By John Ross

Introduction – the situation in the global economy since 2008

China is used, after repeated experiences, to the ‘China is in/about to enter a deep crisis/hard landing’ genre in sections of the Western media.(1) The picture presented in such claims is that in contrast to a ‘stagnant’ China the West, in particular the US, is showing economic dynamism driven by a wave of innovation. This situation allegedly interrelates with China’s domestic trends. Such analysis is repeated in parts of the Chinese media by what might be referred to as China’s ‘comprador intelligentsia’. These analyses, for reasons that will become speedily apparent below, are invariably characterised by lack of any systematic factual analysis.

Regular accurate refutations of such claims appear in China’s media and therefore the aim of the present article is rather different. It goes beyond individual cases to examine systematically the fundamental situation of the Western economies. The results show clearly why the anti-China material referred to above lacks any systematic factual analysis of the global economy – because such examination shows that their claims are the precise opposite of the facts. Far from ‘dynamism’, the fundamental reality of the West today is very slow economic growth, the extremely striking character of which becomes apparent by comparing it to previous economic periods in the global economy during the last century. The factual reality is that the Western economies are in the midst of what is best described historically as a ‘Great Stagnation’ – to be precise it will be shown that in the present overall period, commencing with the international financial crisis, the growth rate of the Western economies is actually slower than in the ‘Great Depression’ after 1929. The data used to establish this does not come from any Chinese or peripheral sources but from the bastion of international economic orthodoxy – the latest report on the global economy by the IMF.

To avoid any misanalysis it is shown below that of course the violence of the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 was much greater than after the international financial crisis in 2008. The feature of the present period is of a prolonged phase of slow growth, rather than of a violent recession followed by relatively rapid growth as occurred in most major economies after 1929. Nevertheless, this does not alter the reality that the present period as a whole is actually seeing slower average Western economic growth than during the Great Depression. This economic trend also means that whereas the political crisis after 1929 was rapid and violent the development of the crisis after 2008 is much slower and cumulative.

Clearly establishing this real factual situation of slow growth in the Western economies, however, does not only cast light on short term processes. It creates an integrated framework for understanding the relation of the current period in China with international trends. In particular:

- This relative stagnation of the Western economies explains the interconnection between underlying economic trends and immediate events such as US actions in Syria, US policy to North Korea, major Western political events such as Trump’s election and Brexit, China’s current economic situation, and strategic developments such as One Belt One Road (OBOR), etc.

- Key new initiatives in China’s policy launched by Xi Jinping are coherently interrelated with the objective changes in the global economy since 2008.

- The international financial crisis of 2008 inaugurated a new period of the global economy, and therefore of China’s interrelation with it, compared to the preceding ones since the creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It will be demonstrated that this response is an integrated response to the new period of the global economy since the international financial crisis. A brief analysis of some of the key consequences for countries outside China, and their interrelation with China’s foreign policy, will be given.

- It should be made clear that in this article only some international features of China’s policies are analysed – other domestic ones, such as the struggle against corruption are equally important but beyond this article’s scope, while some are domestic Chinese matters it is inappropriate for a non-Chinese citizen to comment on. But, despite this limitation, it is hoped an international analysis focusing on the new period in the world economy, as it interrelates with China, throws some light on developments both in China and internationally.

IMF data indicates predicts West’s economic stagnation will be worse than the Great Depression

To establish the fundamental features of the present period of the world economy, and given that the post-1929 Great Depression is generally regarded as the worst crisis in the history of the advanced ‘Western’ economies, a careful comparison of the similarities and differences of trends since the international financial crisis of 2008 with post-1929 developments will help produce clarity.(2) It will be shown that a statement sometimes made in the Chinese media that the period commencing with the international financial crisis of 2008 is the West’s ‘worst economic crisis since the Great Depression’ is somewhat misleading put in that form as in one crucial way it understates the problem. It will be demonstrated that the overall slow growth and stagnation in the Western economies is already almost equivalent to that after 1929 while the factual projections for the next five years lead to the conclusion that the cumulative slow growth/stagnation of the Western economies will be worse, although different in form, from that during the following 1929. Such extremely slow growth of the Western economies since the crisis of 2008 clearly has profound effects on the entire international situation and therefore analysing it casts a clear light on current trends facing China. The practical conclusions following from this are analysed below.

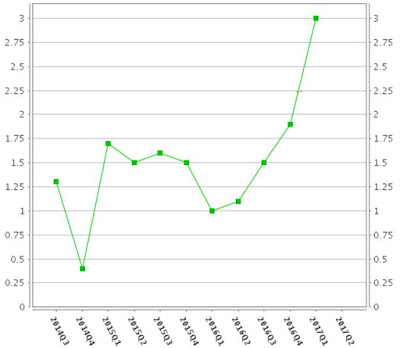

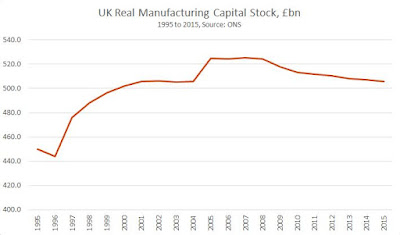

First, however, the key facts must be established. To do this Figure 1 illustrates three sets of data:

- Growth trends in the advanced Western economies after 1929.

- The factual trend in the advanced Western economies from 2007-2016;

- The latest IMF predictions for 2016-2021

In this section the factual data will be focussed on – IMF projections will be analysed below.

The ‘Great Depression’ compared with the ‘Great Stagnation’

Figure 1 confirms the well-known fact that the onset of the ‘Great Depression’ after 1929 was much more violent than what will be referred to as the ‘Great Stagnation’ which commenced with the 2008 international financial crisis. After 1929, during only three years, overall GDP of the advanced economies plunged by 16%. Taking the dominant capitalist economies, and measuring from 1929 until the bottom of the economic decline in each country, US GDP fell by 29% in 1929-33, German GDP fell 16% in 1929-32, UK GDP fell 6% in 1929-31, and Japan’s GDP fell 7% in 1929-30 – overall West European GDP fell 9% in 1929-32.

Figure 1

As is equally well known the very rapid post-1929 economic collapse created immediate political crisis:

- In September 1931 Japan invaded Manchuria, beginning its military attack on China.

- In September 1931 Britain abandoned the gold standard, resulting in collapse of the then existing international financial system.

- In November 1932 Roosevelt was elected US President, leading to the ‘New Deal’.

- In January 1933 Hitler became German Chancellor.

But alongside these well-known and accurate facts it is not so widely understood that after the initial post-1929 economic collapse recovery during the 1930s was rapid and post-crisis growth was strong – the US being the most important exception. This can be clearly seen in Figure 1 and by examining the situation in 1938, the last year before World War II. By a convenient statistical coincidence, 1938 was nine years after 1929, and 2016, the most recent year for current factual data, was nine years after the last pre-international financial crisis year of 2007. Therefore, in comparing 1929-38 with 2007-16 the same length of time is being analysed. This makes historical comparison particularly easy – and clarifies why the present period is most clearly thought of as a ‘Great Stagnation’.

The strong recovery of most advanced economies following the post-1929 recession is demonstrated by the fact that by 1938 the GDP of most major advanced economic centres was substantially above 1929 levels. To be precise by 1938:

- Japan’s GDP was 37% above its 1929 level;

- Germany’s GDP was 31% above its 1929 level;

- UK GDP was 18% above its 1929 level;

- Western Europe’s GDP was 13% above its 1929 level;

- The GDP of the advanced economies as a whole was 7% above its 1929 level.

The US was an exception – US GDP in 1938 was still 5% below its 1929 level.

Therefore as Figure 1 shows the ‘Great Depression’ in the advanced economies was in reality a very steep ‘V’ shaped economic development – with the rising leg of the ‘V’ significantly higher than the falling one. Economic activity fell extremely sharply after 1929 and then rose sharply – the US being the chief exception.

The term ‘Great Depression’ is therefore, with the exception of the US, slightly misleading – its use reflects the dominance of analysis of the US in studies of the period rather than examination of the trends in the majority of advanced economies. After 1929, most advanced economies experienced first an extremely rapid fall in output followed by a strong and rapid recovery. The term ‘Great Depression’ is entirely accurate in the case of the US but not most other major economies.

The situation after the international financial crisis

Comparison of present trends since the international financial crisis of 2008 with those after 1929 immediately makes clear both similarities and differences. These may be seen in Figure 1 and can be summarised in three fundamental facts:

The fall in output in the advanced economies after the international financial crisis of 2008 was far less severe than after 1929 – the maximum fall in GDP after 2007 was only 3.3% compared to 15.6% after 1929.

However, after the 2008 international financial crisis there was no rapid recovery and strong growth as there was after the post-1929 collapse;

By 2016, nine years after the last pre-financial crisis year, the recovery from the crisis in the advanced economies was almost as slow as during the ‘Great Depression’ of the 1930s and by the end of 2017 it will be significantly slower. More precisely due to the slow growth by 2016, total GDP growth in the advanced economies in the nine years after 2007 was only 10.1%. By the end of 2017, on IMF predictions, the growth in the advanced economies after 2007 will actually be lower than after 1929 – total growth of 12.3% in the 10 years after 2007 compared to 15.1% in the 10 years after 1929. Furthermore, as analysed in the next section, IMF data shows that the future growth in the advanced Western economies after the international financial crisis will be far slower than in the same period after the 1929. IMF projections are that by 2021, fourteen years after 2007, total growth in the advanced economies will be less than half that in the 14 years after 1929 – average annual growth of only 1.3% compared to 2.9%, and total growth of 20.6% compared to 49.8%.

It is this very slow growth in the advanced economies since 2007 which means that the present period is best characterised as a ‘Great Stagnation’.(3)

2016-2021

For analysing trends after 2016 economic projections must be used. Those analysed here are the IMF’s latest projections made in April 2017. There are three reasons for using this data.

The IMF’s data on the advanced economies is not in any sense controlled by China or ‘anti-Western forces’ – there cannot be any accusation the data is biased against the West.

The IMF’s are the most widely used international economic growth projections;

IMF projections have persistently projected more rapid growth in the advanced Western economies than has actually occurred – particularly in the US.(4)

Taking the five-year predictions of the IMF for the period 2016-21, and making a comparison for the entire period 2007-2021 to the period after 1929, leads to clear and extremely striking conclusions:

From 2016-2021 the IMF predicts total growth in the advanced economies of 9.6% – an annual average 1.5%. Regarding individual countries, the IMF predicts annual average growth of 1.8% for the US, 1.4% for the UK, 1.2% for Germany, and 0.6% for Japan. Total growth for the advanced economies over the entire fourteen-year period 2007-2021 will be 20.6%.

In comparison, in the fourteen years after 1929 total growth in the advanced economies was 49.8% – growth in the advanced economies after 1929 was therefore more than two and a half times their projected growth in the fourteen years after 2007. (5)

To give a scale of comparison, and to confirm the character of the present period, only if annual growth in the period 2016-2021 rose to 6.4%, instead of the IMF’s projected 1.5%, would economic growth in the advanced economies in the 14 years after 2007 be equal to that in the 14 years after 1929 – such a scale of acceleration is evidently completely implausible. There is therefore an inescapable conclusion for characterising the present trend in the world economy:

The period 2007-2021 will see far slower average growth in the advanced economies than during the period after 1929 – i.e. the ‘Great Stagnation’ will see far slower growth over this period than the ‘Great Depression’.

It is correct to point out that rapid economic growth after 1938, the final phase of recovery from the crash of 1929, was not achieved by ‘normal’ peaceful means. The period after 1938 was characterised by massive state intervention in the economy to prepare for and then wage war. In particular, in the case of the US, as analysed in The Great Chess Game (一盘大棋? ——中国新命运解析): ‘the US state largely took over from the private sector as the driving force of fixed investment – by 1943 83% of US fixed investment was carried out by the state…. the most rapid period of expansion in US economic history, the one which established it as the undisputed economic superpower, was driven not by private but by state investment…. It was the ‘visible’ hand, not the ‘invisible’ one that propelled the US to a position of unparalleled global economic dominance.’

But this fact does not alter economic reality. Economic expansion produced by massive state intervention, or oriented to war, is still economic growth. Furthermore, this growth, with the exception of the US, built on the rapid recovery already taking place after the post-1929 collapse. Nor does it alter the fact that the period after 2007 will see far slower average growth than following 1929.

The reality is therefore clear. In terms of slowness of economic growth the ‘Great Stagnation’ will be worse than the ‘Great Depression’. Only the gigantic crisis surrounding World War I, in the whole history of modern capitalism, has seen a slower period of economic growth than that since the international financial crisis – the extreme depression of economic growth in that earlier period being due to the onset of World War I leading to a major decline in output in advanced economies. Clearly these facts of the deep stagnation of the Western economies has major strategic and immediate consequences for China – some of which will now be analysed.

Periods in China’s development

Having established the factual situation of the global economy first and most fundamentally such analysis of global economic trends makes clear the interrelation between international processes and China’s own development. The simultaneous existence of both international and domestic factors makes it clear why it is necessary to put forward an overall analysis of the present period.

Taking such a starting point integrating international and domestic developments, however, creates a somewhat different perspective on the periodization of China’s development than that sometimes used in China. More specifically:

Based on purely domestic events frequently in China five phases since the creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are noted – each corresponding to the chief figures in the country’s leadership of that period.

However, based on the interrelation of global economic developments with China, three fundamental periods may be seen since the creation of the PRC – these being 1949-78, 1978-2008, and from 2008 onwards.

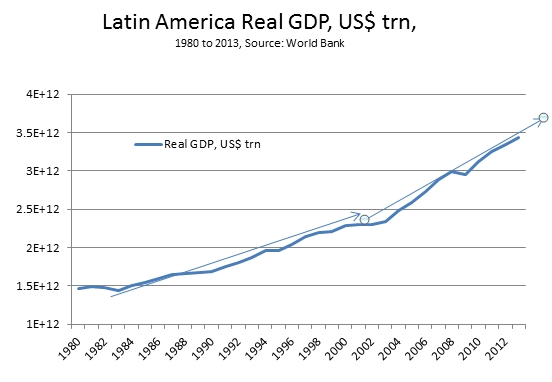

The three fundamental phases during the development of the PRC, in their interrelation with international trends, may be clearly identified by analysing the relation of trends in China with these different periods in the global economy. To illustrate this Figure 2 shows these periods and gives data on the advanced economies prior to the creation of the PRC. Exact dating is analysed below, and there is naturally some very small differences in precise timing between phases internationally and those in China, but the fundamental periods in the development of the international economy and their interrelation with China are clear. Taking first the global economic trends these periods are:

- 1913-1950 – period of slow average annual growth in the advanced economies (2.0%)

- 1950-1978 – period of rapid average annual growth in the advanced economies (4.4%)

- 1978-2007 – period of slower but still relatively rapid average annual growth in the advanced economies (2.6%)

- Period commencing after 2007 – very slow average annual growth in the advanced economies (1.1% in 2007-16, and IMF projected 1.3% in 2007-21)

The data in Figure 2 therefore shows clearly why the situation since 2008 should be considered a new and integrated period in China’s development interrelated with a new period in the global economy.

Figure 2

Analysing these very sharp differences between fundamental periods in the global economy also demonstrates clearly the interconnection of international developments with those in China. To show this interconnection:

First the fundamental periods in the development of the global economy and their interrelation with China will be briefly considered;

Then the light these trends cast on the features of the present situation will be analysed.

Four periods in the development of the international economy

The four distinct economic periods in the global economy during the last century each also had clear consequences for and was interrelated with trends in China. In chronological order:

- The first period, commencing after 1913, is the crisis of the international economic system marked by World War I, the 1929 crash, and World War II – this period of fundamental instability definitively ended with the beginning of the stable post-World War II boom in the advanced economies. This period was characterised by radical fragmentation of the world economy both by war and by generalised protectionism after 1929. The starting point of this period is World War I while its international conclusion, the commencement of a stable post-World War II boom, may be put at approximately 1950. Developments within China culminating in the creation of the PRC were clearly not autonomous from these processes in the international economy but were related to international events and their geopolitical consequences. The creation of the PRC in 1949 was directly related to this period – its culmination in a fundamental historical sense. During this historical period, average annual growth in the advanced economies was low – an annual 2.0%. However, this was not a low stable average but the statistical result of extreme fluctuations between strong booms and severe recessions. This overall international period may therefore be taken as 1913-1950.

- The second global period is the stable post-World War II ‘golden age’ boom in the advanced Western economies. The pure ‘boom’ phase of this, characterised by relatively uninterrupted rapid economic growth in all major advanced economies, was from 1950-73 – during this period ‘Keynesian’ economic techniques were dominant in Western economies. After 1973 there was economic instability, following which in 1979/80 a radically new economic policy was embarked on by Reagan/ Thatcher – with the reintroduction of ‘neo-liberal’ methods into the Western economies and a clear break with Keynesianism. Almost simultaneously in 1978 China embarked on a radically new, and very different economic policy to neo- liberalism, with a ‘socialist market economy’ created by ‘reform and opening up’. This economic period could therefore be taken as either 1950-78, in line with domestic Chinese developments, or as 1950-1980 in line with international ones – the last date being Reagan’s election. As this article’s focus is the interrelation of international with China’s domestic trends 1950-78 will be used for statistical purposes – although it would make no major difference if it were defined as 1950-80. During this period 1950-78 average annual growth in the advanced capitalist economies was high at 4.4% and until 1973 without severe recessions. In China, this was the period of the planned economy which produced average economic growth only very marginally higher than that for the world economy – in the period 1950-78 world economic growth was 4.6%, growth in the advanced economies 4.4%, and China’s growth 4.9%.

- The third economic period lasted from 1978 to the onset of the international financial crisis in 2008. In the advanced economies, this period was characterised by the neo-liberal policies inaugurated by Reagan/Thatcher and in contrast in China by the ‘socialist market economy’ policies inaugurated by Deng Xiaoping. In this period growth in advanced economies slowed significantly compared to the post-war boom, to an annual average 2.6%, but remained higher than the period of deep crisis commencing with World War I. In this period, China’s socialist market economy model far outperformed neo-liberal policies in the advanced economies – China’s annual average growth in 1978-2007 being 9.9%. To enable a comparison with analysis more usually used in China, it may be noted this internationally defined period 1978-2007 takes in most of three of the domestically defined five leadership periods.

- In 2008, the international financial crisis commenced. As already analysed growth in the advanced economic since then is extremely low – an annual average 1.1% in 2007-2016 and on IMF projections 1.3% in 2007-2021. This average growth rate is actually significantly lower than in the period of great crisis in the advanced economies commencing with World War I. But the low average in the present period is created, after the 2007-2009 recession, by very slow but relatively stable growth rather than a low average created by extreme fluctuations of boom and recession seen in the crisis commencing with World War I. Because of this extremely slow recovery after the international financial crisis the term ‘Great Stagnation’ most fits the present period since 2008. This phase in the global economy, of course, provides the international context for the ‘new normal’ in China.

The interrelation between international and domestic factors for China is clear in all these periods – the aim of the earlier part of this article being merely to establish the international features of the third period of this development starting with the international financial crisis of 2008. To be precise:

- No serious scholar suggests that the PRC’s creation in 1949 was unrelated to the great period of international crisis starting with World War I, proceeding through the Great Recession after 1929, and culminating in World War II.

- All analysis in China notes the great turning point of 1978 and Deng Xiaoping’s ‘Reform and Opening Up’. While in some literature insufficient attention is paid to the fact that this coincides almost exactly in time with the great turn in the Western economies in 1979/80 inaugurated by Reagan/Thatcher the present writer’s experience is that immediately this is pointed out Chinese scholars note that such a fundamental turn in both China and the Western economies occurring at almost exactly the same time cannot be a coincidence. Whatever explanation is then given it is therefore evident that 1950-1978/80 constitutes a period in the history of both China and the Western economies and a new one started with 1978/80.

- It is noticed inside and outside China that the international financial crisis of 2008 was the greatest peacetime financial crisis since 1929. But in some analysis this is inaccurately treated, explicitly or implicitly, as simply a temporary episode, a somewhat large ‘blip’ in the advanced economies which will be followed by a ‘return to normal’. Put in terms of a comparison to a well-known discussion in China it is explicitly or implicitly suggested that the advanced economies after 2007 entered a ‘V’ shaped period – a sharp downturn followed by a return to a relatively rapid rate of growth.(6) It has instead been established earlier in this article that, to make a comparison to discussion in China, in terms of growth rates the advanced economies after 2007 entered more an ‘L’ shape – a downturn without this being followed by a return to a rapid average rate of growth. The facts given demonstrate that the years since the international financial crisis of 2008 constitute a single historical period characterised by a new low average growth rate in the advanced economies. This constitutes a new period of the international economy and therefore its interrelation with China.

It is clear this situation in the advanced Western economies has major implications for the situation which confronts China. It is also for this reason, as analysed above, that the development of the PRC from the point of view of international trends may be analysed as in three periods:

In that framework, China’s current policy is a response to this new period since the international financial crisis.

Key trends in the new international period facing the Chinese economy

The fact that China faces a protracted period of slow growth in the advanced economies establishes a coherent link between the overall character of the period and immediate events. It also shows that international initiatives by China are not individual or uncoordinated but form a coherent pattern. However, to complete this picture these international trends must be integrated with cumulative Chinese domestic economic achievement – because it is clear that each of these fundamental international periods also corresponds to a phase of China’s domestic development:

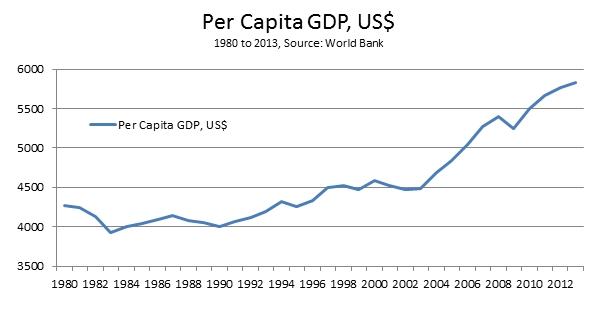

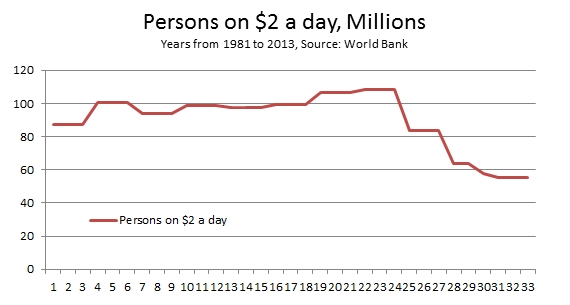

- 1949-78 in China was a period of a ‘social miracle’ without precedent in world history. Life expectancy, well known in economics as the most sensitive overall indicator of social conditions, as it sums up in a single figure all positive trends (prosperity, good education, good health provision, environmental protection etc.) and negative trends (poverty, poor education, bad health care, pollution etc.), rose in China by 29 years from 1949 until Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 – from 35 to 64. China’s life expectancy increased by more than one year for each chronological year that passed, rising from 73% of the world average in 1950 to 105% in 1976. However, this period’s stupendous social achievement was not accompanied by exceptionally rapid economic growth. As already noted in 1950-78 China’s overall GDP growth was only marginally above the world average – China’s GDP rose by an annual average of 4.9% compared to a world average of 4.6%, and China’s annual average increase in per capita GDP was 2.8% compared to a world average of 2.7%.

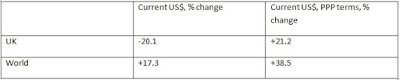

- In 1978-2007 China’s socialist market economy far outperformed the economic growth rate of the Western economies – China’s annual average GDP growth rate was 9.9% compared to 2.6% in the advanced Western economies. By this very rapid economic growth China successfully achieved the transition from a ‘low income’ to an ‘upper middle income’ economy by international classification – and was taken to the threshold of achieving ‘high income status’.

- The period from 2008 onwards has seen China rise towards achieving ‘moderate prosperity’ by 2020 and attaining ‘high income’ status by World Bank criteria shortly thereafter. In short, the period of the ‘Great Stagnation’ in the Western economies will simultaneously see China rise into the ranks of high income economies – this transition to ‘moderate prosperity’ and then to ‘high income’ status by international criteria constitutes a key domestic feature of the present period.

In summary, this new period since 2008 is characterised by:

- From the domestic economic viewpoint, the transition of China from ‘high middle income’ status to ‘moderate prosperity’ and then ‘high income’ status by international criteria.

- From the viewpoint of international economic development by very slow growth in the advanced Western economies.

This combination is of course in economic terms significantly different to either of the earlier periods 1950-78 or 1978-2007.

Implications of the new period

There are numerous implications from the interaction of these domestic Chinese factors and the current extremely slow growth in the Western economies, which are too numerous to analyse here, but the following provide key examples. First, purely economic trends will be analysed, then their geopolitical consequences, and finally their implications and attractions for countries other than China:

- The characteristic of the present period in the advanced economies is slow average growth but not violent oscillations of expansion and crash – as in the last period of very slow growth in the advanced economies commencing with World War I. While no major acceleration of the advanced economies is to be expected neither is there reason to anticipate a massive economic crisis of the 1929 type – the crisis commencing with World War I was produced by the disintegration of the global economy amid both war and then after 1929 due to generalised protectionism. These conditions do not currently exist. Prolonged slow growth in the advanced economies, not sudden deep crisis, is therefore the central perspective.

- As China faces a substantial period during which growth in the advanced Western economies will be low, while no sharp crisis is expected the prospects for the growth rate of China’s exports to these countries will be relatively limited.

- Continued slow growth of the US economy creates protectionist trends within it – although other advanced economies, most importantly in terms of size the EU, remain strongly opposed to this.

- These international trends provide the overall global context for China’s ‘new normal’.

To avoid any misunderstanding, it should be made clear that this analysis, as with all others in this article unless otherwise specified, is of medium term economic trends. The average very slow growth in the advanced economies in the period since the international financial crisis does not mean that there may not be individual short phases of somewhat faster growth within an overall period of slow growth. For example, as

analysed in ‘The economic logic behind Trump’s foreign policy – why the key countries are Germany and China’ US economic growth was so slow in 2016, at 1.6%, that it is likely that there may be some improvement in 2017 for purely statistical reasons. What is precluded by overall trends is a major sustained upturn in growth. What are dealt with here are cumulative characteristics of the period as a whole, not purely short term economic predictions.

Turning from purely economic trends to geopolitical consequences:

- As advanced economies are in a period of very slow growth US neo-cons, and others who think not in terms of ‘win-win’ outcomes but of zero sum games, cannot deal with rising ‘competitors’ such as China by accelerating their own economies. The competitive strategy of those such as US neo-cons which think in such negative terms therefore has to be to attempt to slow other economies such as China. This point is analysed in detail for US relations with China in 一盘大棋? ——中国新命运解析. In relation to China, this means that the previous US strategy was to attempt to undermine and disintegrate China by fake campaigns on ‘human rights’, finding and supporting a ‘Chinese Gorbachev’ etc. – i.e. centring on political offensives. This perspective was, however, almost immediately blocked by Xi Jinping with the ‘four comprehensives’, the emphasis on the role of the Communist Party of China (CPC) etc. Given the present situation of the US and advanced economies, which precludes any major sustained acceleration in economic growth, US neo-cons have instead to seek to achieve their strategic goals by attempting to slow and create crisis within China’s economy.

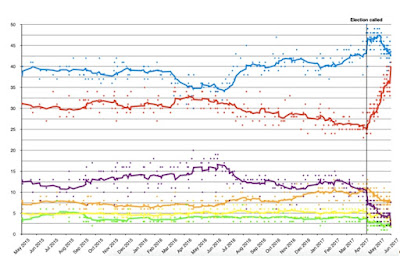

- A prolonged period of slow growth in the advanced economies necessarily creates political instability within them. Developments such as Trump’s coming to office against the wishes of the majority of the US political establishment, the UK’s economically irrational Brexit decision, the lesser but still significant upheavals in other Western countries (e.g. rise of Le Pen’s National Front in France, ‘left’ leaders such as Sanders or Corbyn, strength of overtly xenophobic currents in a number of EU states etc) must therefore not be understood as temporary but should be expected to persist.

- Given very slow growth in the advanced economies, the US is less able to use its old post-World War II/Cold War policy of large scale economic aid to developing countries to stabilise them – i.e. the US is less able to use an economic ‘carrot’ as well as a militarily ‘stick’. The US is therefore increasingly forced to rely solely on military force in attempting to ensure carrying out of its policies in developing countries. This policy, shown in the bombing of Serbia, invasion of Iraq, and the bombing of Libya would be further intensified if Trump’s budget policy of drastic reductions in foreign aid and large increases in military expenditure is ratified by the US Congress.

- While a number of major developing economies continue to grow rapidly, very slow growth in major advanced economies necessarily produces stagnation and chaos in some weaker developing economies or those which are struck by side effects of the advanced economies slowdown – for example oil and commodity producing states are severely affected by low commodity prices. This produces social instability and in some cases war. An area defined by different levels of military conflict now extends from West Africa, through parts of North Africa, into the Middle East, upward into Ukraine and, stepping over relatively stable Iran, into Afghanistan. Given the slow growth in the advanced economies, and the inability of the US to pursue its old post-World War II policy of using economic means to stabilise situations, such instability and military conflicts may be expected to continue in the coming period – although the regions and countries in which such conflicts take place may change. US foreign policy has shown, in Iraq and Libya, that in a number of cases it prefers ‘failed states’, even if this leads to strengthening of ‘jihadism’, to the existence of stable regimes which do not follow US interests. This clearly has geopolitical and even military consequences for China.

- There is a danger that a situation where the US is unable to break out of its slow economic growth, which faces acute political instability in parts of the less developed world, and in which China’s growth continues to far outperform it, will result in US military measures to attempt to resolve the problems facing it. The facts of the global economy make clear that Ian Johnson’s warning of an economy which ‘continues to stagnate’ and therefore of the risk of ‘overseas adventures and blaming foreigners for the country’s woes’ is highly accurate – but it applies to the Western economies. The strengthening of China’s military forces is therefore extremely necessary, and in the interests of global peace, as a counterbalance to the risk of such military adventurism by the US. The emphasis on modernisation and strengthening of China’s armed forces is a necessary response to this. Equally other countries, therefore, have an interest in the success of China against dangerous and adventurist tendencies which potentially flow from trends in the Western economies.

So far, the interrelation of the international economy and China has been analysed primarily from the angle of its consequences for China. However, there is of course an increasingly strong causal effect in the opposite direction – the impact of China on the global economy and on countries outside China. This in turn naturally affects China itself. This causal effect has grown greatly due to two mutually reinforcing processes since 2007:

- The increasing weight of China in the world economy;

- The slow growth in the Western economies.

The result of these processes is that in PPP terms from 2007-2016 31% of world GDP growth was due to China, compared to 10% for the US – at current dollar exchange rates 44% of world GDP growth from 2007-2016 was due to China. The IMF projects that in PPPs 27% of world GDP growth in 2016-2021 will be due to China compared to 14% for the US.

A new feature of the present period is therefore the very strong direct impact of China on the world economy and the objective interest of other countries in cooperating with this. This fact provides the clear interconnection between key international initiatives launched under Xi Jinping.

- The emphasis on a ‘community of common destiny’ is correct from a fundamental theoretical and long term viewpoint – as it flows from the fact that the advantages of division of labour mean international economic cooperation is mutually beneficial. This cooperation corresponds to the reality that in economics, due to the advantages of international division of labour, ‘one plus one equals more than two’ and therefore there exist in reality ‘win-win outcomes’, not the ‘zero-sum game’ concept of US neo-cons. But more immediately the concept of a ‘community of common destiny’ is also opposed to the protectionist strategy of key members of the Trump administration. It is for this reason that Xi Jinping’s speech to the Davos World Economic Forum earlier this year emphatically defending globalisation received widespread international support.

- Slow growth in the advanced economies creates the specific form of relation of other countries to both China and the US. China’s economy is much more rapidly growing than the US but the US retains global military superiority. Therefore, China’s attraction for other countries is strongly economic while the US possesses military power. Put in aphoristic terms China offers other countries inclusion in OBOR, or the AIIB, whereas the US offers the ‘stick’ of a military attack or the ‘carrot’ of military alliance.

- The slow growth analysed above is specifically of the advanced economies. Growth in the developing economies is much faster. A specific characteristic of the present economic period is therefore of slow growth in the advanced economies and much more rapid growth in a number of developing economies. This clearly shows the strategic importance of key initiatives for China such as OBOR, the AIIB, the BRICS bank etc. The growth potential of the OBOR region, in both percentage and absolute terms, is much greater than either that of North America and Europe – giving other countries a strong incentive to participate in its benefits.

- Very slow growth in the advanced economies provides the context of the ‘Washington Consensus’, which continues to be promoted by the US but which facts show has been far less successful in producing economic development than China’s socialist market policies and the increasing number of countries influenced by this – a detailed analysis of this was given in 世行数据中隐藏着一个秘密. It is therefore important that China actively promote its economic policies internationally. More rapid international economic growth resulting from this naturally benefits China but also aids those countries experiencing such growth.

Conclusion

The above data demonstrates that once the factual situation of the global economy is analysed the various trends of the present period are not separate but integrated and interrelated with domestic trends in China. Nor is China’s response to them simply a series of individual initiatives. On the contrary it flows coherently from the fundamental character of the new period of the global economy and its interrelation with China.

It should be noted that accurately understanding the trends operating both internationally and within China corresponds to the requirement in both Chinese and advanced Western thought that any situation must be understood in terms of the totality of forces operating in it – which includes both domestic and international ones. This is opposed to an erroneous analysis which attempts to analyse a situation by looking only at one or a few (normally domestic) forces operating in it.

As an aside it may be noted that this shows the continuing contemporary importance of Mao Zedong thought for analysis in China. For it was Mao Zedong who gave the most precise analysis of this requirement in his famous essay ‘On Contradiction’:

‘To be one-sided means not to look at problems all-sidedly, for example, to understand only China but not Japan, only the Communist Party but not the Kuomintang, only the proletariat but not the bourgeoisie, only the peasants but not the landlords, only the favourable conditions but not the difficult ones, only the past but not the future, only individual parts but not the whole, only the defects but not the achievements, only the plaintiff’s case but not the defendant’s, only underground revolutionary work but not open revolutionary work, and so on… There are many examples of materialist dialectics in Shui Hu Chuan, of which the episode of the three attacks on Chu Village is one of the best.

‘Lenin said: “… in order really to know an object we must embrace, study, all its sides, all connections and “mediations”. We shall never achieve this completely, but the demand for all-sidedness is a safeguard against mistakes and rigidity.”…

‘To be one-sided and superficial is at the same time to be subjective. For all objective things are actually interconnected and are governed by inner laws, but instead of undertaking the task of reflecting things as they really are some people only look at things one-sidedly or superficially and who know neither their interconnections nor their inner laws, and so their method is subjectivist.’

Applying this method to an integrated analysis of tendencies in the global economy and within China shows clearly the trends operating casts a clear light on the global economic perspectives facing China. Whether such an international analysis of the three fundamental periods of China’s development in relation with the international economy is useful for China itself is naturally is not for someone who is not Chinese to decide. However, it is clarificatory internationally in understanding the relation between trends in China and the fundamental periods of development of the global economy.

* * *

Notes

(1) The most notorious example of such ‘econofiction’ is Gordon Chang’s ‘The Coming Collapse of China’, the most widely quoted recent example is David Shambaugh’s ‘The Coming Chinese Crackup’, and a typical wild diatribe was by Ian Johnson in the New York Review of Books claiming China’s ‘economy continues to stagnate’ creating risk of ‘overseas adventures and blaming foreigners for the country’s woes.’ Such claims have been repeated for decades regardless of how regularly they are refuted by events.

(2) The term ‘advanced economies’ prior to 1980 constitutes the main advanced economic centres – the US, Western Europe, and Japan – plus Canada, Australia, and New Zealand as defined in Maddison’s Historical Statistics of the World Economy 1-2008 AD. After 1980, the IMF data from World Economic Outlook October 2016 adds to these countries a few economies which have more recently attained advanced economy status – e.g. South Korea and Singapore. However, the US, Western Europe and Japan are so overwhelmingly dominant in terms of weight within the advanced economies that this small geographical expansion makes no substantial changes to the results.

(3) The present author wishes to make clear the term The Great Stagnation is used by Tyler Cowen as the title of a book. However, Tyler Cowen’s explanation of this stagnation is rooted in technology and entirely different to the data given here.

(4) Regarding the last point, it is an elementary rule that in analysing a development assumptions least favourable to a argument being tested should be used. If the IMF had underestimated growth in the developed economies use of its projections could be interpreted as excessively ‘pessimistic’. However, successive IMF forecasts, in its biannual World Economic Outlook, have over predicted growth in the advanced economies. Even more strongly, as will be seen, the trends are so clear that any deviation from IMF predictions within any reasonable order of magnitude would not alter the fundamental perspective.

(5) Taking the individual countries growth in the US in the 14 years after 1929 was 87.8%, in Japan 67.4%, in Germany 58.1% and in the UK 50.3%. In the years 1938-43 itself growth was exceptionally rapid. For the advanced economies as a whole total economic growth in the period was 39.5%, or an annual average 6.9%. Annual average growth in the UK in 1938-43 was 4.9%, in Japan 4.0% and in Germany 3.9%. In the US growth in the five-year period 1938-43 was an extraordinary 97.8%, an annual average 14.6% – the fastest growth over a five-year period in a major economy in human history.

(6) This perspective is suggested by the term ‘Great Recession’ which, in contrast to ‘Great Depression’, suggests a downturn followed by a ‘return to normal’

Recent Comments