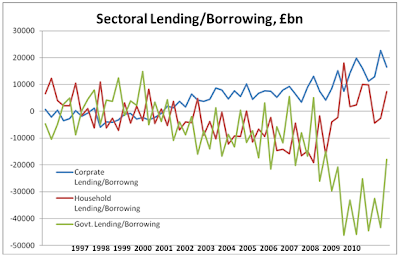

Since the financial accounts of the main sectors of the economy must balance; businesses, households and government if the former two increase their savings/reduce their consumption, then (excluding the external sector) government is obliged to decrease its own saving/increase its borrowing. As elsewhere, the cause of the increase in the public sector deficit and the recession is the same – the private sector investment strike.

But troika policy has not been focused on addressing this investment shortfall but has instead attempted to correct the public sector deficit via sequestration of the incomes of the household sector both directly (lower wage, tax increases) and indirectly (public spending cuts, reduced welfare payments). The effect has been disastrous because it attacks households’ ability to save, a necessary function in any market economy. The more ‘austerity’ that is heaped upon them the sharper the fall in household incomes, and the greater the propensity to save. Instead, a policy should be pursued which addresses the cause of the economic and fiscal crisis. This should be a policy aimed at increasing investment in the economy.

Increasing investment can be pursued in two ways, through international efforts and domestically.

On the international front, clearly the Greek government cannot borrow in the markets and under the impositions of the troika will not be allowed to borrow from them for investment. Yet the EU has traditionally recognised the need to make capital transfers to poorer regions/countries in order to bolster investment, via cohesion, structural and other Funds. These payments are still being made in Eastern Europe, and account for Poland‘s ability to escape recession entirely, for example.

The crisis-hit countries of the Euro Area have just become a lot poorer and on current policy settings will become further impoverished. The previous transfer payments were not altruism, but increased the market for goods and services produced in the ‘core’ economies. At the same time they had the intention of keeping economies together in a single currency area despite their widely different levels of productivity. They prevented repeated rounds of competitive devaluations, which also benefited the core economies.

Therefore, rather than another bailout for private creditors there should be a first bailout for the Greek economy, so that it can be invested productively and growth restored. This should be financed by the core economies, at no greater cost than their intended further bank bailout. Other countries might be willing to participate if there were reasonable investment returns on infrastructure, housing or other investment, perhaps including China.

On the domestic front, there are large resources available in the Greek economy, if only the government chose to access them. In the table below we show the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the Greek economy, a measure of output which simply excludes the effects of taxes and subsidies. These are in nominal, not real €.

|

Nominal GDP & Its Distribution € billion

|

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

|

GDP

|

236.9

|

235.0

|

230.2

|

|

Compensation of Employees

|

86.3

|

88.6

|

83.5

|

|

Gross Operating Surplus

|

124.9

|

123.7

|

121.8

|

|

Taxes on production (less subsidies)

|

29.4

|

26.7

|

28.4

|

|

Source: OECD

|

There are a number of striking features from the data. First the Gross Operating Surplus (GoS) of firms is vastly in excess of the compensation of employees (CoE), that is akin to capital and labour’s relative share of value created. On this measure the GoS is nearly 53% of all value created, compared to just 36.3% for labour, and Greece is by far the most exploitative economy in the Euro Area.

Capital’s excessively high share of income combined with an investment strike starves the economy of its lifeblood, while the excessively low compensation share also weakens its effective final demand.

Secondly, the sums are enormous. It should be recalled than the Greek deficit may amount to €24bn in 2011. Yet taxes on production amount to just €28.4bn, even while the GoS is a staggeringly high €121.8bn. Therefore taxes on production could be significantly increased as a decisive contribution to the necessary combination of deficit-reduction and investment.

A Progressive Default

There have been widespread calls for default and even for unilaterally exiting the Euro Area and reintroducing the Drachma. This last policy is in fact especially dangerous to the Greek economy and most of its population (the exception are those whose wealth can be held overseas or whose incomes derive from overseas, such as the shipping billionaires).

Any New Drachma would immediately devalue versus the Euro and thereby increase the local currency value of the existing debt. Since there is no legal mechanism for such an exit it would no doubt be declared illegal by the authorities working for the bigger powers, not just Germany and France but also Britain and the United States. Since they are already insisting on privatisation as the next chapter in the dismemberment of the Greek economy, the ‘illegal’ exit could be the pretext for the seizure of all manner of Greek assets, including public utilities and state-owned enterprises as ‘compensation’.

In addition, Greek banks have accepted deposits in Euros but their key asset would now be in devalued New Drachma so they would immediately be rendered bankrupt. Only a government prepared to protect all the deposits by taking them into public custody, and itself taking control of key assets to forestall their seizure by the foreign powers, could deal with this. Since Mr Papandreou or any likely successor in the foreseeable future is not Fidel Castro, then that is unlikely to happen. Instead, it is Germany, France, Britain and the US who would be in a position to seize assets. Advocating unilaterally leaving the Euro would unleash just such a dynamic.

As already stated, the question of default seems unavoidable. But efforts should be made to avoid a ‘disorderly default’ which would lead to the same consequences as unilaterally exiting the Euro. It is this type of default being promoted now by Cameron, Osborne, Boris Johnson and others and coincides with the interests of British banks who have exited the Greek government bond market and who feel that they can at least gain a relative advantage from competitors’ distress, or may even have a position to profit from a default.

It is possible if, for example, that the ECB retaliates to a default by withdrawing its liquidity provisions to the Greek banks or by refusing once more to accept Greek government bonds as collateral for liquidity provided to other Euro Area banks. This would bankrupt Geek banks, freeze Greece out of international markets for a prolonged period, and require the immediate closing of the deficit. Unless most of the public sector was fired and welfare payments abandoned, the only way to avoid that would oblige the government to introduce a new currency, or quasi-currency.

Comparisons with the Argentinan and Russian defaults are invalid for that reason. These countries had only debt obligations to countries such as the US. Greece, a far smaller economy than either, has Treaty obligations too which can be used against it.

Instead, a programme of investment-led deficit reduction, financed by core economies and Greece’s own resources would address the objective requirements of the economy. Under those circumstances, it would make no sense to continue further payments to private creditors, so default (or ‘restructuring’) is required. In addition, the accumulated debt burden is unsustainable, so all existing holders of Greek government debt would be obliged to take significant losses. If the Maastricht Treaty insists that 60% is the maximum permissible debt/GDP ratio then it can be asserted that the ‘haircut’ imposed on holders of Greek government debt (which stands at 154% of GDP) must be no less than 61 cents in the Euro, preferably more, for prudence sake.

T Walkerhttps://www.blogger.com/profile/11107827543023820698noreply@blogger.com1

Recent Comments