By Tom O’Donnell

This government talks about growth, as Jeremy Hunt recently did, but will only deliver further stagnation and renewed attacks on the living standards of the majority. Any plan for sustainable growth and prosperity must include a radical break from current policies. Yet there is no sign that this Labour leadership is prepared to deliver that.

The 2023 forecasts for the British economy are grim. The latest IMF forecasts have received significant attention, with ministers attempting to rubbish the Fund’s forecasting track record. It is quite true that the IMF’s forecasts are patchy at best. But it actually has an inherent bias towards the US economic model and regularly overstates US GDP growth relative to outcomes. As Britain is the nearest European follower of that US, a smaller upward bias is also evident in its British forecasts too.

The IMF forecasts that the British economy will barely grow at all in 2023 and 2024, and that its performance will be much worse even than Russia’s. Over the medium-term, out to 2027 the IMF expects average growth in the British economy to be less than 1.4% annually.

But ministers should be aware that this gloomy outlook for the British economy is shared by private sector forecasters. Goldman Sachs is one of the latest to weigh in, arguing that a contraction of 1.2% in real GDP this year will be the worst in G10 group of countries, and that it will be followed by a rebound of just 0.9% in 2024. This is only marginally better than their forecasts for Russia, which is at war and suffering under Western sanctions.

The Hunt response to such an abject crisis is pathetically weak, with calls for more optimism and rehearsing tired arguments about British innovation and the need for low taxes. There is no evidence that high corporate taxes depress growth, and the claims on British innovation are hyperbole. The British economy is 7th in the world in new patents filed, which are the intellectual property claims on innovations. This is just ahead of Switzerland, less than one third of the German total, and less than one-twelfth of China’s world-leading total.

In essence, Hunt’s prescription is to try everything to spur growth except what is known to work. Boosterism, unsubstantiated claims and special pleading for business are fantasy economics and will not work. In fact, even Hunt does not seem to believe in them, arguing that he has a ‘framework for growth, not a growth plan’. He has neither.

Only Investment in the means of production allows a sustainable increase in production of goods and services. These are what are required in order to achieve any sustained rise in either growth or prosperity.

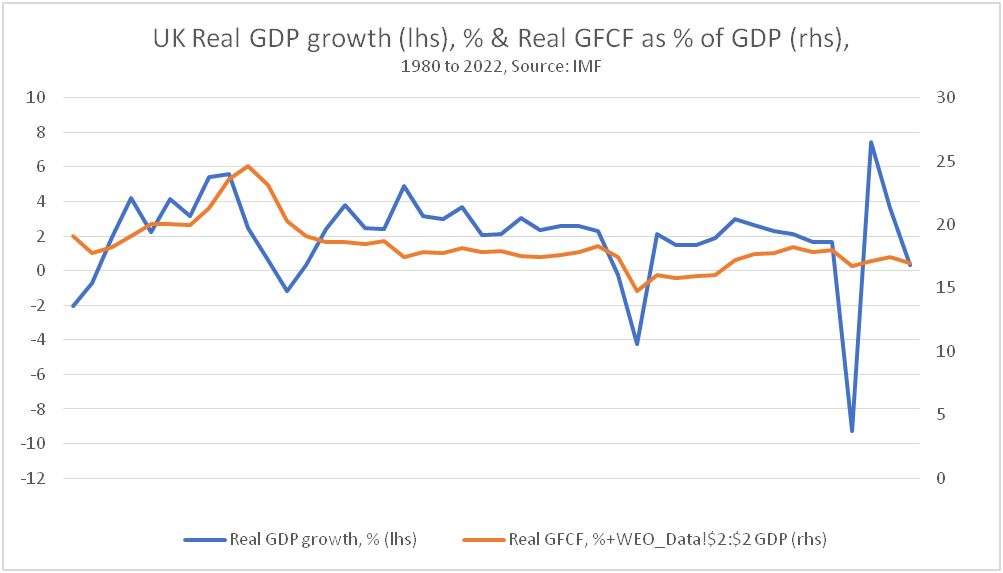

The decline in the British economy over several decades has been driven by a decline in the rate of Investment in Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF). To take an obvious contrast, in the 5 years to 1990 GFCF averaged 23.4% of GDP each year and real GDP growth averaged 3.5%. The equivalent data for the latest 5 years, including IMF projections for 2023 is GFCF at 17.25% of GDP and real GDP growth of 0.75% annually.

Investment is decisive. But successive governments over decades have refused to engage in the large-scale public sector Investment that would spur growth and induce the private sector to investment at a greater rate, or a least prevent the decline in Investment that has taken place.

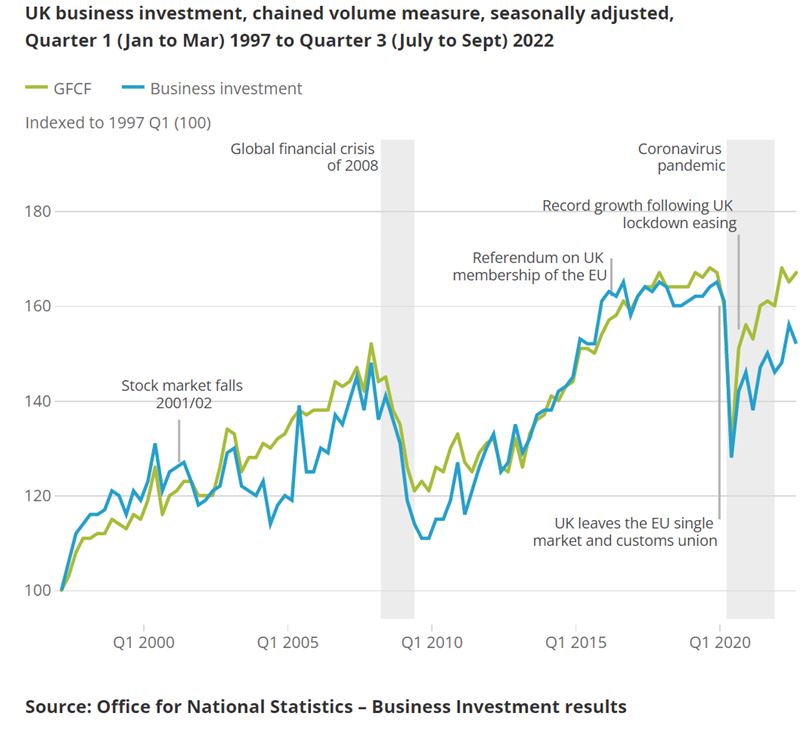

Within that total, the main factor is the weakness of business Investment, which has never properly recovered from the Global Financial Crash in 2007 and 2008. Business Investment was £52.4 billion in 3rd quarter 2022, compared to £50.9 billion in 4th quarter 2007. The economy is on course for a lost generation of Investment, because of a business investment strike by firms based in this country.

However, the absence of a Hunt growth plan (or even the correct framework) does not mean that there is no economic policy. That policy is played out daily in the street and on the news programmes. The government’s plan is drive down wages, increase the rate of exploitation and thereby hope to increase the rate of profit. This is true across the whole economy.

This begins with the mantra that they need to oppose a ‘wage-price spiral’. Nonsense that wage rises cause inflation was completely refuted by Marx 150 years ago, in Value, Price and Profit. Marx argued that there was nothing fixed about either the value of production, or wages, or the relationship between the two. In effect, the level of wages and the level of prices (or the level of real wages, which is the same thing) is set by the class struggle between two major classes and in all its forms.

The blatant hypocrisy of this campaign, which is not gaining traction in the public, is highlighted by a recent report that shareholders’ dividends are rising by 16.5% a year to £84.8bn. Of course, this is a far faster than wages which are falling in real terms. It is also a refutation that wages are driving prices higher (where you would then expect to see falling dividends). It shows the fruits of the efforts of the drive to lower real wages, increased exploitation and boosted profits.

In the drive to lower real pay the government can directly determine the rate of public sector pay. It is clearly also trying to determine the settlements in large parts of the economy which were formerly in the public sector, such as post and the railways. The aim is twofold. First is to drive down pay across the economy as a whole, using the public sector to ‘set the going rate’ for below-inflation wage settlements. Secondly, it is redirect as much of the total social product from labour to capital as possible, in effect driving down real pay and using the savings to fund cuts to corporate taxes.

To this is added draconian legislation in the right to strike, to picket, to assembly and to vote. This is an all-round offensive on the working class and its allies, to curb their economic and political power. It is a fight the government is determined to win, as the ruling class has no other plan to arrest its own decline.

Yet, just as there no crisis that cannot be resolved by loading the burden of it onto the backs of workers and the poor, so too there is no crisis of living standards for workers and the poor that cannot be alleviated (at least temporarily) by making capital pay for the crisis.

So, this is the question posed for the next government, which increasingly looks like it may be a Labour-led one. It was essentially the same question that was posed for the Corbyn-led Labour party in 2017 and 2019.

The question is not, How do we introduce socialism? Socialism requires first the seizure of state power by the working class. This is not on the agenda in Britain in any foreseeable future. Instead, the pertinent question is, What policies are required to reverse the attacks on the living standards of the majority, and to sustain that increase in prosperity?

Some combination of redistribution and Investment-led growth is required to achieve that. That must be the starting-point of any serious discussion on the left on economic policy over the next period. Otherwise the danger lies in reworking the garbage coming from Hunt and others, who have no intention of improving the living standards of the majority.

Recent Comments