Budget shows women bearing the heaviest burden of austerityBy Kerry Abel

This government’s budget and the entire austerity policy hits women harder than men. At the same time the government are consulting on gender pay gap reporting, because as they acknowledge, the gap between men’s hourly pay and women’s still stands at 19.2% the Tories are taking 81% of their budget cuts out of women’s pockets.

Despite making cuts to local government, the NHS and other public services in the period 2010-15, including £200billion from the NHS the Chancellor has not met his target to balance the books by 2015, so has come back for more. And they are taking from those least able to afford it. According to the Women’s Budget Group, households on the lowest incomes lose out five times as much as richest households.

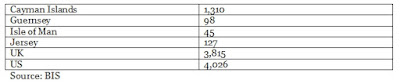

Fig.1 Cumulative impact of tax/benefit and spending cuts by income decile (2010-20)

Graph from: A cumulative gender impact assessment of ten years

of austerity policies, published by Women’s Budget Group

This was not neutral budget. Women tend to be in the lowest paid sections of society, more likely to be on the minimum wage and have to stretch their wages further – 90% of single parents are women. The budget’s tax cuts mainly benefit rich men because they are disproportionately high paid. Analysis by the Tax Justice Network noted before the budget that ‘if George Osborne slashes the rate further in the Budget – from 45p to 40p for those on £150,000 or more – will put even more money in men’s pockets’.

How does this work?

The first channel for the uneven distribution of austerity is the aim of cutting public sector spending by £3.5 billion by 2020. The public sector – local government, schools and hospitals are disproportionately staffed and used by women. So any cuts will affect women’s employment prospects more as well as leaving them holding the baby, the disabled relative or older family member when a cut to a service bites.

Public sector workers have had only a 1% or less pay rise in the last five years and four more years is a real terms cut of 15-20% of their wages.

The government has outlined £3.5bn additional cuts to departmental budgets – excluding those protected areas of education, health, international aid and defence – which will need to be found in 2019/20, budgets that will have already fallen in real terms by over a third since 2010.

2019/20 will also be the same year that public sector employers will be faced with a £2bn increase in contributions to unfunded public sector pension schemes, which arises from the update to the discount rate applied to pensions. The Nuffield Trust estimate that this could mean a £650 million bill for the NHS virtually wiping out the marginal 0.7% spending increase planned for that year and leading to a real terms cut in health spending in that year.

Public sector employers will also be struggling to meet additional National Insurance contributions as a result of the abolition of the second state pension, a figure just shy of £3bn. With a cap on public sector pay due to remain until 2020 and the government already committed to further savings on redundancy pay and sickness absence, it is hard to see what more can be squeezed out of a public service workforce that is beset by increasing recruitment and retention problems.

This can be broken down even further in terms of health, education and wages. In November the Health Foundation analysis showed the government commitment to increase NHS funding by £10bn in 2020/21, but this is only an increase to the NHS England budget not total health funding. The NHS has been creaking under the pressure of the last parliament’s cuts and increased pressures on health spending arises from demographic changes and cuts to other budgets, especially social care. So some vital investment has been cut and will not be restored by this budget – junior doctor training, health visiting, sexual health and vaccinations are all at risk and hospital equipment neglected over the last five years.

Money has now been allocated to local government to spend on health and this is open to politicisation and inefficiencies, the postcode lottery of contraception availability is a prime example of this. But it is also a false economy, for every £1 spent on contraception the NHS saves at least £11. The Advisory Group on Contraception research found that the average abortion rate was around 9.7 per cent higher in areas where services were restricted, compared with areas with no restrictions. And some centres like the newly refurbished Margaret Pyke centre is faced with closure despite significant investment in 2013.

Health cuts affect care services and women suffer disproportionately and end up have to bear the burden when the state fails.

There has rightly been a campaign against and media outcry about the announcement of forced ‘academisation’ of all schools by 2020. There will be a wholescale move away from the national curriculum and the nonsensical idea that parents should not have a say in how the school is run. But this will also affect how staff are paid and how that pay is collectively negotiated. The compulsory move to academies is an attack on collective bargaining, which will result in less fair and transparent pay structures and this will affect women’s pay. Collective bargaining helps to create pressure for remuneration decisions to be fair and transparent, that starting salaries are fixed, that maternity pay is the same across the country and that teachers and school staff know they are being paid a fair rate for the job. Anything that undermines this opens up multi-tier pay deals that will leave those in rural or difficult schools less well paid. Wherever collective bargaining has broken down, women’s pay suffers.

It is shameful that the gender pay gap still exists and currently stands at 19%. The biggest single policy that closed the gender pay gap was the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1999 and reorganised public sector pay in the 2000s as part of large scale pay and grading programmes went some way to close the pay difference, but in recent years it has stagnated. Women are at the poorest end of the wage scale and the case for equality is not taken seriously enough. Legal requirements for policies to have no detrimental impact on equalities are routinely ignored, despite many commentators highlighting this issue.

The increase in the new National Living Wage is important and 61% of beneficiaries are women. Job growth is important, but women are disproportionately in low paid part time jobs (75% of part time workers are women). The move to low paid, zero hour contracts and spurious self-employment in unstable working environments is not the solution.

On top of this, the TUC have repeatedly pointed out that the ‘motherhood penalty’ still exists, by the age of 42, mothers who are in full-time work are earning 11% less. It is still culturally linked to the idea that men should be the breadwinners, and that women are seen as less committed to work when they return as parents. Research in America found that changes in work behaviour and time out of the labour market may explain some of the motherhood pay penalty but the majority is unexplained.

Unfortunately none of this will be properly dealt with by the gender pay gap reporting proposals from the government, currently being consulted on, due to come in from 2018 because the reporting system is voluntary and companies are not required to give information detailed enough to shine a light on the main causes of the overall gender pay gap within their organisation.

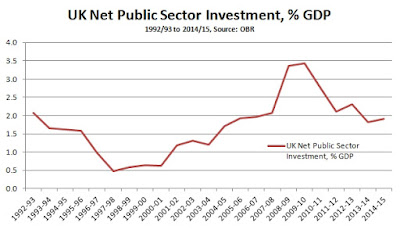

Cameron and Osborne often argue that strong public services like the NHS require a strong economy. But SEB has shown that their central policy of cutting taxes on profits and on high earners has not produced a strong economy. Business investment as a proportion of GDP was higher when the Corporation Tax rate was 30% than it is now with the rate at 20%. Capital gains tax is also down, the higher rate is being reduced from 28% to 20% and the basic rate from 18% to 10% – this is what led to private equity partners paying a lower rate of tax than their cleaners.

It is true that raising the tax free personal allowance will benefit low income women lifted out of paying tax but it disproportionately benefits higher earners and doesn’t help those who already earn less than the threshold. Quite simply these measures mainly benefit double income households where both are high earners.

The reality is that austerity constitutes both a frontal assault on public services and has led to economic stagnation. Under Cameron and Osborne, neither the NHS nor the economy is strong. And, because of the greater exploitation of women and their oppression, they bear the greatest burden of this.

In effect, the Tory policy is to cut pay and public spending in order to fund tax giveaways for businesses and the rich. It is a policy that disproportionately hits women and benefits only the tiniest fraction of society. It isn’t working. There is a clear alternative based on investment in the economy for sustainable growth. The benefits of that growth can be directed to protecting and rebuilding out public services, and so ending the Tory offensive against women.

Recent Comments