.790ZThe alternative to the EU Single Market is TrumpBy Tom O’Leary

Once Britain leaves the EU Single Market the sole realistic alternative will be to do a trade deal with Trump. This will be far worse than the current Single Market and will also be far worse than the TTIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) which was formulated under Obama.

The limits on trade are ultimately set by the extent of the world market. Although world trade grows over time and tends to grow more rapidly than world output, the scope for trade is itself limited by the size of the world market. Like any country, the UK cannot trade with Mars, or imaginary countries or under imaginary conditions. It can only trade within the boundaries of the world economy. If the UK leaves the EU Single Market it really only has one other option to partially replace the trade that will be lost. The real choice is not between the Single Market and ‘prosperity on the open seas’ as many Brexit supporters seem to believe. The actual choice is between the EU Single Market and Trump’s America.

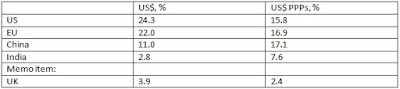

The reason the choice is so stark is purely factual. The world has three continental-sized economies, the EU, the US and China. In strictly cash terms they together account for 61% of the world economy. It is not possible to maximise the prosperity of any economy by focusing on the remainder of the world economy. The next largest economy in cash terms is Japan, which accounts for less than 6% of world GDP, and this share is declining.

If Purchasing Power Parities (PPPs, which adjust for distortions created by exchange rates) are used, the EU, US and China still account for half the world economy, 49.8% of GDP using World Bank data. The next largest economy behind these three is India, and is half their size in PPP terms. Table 1 below shows the relative size of the world’s leading economies, and includes the UK economy for reference.

2015 Country Share of World GDP

Source: World Bank

‘Free trade’

The pursuit of ‘free trade’ deals is a mirage. Currently, the world economy does not operate a free trade system. It is not feasible that it will in the near future, although fundamental forces push in that direction over the longer run. Instead, countries operate behind a system of tariff barriers on goods and services and impose restrictions (non-tariff barriers) on goods and services. Almost all ‘free trade agreements’ are in reality agreements to reduce these tariffs and barriers, not to eliminate them.

This is not the same within economies, which generally operate with far fewer barriers and tariffs. This is true within the US economy, as well as China and the EU, as each of them operate their own ‘single market’ (as does the UK). It is this closer approximation to free trade that the UK is leaving.

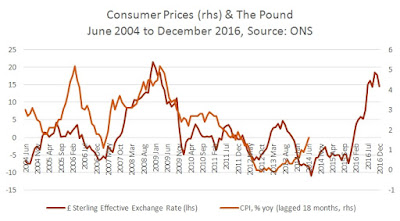

It is not possible to construct a single significant trade deal which would allow the same level of unfettered or relatively free trade as currently exists within the EU Single Market. This is especially true given that the parties to a trade agreement operate different currencies. Trade and other barriers remain in place in part to offset the possibility of a sharp currency devaluation by one side, which undermines the competitive position of the other.

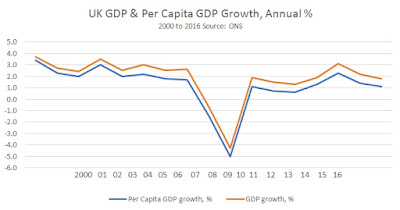

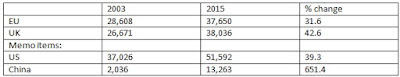

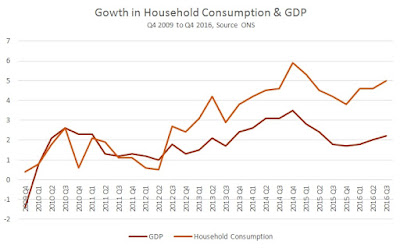

Most single markets operate with one main currency. The UK had a highly unusual and privileged position within the EU in being allowed to have freedom for the currency to fluctuate while being in the EU Single Market. Partly as a result of this freedom, the UK has actually been a greater beneficiary since the creation of the Single Market than the rest of the EU (as shown in Chart 1 below).

Chart 1 UK, EU Per Capita GDP (US$, PPPs)

Table 2 below shows the UK and EU per capita GDP from 2003 to 2015. For comparison the US and China are also shown. The UK performed significantly better than the EU and marginally better than the US on this measure, although of course they all performed much worse than China.

Table 2 Per capita GDP (US$ PPPs), 2003 and 2015

Source: World Bank

Relative strength

It is also completely impossible to construct a series of trade arrangements which allow the degree of free trade equivalent to the free movement of goods, capital, firms and labour in the EU. This is because each country’s trade priorities and interests are different. Every trade deal done affects other potential trade deal.

So, where the US might insist on free trade in most agricultural goods which would devastate farming in this country, India would insist on protecting its farmers from British and American competition. India would therefore be unable to conclude a UK trade deal including agriculture and the British approach would to be to limit freer trade in another sector reciprocally. In fact concluding any serious trade deal with India or other countries will be difficult unless the UK changes its attitude to immigration. Theresa May returned from her much-vaunted trade trip to India with virtually nothing, as she refused to allow more Indian immigration, business and student visas.

Therefore, the deal that will be struck with Trump will be decisive. It will also reflect the relative economic interests of the US and the UK. It will not reflect any ideological commitment to free trade. It is clear that Trump has no such commitment.

The terms of negotiations between the UK and US will reflect the real relationship of forces between the two economies. The US economy is approximately 6.5 times greater than the UK economy. But this is not the sole measure of the UK’s relative weakness. There are only two economies in the world larger than the US, which are China and the EU. The UK is leaving the EU and is prevented from allying with China in trade and investment terms because it is hamstrung by its own backward ideology. It has only one choice when the EU is rejected.

By contrast, for the Trump negotiators, there are ten economies in the world whose GDP is greater than or more or less equal to that of the UK (on a PPP basis). It will be the UK which is desperate for a deal, not Trump.

Dealing with Trump

Trump is not a neo-liberal, but a protectionist. He does not favour tearing down all protective walls and barriers in the manner of the ‘Washington Consensus’, which has dominated official policy making for more than 35 years. Trump has issued a series of threats regarding new US tariffs and has suggested that China, Germany and Japan be declared ‘currency manipulators’. Under US law this would allow the imposition of trade tariffs and sanctions on the targeted countries.

This list is not accidental. The three countries have the largest external surpluses (current account surpluses) in the world, while the US is the world’s largest deficit country in cash terms. The US requires capital inflows to fund its deficit and these are the countries which can provide those flows from their own resources. If, as seems likely, Trump will cut taxes for business and the rich and may also increase spending on the military then the external deficits will widen and US dependence on those inflows will only increase.

Germany is a long-standing ally of the US. Japan is too and actually adopts a wholly subservient role to the US. Japanese Prime Minister Abe caused embarrassment and outrage at home when he suggested Japanese investment could create 700,000 US jobs even while Japan itself is stagnating. Japan outdoes the obsequiousness even of the UK’s ‘special relationship’.

Yet Germany and Japan get the same initial treatment as China, who members of the Trump Administration openly describe as an enemy. The UK should also therefore expect the tactics of bullying and threats to be deployed in promoting US economic interests in any trade deal. There is already one trade deal crafted, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). But, despite the acceptance of US negligible environmental and consumer standards, and the legally privileged role for multi-national companies, and the inevitable assault on public services like the NHS, Trump has binned the TTIP because it did not promote US business interests sufficiently. Trump does not do ‘quid pro quo’. There are only winners and losers in his deals, and it is absolute certain that the UK will not be the winner. Any deal eventually struck will be worse than TTIP.

Will it work?

Because something is objectionable it does not mean it cannot happen, or that it cannot endure for a period. The question must be posed, would a trade deal with Trump work? Would a central trade deal with the US supplemented by less comprehensive deals with other countries compensate for the lost trade with the EU?

Of course, it is impossible to know now the precise level of tariffs and non-tariff barriers that will be imposed on the UK outside the Single Market, although if Theresa May’s Hard Brexit is not opposed the terms are likely to be very onerous. But the sheer volume of the respective UK trade ties to the EU and to the US make it impossible that increased trade with the latter could off-set a significant decline in the former. The total volume of UK-EU trade in goods and services in 2016 was £385 billion. The equivalent volume for UK-US trade was £84 billion. These proportions mean that even a small proportionate fall in EU trade would require a significant rise in US trade volumes simply to stand still.

Here it is important to point out an important fallacy which focuses on trade balances rather than trade volumes. It is an error made by Trump himself, but unfortunately is widely echoed in broader economic commentary, and lends his bombast credence. Trump argues that US industry is being ‘killed’ by cheap Mexican labour and cites in evidence the wide trade gap with Mexico since the introduction of the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

NAFTA was introduced in 1994. Since that time the level of US exports to Mexico have increased by 413%. Imports have grown by 591% and the US trade balance has switched from a $5 billion surplus to $58 billion deficit. In the Keynesian system of GDP accounting net exports are now a negative. But the idea that the increase in exports to Mexico, and the jobs that depend on them makes the US worse off is ludicrous. The US is a significant beneficiary from NAFTA in much higher exports as well as much cheaper imports.

In reality the generalised trade deficits of the US, like the UK, arise because it is uncompetitive. The US is uncompetitive because it invests too little to sustain both the prevailing level of the currency’s exchange rate and trade balances or surpluses. It runs trade deficits with virtually every other country on the planet, including countries where wages are higher, such as Germany. One measure of the US lack of competitiveness is that the US even runs a trade deficit with the UK, and is the only large economy to do so. Only a sharp increase in the rate of investment, probably combined with a large currency devaluation could reduce the chronic US trade deficits. Trump may consider the latter at least, but a falling US Dollar would undermine efforts to get overseas investors to increase their funding of growing US deficits.

Conclusion

The only realistic alternative to membership of the Single Market is for the UK to do a trade deal with the US. Trump’s version of ‘making America great again’ is to make other countries worse off. The UK will be obliged to take whatever deal is offered, which is likely to be worse than the TTIP. Any new deal is unlikely to compensate for the lost trade with the EU and will come at a significant price, in terms of workers’ rights, environmental protections, consumer safeguards and the privatisation of UK public services. This will all be a direct consequence of Brexit.

Recent Comments