Is Ireland experiencing a boom?By Michael Burke

The economy in the Republic of Ireland expanded by 1.5% in the 2nd quarter and by 6.5% from the same period in 2013. This leaves the economy well below its previous level but is actually much stronger than the annual growth rates in the same period in Britain’s ‘boom’, of 0.9% and 3.2%.

For a number of decades the Irish economy has grown more rapidly than the British economy and per capita GDP is higher in the Irish Republic. According to the OECD this is true if constant prices and Purchasing Power Parities are used, or whether current levels are used for both.

This relative outperformance is likely to continue in the future. This is because the Irish economy is more thoroughly integrated into the world economy (or, put in classic terms, it has a higher participation in the international division of labour). This is true even taking into account the effect of multi-national corporations booking profits in Ireland based on production that takes place elsewhere.

The British economy too has its own mechanisms for facilitating international tax avoidance, including the network of overseas territories Guernsey, Jersey, Gibraltar, BVI and so on.

Once this ‘soufflé effect’ is removed it is clear that the export of goods from Ireland is a vastly greater proportion of GDP than are British exports. This, combined with the tendency for an increase in the international division of labour, which is expressed as the faster growth of world trade than domestic GDP, means that the Irish economy is set to grow faster than Britain over the longer term.

But faster growth than Britain is a poor yard-stick. It is utterly foolish of British supporters of austerity to gloat over the relatively better performance of the British economy than the French economy. Declining prosperity elsewhere does not constitute economic well-being here.

Similarly, the focus should be on what is the maximum sustainable growth rate for the Irish economy and the mechanisms to achieve that. In light of the Irish economy’s degree of integration into the world economy, the current rebound in Irish GDP falls well short of what is possible or desirable.

A version of the article below first appeared on Irish Left Review under the title Investment Remains the Key to a Real Recovery.

===============================================================

The Irish recession which began in the final quarter of 2007 is the most severe in the history of the state. GDP contracted by 12.1% in a little over two years ending in the 4th quarter of 2009. That slump is not over. The latest data for second quarter of 2014 show that the economy still remains 3.4% below its pre-recession peak. In effect it is likely to take 5 years or more simply to recover the output that was lost in in the slump.

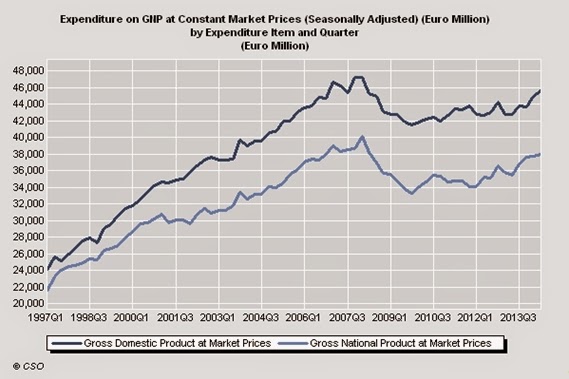

Even then, the economy will remain way below its previous trend rate of growth. This is illustrated in Fig 1 below, which shows real GDP and real GNP from 1997 to the present. The average annual growth rate of the Irish economy from 1997 to 2007 was approximately 6%. Maintaining the trend rate of growth would have led the economy to be approximately 50% larger than it is currently, and there is a danger that this potential is lost permanently.

The causes of the slump are very clear. Over the entire period of the crisis the fall in investment more than accounts for the entirety of the decline in aggregate measures of output, either GDP or GNP. GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2014 is still €6.6bn below its late 2007 peak. Investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, GFCF) is €14.4bn below its peak. There are other components of GDP which have also failed to recover, notably personal consumption and government expenditure. But even taken together, their combined fall of €10.1bn is less than the fall in investment. The only component of GDP which has risen is net exports. The change in components of GDP is shown in Fig.2 below.

This data belies the notion that there is an ‘export-led recovery’ under way. Recorded net exports have grown very strongly, up €30.5bn over the period. But only one quarter of this or €7.4bn is a rise in the export of goods. A much larger statistical contribution has arisen from the decline in the imports of goods, down €14.6bn. As both investment and consumption have fallen, this simply suggests that both firms and households have been priced out of world markets by reduced purchasing power. The remainder of the rise in net exports is derived from international trade in services. These are particularly prone to the tax-induced flow of funds that plague the Irish economy and completely distort the economic data. There is little benefit from attempting to unravel them.

More importantly, it is clear that exports have not led a broad-based recovery at all. All the main domestic indicators of activity, consumption, government spending and investment are still far below their pre-recession peaks.

The recovery

The low-point for the Irish economy was reached in the 4th quarter of 2009. There is not yet a recovery. But there is a rebound from that low-point, which has not always made smooth progress. Every year since 2009 has seen at least one quarter of economic contraction. It is hoped that 2014 will be different.

One reason for this volatility in the data is the activity of multinational corporations. For example one large order for aircraft, none of which are produced in Ireland but are booked in this jurisdiction, can provide a large one-off boost to GFCF and to GDP.

The engine of the recovery is also clear if we take the inflection point from the 4th quarter of 2009 to the most recent data. This is shown in Fig.3 below.

The rebound in both GDP and GNP since the end-2009 low-point is driven solely by the rise in net exports. Of the €24bn rise in net exports over that period just €8bn is a rise in the net export of goods.

Otherwise there has been no improvement in the other components of GDP even during this phase. Personal consumption and government expenditures have fall by a combined €2bn. Again, this is exceed by the fall in investment, down €2.7bn since the end of 2009.

The motor force of the Irish economic slump has been the fall in fixed investment. Ireland’s openness to the world economy (its high degree of participation in the international division of labour) provides a real benefit to the economy, even if that is vastly overstated in the official data.

But for exports to lead the economy investment must grow. Otherwise Irish goods (and genuine services) become priced out of world markets. The investment strike in Ireland has not ended. Until it does there can be no confidence in the sustainability of any eventual recovery.

Recent Comments