6992,00.html”>Above $4 a day people can also begin to move beyond basic necessities and establish at least some quality of life. Most important of all average life expectancy at birth has risen by 3 years, from 71 years to 74 years. This is the most fundamental social indicator of all indicating improvement in living conditions and prosperity and is only possible with a combination of increased access to a range of foodstuffs, improved healthcare and housing.

There are a large number of indicators of poverty reduction and social progress which point in the same direction, although some important indicators of the position of women have not improved or have even gone backwards. These are significant omissions which need addressing. But taken as a whole the improvement in the economy, the general well-being of the population and its poorest members have also shown remarkably rapid and dramatic improvement since the beginning of this century.

Source of growth

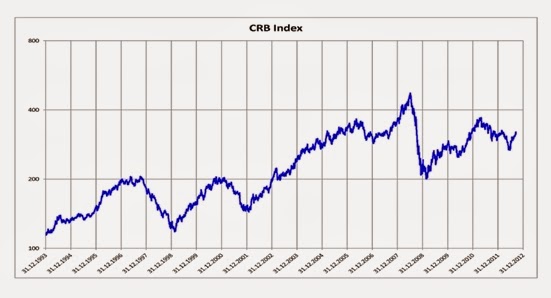

Many Latin American and Caribbean economies are exporters of basic commodities. Like all commodity producers they benefited from the strong rise in global commodity prices in the early years of this century. The increase in commodities’ prices is illustrated in Fig. 4 below, as the commodities’ research Bureau (CRB) aggregates a basket of many of the key commodities’ prices, which doubled in price over the period.

Fig.4 CRB Commodities Index, 1993 to 2012

Source: Reuters/CRB

However the widespread assertion that exports were the sole or even main contributor to regional growth is a misconception. The accurate picture is that the increased export earnings from rising commodities prices were a catalyst for growth in general but that this growth was led by investment. This is shown in Table 1 below which itemises the growth rates for GDP and its components since the beginning of this century.

Table 1. Latin America & the Caribbean, Growth of GDP & Its Components, 2000 to 2016 (Forecasts)

For most of the period 2000 to 2012 exports were one of the weaker components of GDP growth. Over the period as whole they grew more slowly than GDP itself. Furthermore for the entire period exports grew more slowly than imports. As a result net exports actually subtracted from growth.

The leading component of growth was fixed investment. This conforms to economic theory, where the amount of capital deployed and the growth of the workforce and its quality (via training and education) account for the overwhelming bulk of growth. In the most accurate terminology, fixed investment is the accumulation of the productive capacity of any economy. As previously noted, both consumption and living standards improved dramatically over the period. But consumption cannot be an input into growth. If consumption growth exceeds output, it can only be sustained by increased indebtedness which actually leads to lower living standards. The increase in both private and public consumption was only made possible through the sustained increase in fixed investment, which was the strongest component of GDP growth by some distance.

It was only in 2010 and 2011 that exports grew more strongly than GDP. This was a result of global quantitative easing led by the US and the modest recovery in the leading economies which had the effect of driving up global commodities prices even further. But this produced its own negative effect. 2012 was the first year where fixed investment growth lagged GDP growth and the economy has slowed since. As resources are diverted away from investment economic slowdown inevitably follows.

Problems caused by the US

The period 1980 to 2000 was a lost generation for Latin America. The US had overthrown the Allende government in 1973 and held sway over the continent mainly through its alliances with brutal military dictatorships. The revolts against the dictatorships in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Grenada were all blocked or overturned by the US or US-backed forces.

It was this US dominance in the region which paved the way for economic collapse. The US had unilaterally withdrawn from the Bretton Woods currency system in 1971, provoking a global spike in commodities’ prices. It was forced to do so because it was unable to finance both the Viet Nam war and domestic consumption at the prevailing exchange rate. This fall in the US Dollar/rise in commodities’ prices resulted in a huge increase in the Dollar export earnings of the oil producing states, concentrated in the Arab world.

The oil producers, led by Saudi Arabia effectively bailed out the US through a huge inflow of those earnings in the form of ‘petro-Dollars’ into US banks. As well as financing US budget and trade deficits these funds were also used to boost US banks overseas lending, especially in Latin America.

The global downturn of the late 1970s left these borrowers exposed, primarily government borrowers. A full-blown currency, debt and economic crisis was marked by the Mexican government’s debt default in 1982. At US insistence, it was the US banks that were rescued, not the Latin American economies, through the issuance of ‘Brady Bonds, named after the US Treasury Secretary. Debt crises in a host of other countries followed and the resulting debt burden sucked capital from South to North over the following decades and led to economic stagnation and misery.

These gyrations are not solely of historical interest. The role of the US Dollar as the major reserve currency and the denominator for virtually all globally-traded commodities means that significant or abrupt changes in US economic and monetary policy are magnified in commodity-producing and/or debtor economies. Sharp changes in US monetary policy always lead to sharp dislocations in the rest of the world, especially in ‘emerging markets’. As the US is also the world’s largest net debtor economy, it has a constant necessity for inflows of overseas capital. In periods of economic expansion this need increases sharply. Changes in US monetary policy are conditioned by this requirement for capital generated in the rest of the world and so can cause abrupt and hugely dislocating flows of capital in other countries.

This is precisely what has happened in the most recent period. The US Federal Reserve Bank ended its third round of quantitative easing on October 29. This had helped to inflate financial assets included commodities prices from 2010 onwards. Now the US is consciously aiming to drive down key commodities’ prices. The US has agreed with the key oil producer Saudi Arabia that the oil price should fall. On the US side this is an extension of the sanctions against Russia, but it welcomes the collateral damage to countries such as Venezuela, where sanctions are now also threatened.

New challenges

Politics comes before economics. The economic transformation of an entire continent cannot happen randomly. Across the region (with certain exceptions) through decades of upheaval a political leadership has been forged that rejected the dominance of the US and its neoliberal economic policies. The period 2000 to 2002 was marked by the sharp turn of Hugo Chavez’s revolutionary government in Venezuela towards Bolivarian socialism, ending generations of national humiliation. Shortly afterwards the serial humiliations inflicted on Argentina hit a brick wall with its default. Then in 2002 the Lula and the Brazilian Workers’ Party won the Presidential election.

Although they represent different social coalitions their common platform is a desire for economic growth, and the improvement of the living standards of the population, in particular the poorest layers of society. In different ways they draw inspiration from the Cuban revolution and its determined resistance to US rule.

It is important to stress that economic redistribution was an outcome made possible by growth. It was not the driver of it. The principal economic contributor to the economic transformation was the rise in fixed investment. Until 2012 fixed investment was the strongest component of growth and was its leading element. Growing trade, including intra-Latin American trade was a key catalyst for investment-led growth. This in turn allowed the growth of both public and private consumption, which indicates the general rise in living standards.

But the catalyst of rising export revenues has gone into reverse. At the time of writing the CRB Index had fallen to 247, close to levels last seen at the depths of the crisis in 2008. The oil price has fallen below $65/bbl a new 5-year low. This is a direct consequence of changes in US policy. This is in effect a crisis of 2008/2009 proportions for most of the commodity-producing economies, which takes in virtually the entire continent of Latin America and the Caribbean.

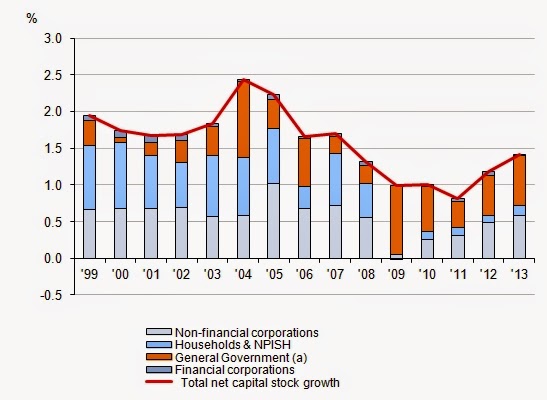

The growth of fixed investment has slowed to a crawl, which will prevent any sustainable revival of GDP growth. This is illustrated in Fig.5 below with reference to Brazil, which is by far the largest regional economy and accounts for nearly 40% of the entire continental GDP. This shows Brazilian Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) as a proportion of GDP, both the total and the specific contribution of the private sector. From 2002 onwards the long-term decline in the investment rate was being reversed. But there has been a renewed decline in 2012 (and other data suggest this has been extended since).

Fig. 5 Brazil GFCF, Total and Private Sector, % of GDP

Capital outflow

There is also a new threat in the form of capital outflow. The US is the dominant financial power in the world and the US Dollar the main currency denominator not only for commodities but also for international debt. Yet the US has a structural capital shortage, as shown by its chronic deficits on the balance of payments. In periods where US capital is seeking to expand, it is obliged to suck in capital from the world. The outflow of capital from ‘emerging market economies’ was recently the subject of a strong warning from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). This is a specific threat to the Latin American economies.

The BIS data show that Latin America and the Caribbean owe BIS-reporting banks (the banks of all the industrialised economies) a net amount US$1.337 trillion. Of this $565 billion is held in foreign currencies, which is virtually all in US Dollars. The overwhelming bulk of this US Dollar debt is owed by both private sector firms and banks based in the region and is owed to Western banks. US Dollar debt owed by governments is a relatively modest $113 billion.

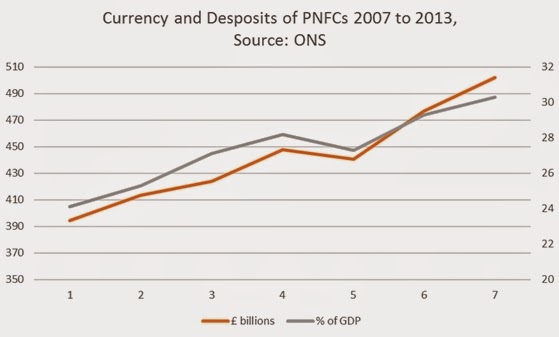

In addition to the challenge posed by falling commodities’ prices and the need to reverse the sharp slowdown in the growth rate of investment, it is the region’s private sector firms which are the Achilles Heel of the economy.

The regional firms and banks are no longer benefitting from the rise in exports and are primarily responsible for the sharp slowdown in investment. They are also the primary source of capital outflow from the domestic economies, and will in many cases be directly responsible for it. They are likely to come under severe pressure as they absorb the effects of lower exports, slowing domestic economies and rising debt-servicing costs. There is no point in minimising the scale of these difficulties. They amount to a new crisis for the entire region and need a new response.

Responding to the new threats

A revival of growth is vital for a return to rising living standards. Three key steps are required, each of them interrelated. Returning to per capita GDP growth depends first on reviving the growth of fixed investment. Secondly it is necessary to soften the blow of falling export prices by increasing trade diversification. This is both a geographical diversification as well as adopting measures to increase the value created in production by increasing the output of finished goods and manufactures, compared to basic commodities. Thirdly a series of strong defensive measures are needed to insulate the region from the US-driven outflow of capital.

The decline in fixed investment is primarily the responsibility of the private sector. Since private sector investment is determined by the anticipation of profits a spontaneous recovery cannot be relied on, especially in the current conditions. Therefore the state sector must increase its own level of investment. It can do so in a number of ways, including directing domestic banks to increase productive investment by cutting back on speculation or other useless activity. It can regulate the level of private sector firms’ investment by legislation and other means (including in the awarding of government contracts). It can also apply windfall or other confiscatory taxes to fund direct government investment. If the private sector resists any of these measures, all necessary steps can be taken to overcome that resistance, including nationalisation.

One of the great successes of the period of expansion has been increasing continental economic co-operation through a variety of regional bodies, including Mercosur/Mercosul and ALBA. This helps to break down colonial patterns of development, where nearly all international trade was formerly geared towards exports of basic goods to the US. The deepening of regional ties through increased trade and infrastructure projects can help to soften the blow of falling commodities’ prices. But it is also important to move higher in the value chain of production and away from basic goods. Over the long-term manufacturing has been in decline as a proportion of GDP across the region. Increasing regional value creation requires both development of the economic capacity and access to hi-tech investment products. Here the two key potential allies are the deepening of ties with China and Russia. The former can provide funding for regional infrastructure and both can provide access to hi-tech investment goods, vital to revival of manufacturing and increasing value-added.

The outflow of capital represents an immediate and significant threat to regional prosperity. National savings need to be protected from US predations. Strong counter-measures are required. These may include restrictions on financial trading, capital controls and taking state ownership and control of the banks where necessary, as they facilitate the highly damaging outflow of capital.

Conclusion

Latin America and the Caribbean have seen a remarkable transformation in the most fundamental of living standards of the population in the first decade of this century. The first condition was the forging of a political leadership capable of coming to power and ending US domination.

Economically they were able to achieve this as the commodity-producing economies of the region benefited from the global rise in commodities prices. But this benefit was used to fund investment, which was the leading component of growth. It was the rise in investment which allowed the rise in living standards.

Now commodities’ prices have gone into reverse. Yet it remains the case that only increased investment can lead to increased prosperity. Therefore new radical measures are required in order to fund investment. Continuing the transformation in distribution will require a transformation in production.

This is centred on the direction of private sector firms and banks operating in the region. They have reduced their level of investment in the face of falling commodities prices and a slowing economy. They are also the primary source of the potentially disastrous capital flight from the region, which is being orchestrated by the US to destabilise its enemies and for its own benefit. Only by directing their levels of investment can growth be resumed. In some cases taking ownership of some of these banks and firms can the governments continue with their policies of economic and social transformation.

Recent Comments