.309ZThe money exists for investment in GreeceBy Michael Burke

The fraught negotiations between the new Greek government and representatives of the EU institutions are likely to be prolonged. They have centred to date on Syriza’s efforts to find room to alleviate some of the worst effects of austerity and address what is called the ‘humanitarian crisis’.

This is entirely justifiable given the depth of the fall in living standards with widespread malnutrition in Greece, a health crisis, hundreds of thousands of homes cut off from electricity supply and other ills.

Policies aimed at income redistribution can help in this key area, so it is entirely correct to attempt to increase tax revenue from the rich in order to ameliorate the effects of poverty on the poor. But any sustainable improvement in living standards must be based on increasing the productive capacity of the economy which requires investment. Any transfer of income will be a one-off effect if income does not grow. Yet the austerity measures imposed by the Troika (EU Commission, European Central Bank and IMF) and the existing burden of debt interest payments prevent the government from investing and provide a further disincentive for the private sector to invest of its own volition.

Domestic sources of investment

There are two key sources of funds that could be tapped for investment; domestic and international.

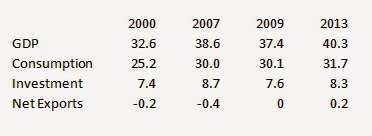

Domestically the Greek business class claims the highest share of national income in the whole of the OECD. In 2013 (in nominal terms) the Gross Operating Surplus of Greek firms was €102.2bn from a GDP total of €182.4bn. This profit share in GDP of 56% is way in excess of the customary levels in the OECD. By comparison the German profit share in the same year was 39.3%.

A high profit share is not itself directly harmful to growth and prosperity. If firms were investing profits the productive capacity would be rising rapidly and new high-quality and high-paid jobs could easily be created. But the opposite is the case in Greece, which also has the lowest rate of investment as a proportion of GDP in the whole of the OECD. Again in nominal terms investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) in Greece in 2013 was just €20.5bn or 11.3% of GDP. By comparison the German proportion of investment was 19.8%.

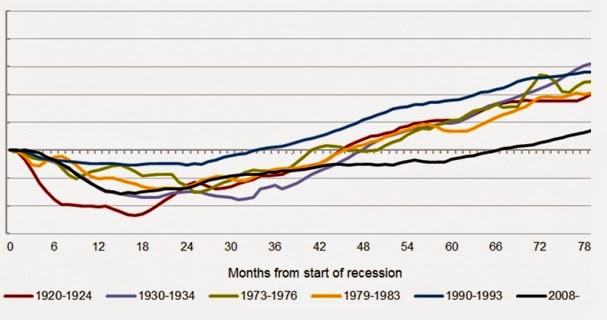

This is not to hold up the German economic model to be emulated. Like all the Western economies (including Britain) the rate of investment in the German economy has slowed dramatically over several decades, which is the cause of the ‘secular stagnation’ of the Western economies over the same period.

Even so, the disparity in the profit rate and the investment rate is exceptional in Greece. The proportion of uninvested profits in Germany is equivalent to 19.5% of GDP (profits equal to 39.3% of GDP minus an investment level equivalent to 19.8%). This level of uninvested profits is very high by historical standards. But the proportion of uninvested profits in Greece is 44.7% (profits of 56% of GDP minus investment of 11.3%). The nominal level of profits and investment is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Fig.1 Profits and Investment in Greece, 1990 to 2013, €billions (nominal terms)

The charge of indolence and feckless aimed at Greek workers, which is a slur repeated and not solely confined to northern European tabloid newspapers, is entirely misplaced. It is Greek capitalists who refuse to invest a vast proportion of profits who have caused both long-term low productivity growth and the relative crisis. This is true not just on a relative basis but also on a historic one. In 1990 Greek investment was equivalent to 42.8% of profits. In 2013 it was just 11.3%.

International sources of investment

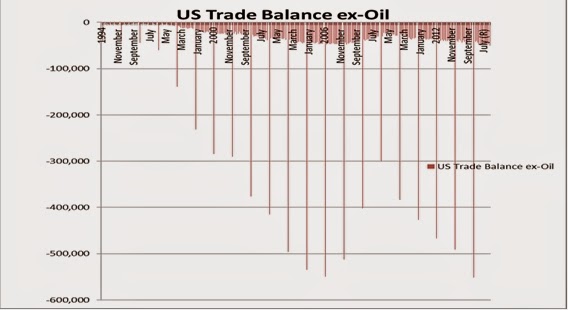

A structural flaw in the Euro Area economy is that it represents an effort to create a single, continental-sized economic entity to compete with the scale of the US and Chinese economies by purely monetary means. The Euro Area has a single exchange rate and single short-term interest rate. But fiscal policy remains overwhelmingly as a national responsibility.

This is a structural flaw as all economic development is uneven. An exchange rate or interest rate policy which may be appropriate to the average will necessarily cause dislocations or worse to economies whose level of development differs significantly from the average. In all other modern economies fiscal transfers occur between regions, usually automatically via common tax and spend systems. In the United States, a federal system of taxation and transfers does not prevent individual states levying their own taxes or making transfer payments (social security, subsidies to farms, etc.). But these federal transfers amount to more than 10% of US GDP.

The EU and the Euro Area have both had fiscal transfers. These have been set through the European Social Fund, the Common Agricultural Policy and others but have usually amounted to little more than 1% of GDP. Disastrously, they have also been cut at a time of crisis, which David Cameron and others boasted as an achievement. The 7-year budgeting round has seen the 2014 to 2020 European Social Fund cut from €961bn to €367bn in nominal terms. The European Regional Development Fund will be €453bn, an increase from €347bn over the preceding period. But this does not compensate for cuts elsewhere and inflation further erodes the total. It is also widely misunderstood that big countries are also recipients of EU funds. Fig.2 below shows for example that Germany received twice as many as ESF funding as Greece over the period 2007 to 2013.

Fig. 2 National Distribution of ESF funding 2007 to 2013, € billions

Source: EU Commission

The cuts to internal transfers have taken place at the worst conjuncture, coinciding with the gravest economic conditions in Europe since the aftermath of World War II. The cuts will accelerate centrifugal tendencies with the EU and unless the trend is reversed they will be key factor in the potential of a break-up of the Euro Area.

While this is a strategic issue, which would need to be addressed by a supplementary budget, there are funds at hand which could immediately be deployed in Greece. One of the many large funding institutions sponsored by the EU is the European Investment Bank (EIB), which has ample scope to increase lending.

As part of a general trend, the EIB has not provided funds for investment that could have alleviated the crisis despite having the financial capacity to do so. Prior to the crisis in 2007 the main components of the EIB’s balance sheet were capital of €35bn and borrowing of €276bn. From this it had made outstanding loans of €285bn. By 2013 the bank’s capital had increased substantially but the growth of its loan portfolio has lagged significantly.

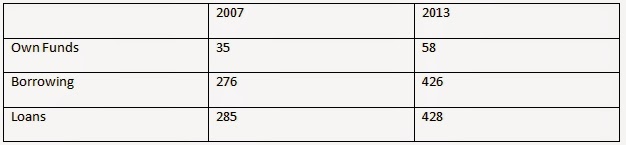

Table1. Key components of EIB’s balance sheet, €bn

Source: Author’s calculations, EIB annual reports and accounts

The EIB is part of an elite group of the world’s most highly-rated borrowers, with a very high capital buffer (own funds) and the explicit guarantee of all the EU governments. As a result it can borrow at extraordinarily cheap interest rates. Maintaining the same ratios as in 2007 and based on the increase in its own funds since it could raise its borrowing to €457bn and its loan portfolio to €472bn.

Given the immediate priority is reviving the Greek economy this could easily be the recipient of the extra €45bn in funds for investment that would become available. A similar pattern applies to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which mainly lends to Eastern Europe (pdf). Since 2011 new investment in projects has fallen by €9bn even though bank capital has increased by €1.7bn. But funds are needed to both develop and integrate the region with the richer West and geographical reasons mean Greece should also be a key destination for that purpose.

Beyond Greece, the subscribing EU countries to both banks can now borrow at exceptionally low interest rates and earn far larger returns from the banks’ investments. Neither the EIB nor EBRD are charitable institutions. The focus for investment would be all the crisis economies of Europe East and West. But these sources of investment could also form part of the overall solution both to the investment crisis and the growing strains on the Euro Area and European Union economies.

Conclusion

There is a pressing need to address the humanitarian crisis in Greece. It remains to be seen how much breathing space Syriza’s fight can win from the EU institutions.

But sustainable growth requires investment. The trend of cutting investment and other transfers within Europe, and cuts to development lending fit with the general austerity policy across Europe of cuts to state investment which are exacerbating the private sector investment strike.

However, this not only deepens the current crisis but threatens to undermine the entire Euro and EU project from within. It is not only the Greek economy which is at stake; it is just the most extreme example of general trends.

Within Greece the key source of funds for investment are the uninvested profits of the business sector. Internationally, EIB and EBRD funds already exist for major infrastructure and other forms of investment. These should be tapped immediately to rescue the Greek economy. And much larger funds could be applied to all the crisis countries of Europe, in a win-win for them and for the key investing countries. The alternative is ongoing crisis and increased risk of Euro break-up.

Recent Comments