.525ZBribing the private sector to invest isn’t workingBy Michael Burke

The government’s flagship scheme for promoting investment in infrastructure has been branded a failure. A report in The Times[i] quotes speakers for both the Engineering Employers Federation and the Confederation of British Industry as saying that the scheme is ‘disappointing’ and ‘more needs to be done’.

In July 2012 the government announced the scheme, saying that it would use its balance sheet to support infrastructure investment as the means to revive the economy. Bond holders are willing to lend money to the government but less willing to lend to private capitalists. The government’s scheme was supposed to use this advantage to offer guarantees to the private sector so that they would invest in infrastructure projects. These are increasingly and correctly regarded as a key mechanism to boost growth and employment and to address the British economy’s creaking infrastructure.

However, it is reported that only one project has been agreed, the extension to the Northern Line tube in London, which would have gone ahead without the UK Guarantee.

The government’s inability to promote private infrastructure spending occurs as its own investment continues to be cut. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, government investment will be cut by nearly 30% in total under current government plans. These may alter in the next Budget in March.

Investment driven by profits

The failure of the government’s policy to deliver any new infrastructure spending is because of an insistence on the failed neoliberal model of the economy. One of the many central and incorrect tenets of neoliberalism is that all ‘economic agents’ are essentially the same. Those economic agents are private firms which maximise revenues and private individuals who maximise their own well-being. Form this is it is argued that government stands in the way of this series of rational choices, by taxing and spending incomes that firms and individuals could better choose how to spend themselves.

This is a concocted world which bears little relationship to reality. Neither firms nor individuals operate in a world of perfect knowledge to inform their expenditure, economies of scale often mean that government can purchase the same goods or services in bulk much cheaper (education, health, transport, banking, etc.) than private firms or individuals can. For large infrastructure projects it is often the case that only government can borrow funds sufficiently cheaply for large-scale investment.

But perhaps the biggest fallacy of all in the neoliberal model is the one in the sphere where it claims the greatest authority, which is the factors governing the behaviour of private firms. Firms don’t seek to maximise revenue at all, as the neoliberals claim. They seek to maximise capital, which normally means to maximise profits. And they don’t face a multitude of competitors each seeking to compete by allocating investment more productively than the next. In the most decisive areas of the economy, banking, cars, aviation, large scale housing, energy production, and so on there are just a handful of firms. They are oligopolies. This means that frequently the way to maximise profits is to increase prices, sometimes reducing supply to do so.

The housing crisis

To take just one example, there is a structural shortage of at least 2 million homes in England and Wales alone, comprised of the numbers of households on waiting lists for housing (1.7 million) and others in grossly substandard accommodation. Yet there were just over 100,000 new homes built in the latest 12 month period. This is slightly less than the growth in the number of households, meaning that the housing shortage is increasing.

Yet the Financial Times recently reports that UK housebuilders are enjoying a ‘state-backed boom’[ii]. The boom is in the share price of the stock market-listed housebuilding firms, up 46% in the last 6 months, based on an unprecedented rise in profits.

These profits arise because the term ‘housebuilder’ is a misnomer. Housing starts are at record lows but, Barratt (one of the biggest firms) has been buying land at its fastest rate ever. These firms are in reality land buyers, who have an incentive in hoarding land, which continues to rise in price and in restricting the supply of new housing for the same reason. According to Noble Francis, economics director and the Construction Products Association, ‘The major housebuilders are not going to double the number of units they build because it’s not in their interest’.

Government subsidies for mortgages simply operate as a price-support mechanism for the housebuilders. This is a ‘state-backed boom’ for capitalists, not for house building.

Dividends versus investment

Just as the large housebuilders have no interest in increasing the number of houses they build as they seek to maximise profits, not revenues, so capitalist firms in general have no incentive to produce without the expectation of profits. Not all firms are as fortunate as the housbuilders to be oligopolistic suppliers to a market where there is already a structural shortage. As a result, the profits of most firms have not risen in the same way.

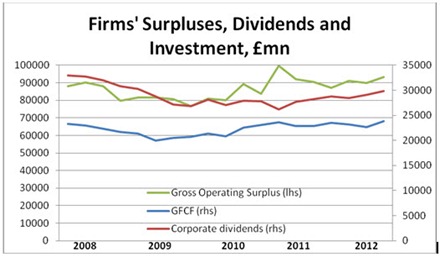

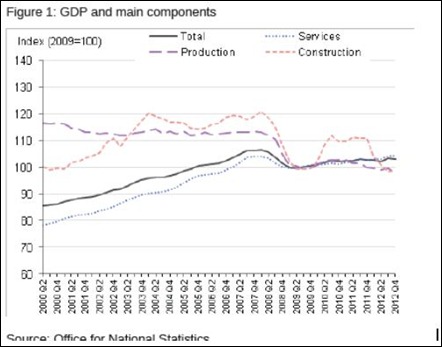

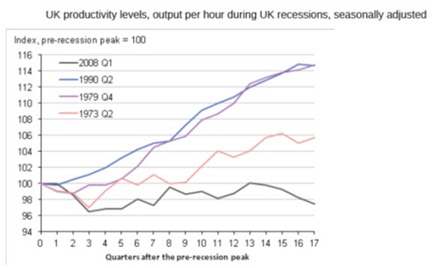

The chart below shows the gross operating surplus of firms (green line, left-hand scale). The gross operating surplus is often described as the profit share of national income and is similar to the Marxist category of surplus value. The chart also shows the level of investment by firms (gross fixed capital formation, blue line right-hand scale) and the level of dividend payments to shareholders (red line, right-hand scale). Together, these two form the overwhelming bulk of the distribution of the surplus. The other main category is interest payments, which have fallen sharply as both interest rates and debt levels have fallen.

Chart 1

In effect, firms can either invest profits or distribute to them in the form of dividends to shareholders. Nominal profits have only just recovered, to £68.2bn in the 3rd quarter of 2012 from £66.6bn in the 1st quarter of 2008. But investment has fallen to £29.8bn, from £33bn. At the same time corporate dividends have increased sharply, from £21.5bn to £25bn.

If we compare the respective low-points for the gross operating surplus, investment and dividends the picture is even more stark. On this measure, the surplus has increased by £11.1bn from its recessionary trough, but investment has increased by just £3.6bn. The bulk of the surplus has gone to shareholders, with dividends increasing by £7.4bn.

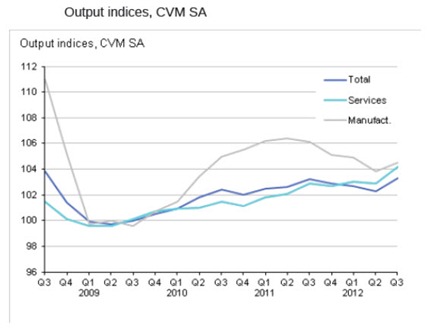

Chart 2

Because the increase in the profit share has been minimal, the willingness of firms to invest has been minimal. The purpose of capitalism is to maximise capital which requires generating profits. In the chart above the official measure of the profit rate is shown. Although this official measure from the Office of National Statistics has some shortcomings, these do not invalidate the overall trend described in the data. This shows that the profit rate has recovered from its lows, but is very far from a full recovery. This meagre increase in both the profit share and the profit rate explains the unwillingness of capitalist firms to invest.

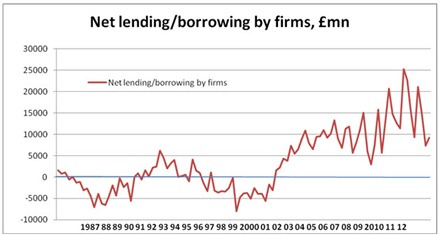

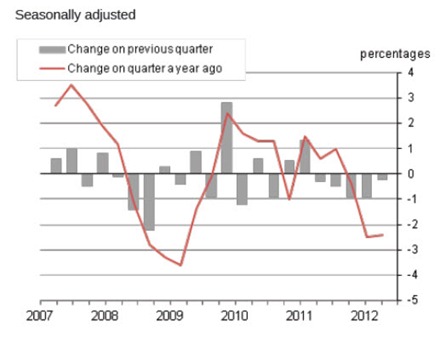

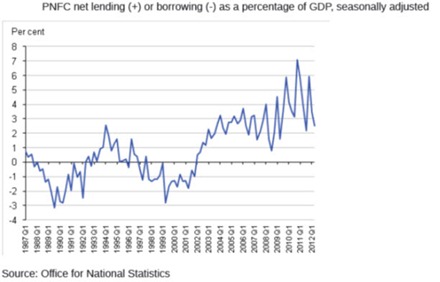

However, unwillingness to invest is not the same as inability. British firms’ refusal to invest and increased payouts to shareholders have also been accompanied by an increase in their net savings as shown in the chart below. In a vigorous capitalist economy where firms borrow to invest. It is a measure of the decrepit nature of British capitalism that over the 25 years, borrowing has been unusual, and corporate savings have been the norm.

Chart 3

As a result of this prolonged bout of savings, the cash balances of British non-financial firms have reached record proportions. At the end of December 2012 there were £777bn in sterling short-term deposits held in UK banks, not including deposits by other banks or public sector bodies. The bulk of these are deposits by firms who are simply hoarding cash.

It is frequently argued that nothing can be done with this cash pile, as it belongs to the private sector. But we are also told the George Osborne has directed that RBS pay its LIBOR scandal-related fines from bonuses. This is simply because a further round of bank bonuses would be massively unpopular.

It is therefore absolutely clear that the government’s 83% stake in RBS means that it can direct bank policy if it chooses. Instead of failed bribes to the private sector to invest, the government could simply direct RBS to lend the funds to the necessary infrastructure projects required to boost growth and jobs. It could lend to local authorities to build council houses and so on. Given that every bank operating in Britain can only do so with the support of a government guarantee for deposits, liquidity support from the Bank of England and other measures. If the government insisted, they would all have to increase lending.

The state can do this because unlike the private sector, it can invest without the requirement to generate profits for shareholders. The policy of bribing the private sector to invest has already failed.

[i] ‘Scheme is no guarantee of reviving the economy’, The Times (£), February 4,

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/business/economics/article3676984.ece[ii] ‘Housebuilders enjoy state-backed boom’, Financial Times (£), January 22,

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/38a7e488-64ab-11e2-934b-00144feab49a.html#axzz2K8MyzDaq

Recent Comments