yesBritain’s trading performance is making us poorer

By Tom O’Leary

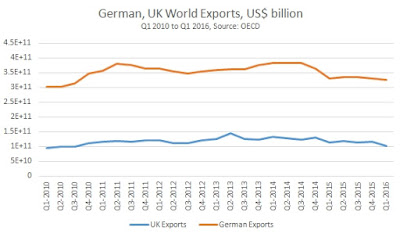

Britain is not a great trading nation, or more accurately is no longer a great trading nation. Its exports are just one third of Germany’s. As recently as 1988 UK exports as a proportion of GDP were larger than Germany’s exports on the same measure. Exports can be a key driver of growth, for all countries. It is therefore extremely important to understand how that can be achieved in Britain and what both the scale and the scope of the problem is.

Some simple maths

It is sometimes argued, in what is described as growing anti-globalisation sentiment, that all nations cannot have export-led growth, or that the growth of trade is itself in some way exploitative. Both of these views are quite commonplace and wrong.

If the world economy were a zero-sum game, it would of course be true that the growth of one country’s exports has its counterpart in the decline of another country’s exports. But the world economy isn’t a zero sum game. What it actually leads to is the growth of another country or countries’ imports. This distinction matters.

If something is growing, such as world trade, it is possible for all countries to have rising exports. Further, if something is growing faster than GDP, such as trade, it is possible for all countries to have exports rising as a proportion of GDP.

This is exactly what has happened. Table 1 below shows the proportion of exports in the GDP of selected leading economies. In all cases exports have risen as a proportion of GDP.

Unfortunately, the growth in the level of exports as a proportion of GDP in the UK has been the weakest of all these economies over a prolonged period. Exports have risen faster than UK GDP, but much less strongly than in other economies. Exports have not contributed as much to UK growth as they have in other countries.

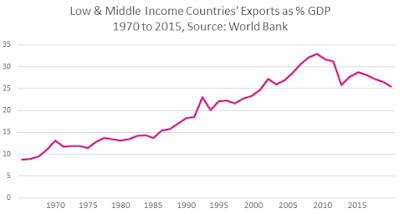

To avoid any misunderstanding that the growth of exports in these economies has been at the expense of other, poorer countries, Chart 1 below shows the proportion of exports in the GDP of all Low and Middle Income Countries over a similar period 1970 to 2015. Exports have risen strongly as a proportion of GDP for all Low and Middle Incomes in aggregate. Exports comprised 8.8% of GDP for this group of countries in 1970 and this had risen to 25.5% of GDP in 2015. This represents a rise of 290%. Low and Middle Income Countries have also experienced export-led growth. Of course, as with other countries this has declined from 2007 onwards as part of the Great Recession.

It is only possible for the whole world to experience rising exports as a proportion of GDP if world trade grows faster than world GDP. This in turn implies that exports lead GDP growth and, furthermore, that the greater the participation of an economy in growing world trade the faster it will grow, all other things being equal.

This corresponds to the most fundamental laws of economics. These were first elaborated by Adam Smith in ‘The Wealth of Nations’, where he sets out what he describes as the division of labour as the most fundamental force in developing the productive level of the economy. This concept was itself developed by Marx in Volume I of ‘Capital’, where the socialisation of production brings in all the productive forces of a society, capital in all its forms as well as land and labour. For Marx, the motor force of economic development is the socialisation of production and is the economic basis of socialism, the integration of all production determined by the needs of society as a whole.

The growth of trade at a faster rate than GDP is just one aspect of the overriding importance of the (international) division of labour, or socialisation of production. Another is the growth of the capital stock (Marx’s ‘organic composition of capital’) at a greater rate than GDP, which is why the rate of investment is the second-most important factor in determining growth. A further factor is the importance of education, as labour becomes increasingly skilled in order to function in an increasingly complex and interconnected, or socialised economy.

This socialisation of production means that inputs grow faster than outputs. These inputs include both capital, including fixed capital and circulating capital, as well as the inputs of labour, both the numbers in work and their levels of skill and education.

All the preceding points made in relation to exports apply equally to imports. Indeed, they have to as the sum of world exports must equal the sum of world imports, even if the statisticians struggle to align the two.

It would be one-sided and so false to examine only the growth of exports. Imports necessarily grow at the same pace, at least on a world scale. In addition, because production is increasingly socialised, it is necessary to import in order to export.

In general, the largest Western economies and the most productive are highly dependent on imports in order to export. The import content of exports tends to be around 25% of the total. According to the OECD in 2011 the import content of exports was 28.2% of the total. For the OECD as a whole, even in the relatively short period 1995 to 2011 the import content of exports has risen from 14.9% to 24.3%. This is shown in Chart 2 below.

Just as both exports and imports are rising faster than GDP, the import content of exports is also rising even faster than exports/imports themselves. So, the import content of exports is the fastest-growing aspect of the all the OECD economies’ growth. This provides a clear indicator that inputs grow faster than outputs, and that the socialisation of production is a fundamental factor in the development of the productive capacity of the economy.

There are a number of consequences that flow from this factual and theoretical analysis. One of them is that the idea of a national-based economic revival is a pipedream and that restricting imports in an advanced economy in order to boost economic activity is a backward-looking fantasy. It would cut any an economy off from the most advanced technologies and the integrated supply chains which increasingly determine world economic activity. Therefore, for any economy the key task is ensure its optimal insertion into the world economy under the most advantageous circumstances.

In addition, efficiency of all investment is a function of its access to the most productive (efficient) capital equipment in the world. A relatively poor country would be able to increase production much more effectively with access, say, to the most advanced harvesting machines, than if it expended far greater sums in creating its own inferior equipment. This is the same analogy as Adam Smith’s pin maker transposed to a national or international scale. (Although for a developing economy a period of protection for one or two sectors may be necessary or desirable as they ready to enter the world economy).

The contrary policy where import substitution is the dominant trend has been tried and failed miserably on numerous occasions. The collapse of Argentina’s relative economic wealth under Peron and others, or the stagnation of Franco’s Spain all testify to the bankruptcy of this policy when it is adopted wholesale and pursued vigorously. The modern exemplar would be North Korea.

The UK example

Data already shown in Table 1 indicate that the UK economy had by far the greatest proportion of exports in GDP of any of the major economies in 1970. It still has one of the larger export shares of the leading economies but it has experienced a sharp relative underperformance of its growth compared to other countries.

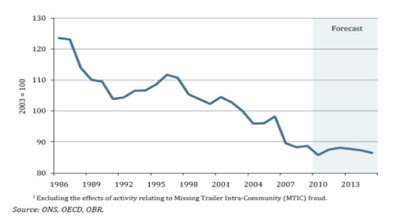

Chart 3 below shows the sharply declining UK share of world exports markets and the Office for Budget Responsibility’s own assumptions of further decline. In the index the 2003 level equals 100. The data are stark, showing that the UK’s export share of world trade has fallen by 30% in 30 years.

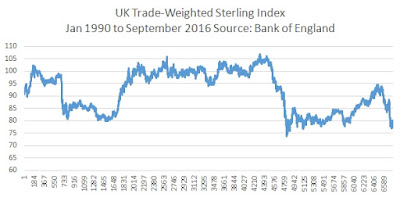

Throughout the crisis a number of ideas have been advanced regarding both its source and the cures. However, many of these are simply incapable of addressing the chronic decline in export competitiveness. The notions that the UK could reverse its plummeting export performance by monetary measures, or by reversing ‘financialisation’, or by boosting ‘demand’ or by tax reform, however laudable they may be in themselves, are frankly silly.

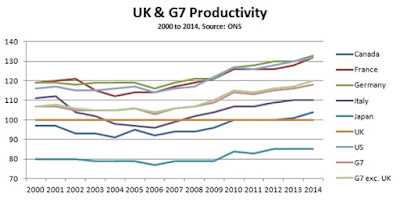

The crisis of British export performance is a crisis of competitiveness brought on by lagging productivity. This is itself is caused by very low relative levels of UK investment. With the exception of Japan, the rest of the G7 countries have higher productivity than the UK. France, Germany and the US are all more than 30% more productive, as shown in Chart 4 below.

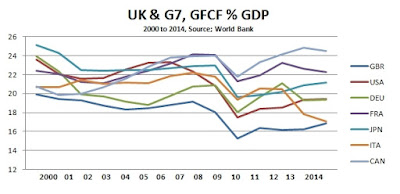

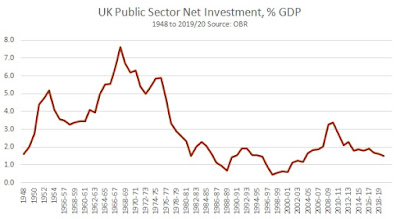

Productivity, output per hour worked, is determined by the amount or sophistication of machinery and equipment in the production process, as well as the skills of the workforce. More or better machinery requires investment. This in turn is a function of the level of investment, both in capital and in the skills and education of the workforce. Taking only the former, it is easy to see why UK productivity languishes so lowly in the international comparisons and why its export growth has been so limited. Chart 5 below show the proportion of GDP devoted to investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) in the G7 economies (of course the level of Chinese investment and its export growth are considerably higher).

In 2014 the proportion of GFCF in UK GDP was just 17%, compared to over 21% for the G7 average. Simply in order not to fall further behind would require increasing UK investment by approximately 4% of GDP, or £75 billion a year. To actually begin to close the productivity and competitiveness gap would require significantly more, at least £100bn additional investment per annum. This is the task facing the UK economy if policy is aimed at benefitting from the growth in world trade.

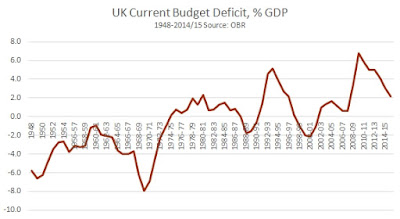

The apparent Tory Party U-turn on public investment is in reality a purely rhetorical one. In his day Osborne too was fond of donning a hard hat and talking about investment. But under current plans public sector net investment is due to reach new all-time lows under this Government. The £2 billion promised for housing builds very few houses and does not register at all in measures of investment as a proportion of GDP.

Separately, the accumulation of all investment (the capital ‘stock’-Smith, the ‘organic composition of capital’-Marx) is itself dependent on the size of the market. What has become known as ‘economies of scale’ is in reality the level of productive capital appropriate to the scope of the market in which it operates.

The largest market in which the UK economy can operate with its current level of productive capacity is the EU. If it were going to flourish in a global market it would need to compete with countries such as India or China, where investment as a proportion of GDP ranges from 33% to 43%, led by state investment, which no-one intends.

Conclusion

Therefore, given current levels of UK investment membership of the EU and single market is vital to maintain even the economy’s current level of integration in the international division of labour and into global supply chains. If other countries have higher levels of investment, UK levels of wages will converge to their level simply in order not experience a catastrophic loss of competitiveness.

This analysis also highlights the scope of the challenge facing the next Labour Government. £75 billion a year in public sector net investment and rising is required simply in order not to experience further declining competitiveness. Membership of the EU and the Single Market are both vital to medium-term economic prospects. Otherwise, the long-term relative decline of the UK economy, its productivity and living standards will continue.

Recent Comments