The Corbyn Government and the private sectorBy Tom O’Leary

There has been a furious and ill-informed reaction to comments by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell regarding the pharmaceuticals industry. This follows a renunciation of Corbynomics by the well-known blogger Richard Murphy. Both cases illustrate widespread confusion on the left and on the centre of British politics about the economy and its driving forces. Confusion is never helpful, and may be highly damaging and so it should be ended.

The central problems of British politics are that the Tory Party believes it understands the fundamentals of economic policy and that many on the Labour side share this high opinion the Tories hold of themselves. The fact is that the Tory Party has been in office for the overwhelming majority of the last 150 years in which time Britain has experienced a continuous relative economic decline without precedent in the modern era.

The Tory notion, that as business runs the economy then whatever business wants must be good for the economy, has been maintained throughout this decline and is even used as a justification for it. It is claimed that alternative policies would have been worse despite the mass of evidence provided by other countries who have experienced an enormous advance in their relative economic weight in the world economy over the same period. In economics, the Tories forget nothing and have learned nothing. It is not possible to offer economic solutions to the current crisis by mimicking them, as many in the Parliamentary Labour Party wish to do.

Corbynomics in government

The purpose of a political party is not to strike a pose or make propaganda but to wield power in support of the interests it serves. Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell reject the failed Tory nostrums of austerity, under-investment and chronic decline. In the economic sphere their aim is to achieve office in order to boost the living standards of the population, address key threats such as climate change and inequality and to ensure that the overwhelming majority of the population enjoy a far greater share of the wealth they create.

The context for this programme is that the private sector is the dominant component of the economy in Britain and will be for the foreseeable future. But the foolish Tory/Labour right notion that everything the private sector wants should be delivered is blatantly false in the era of the Panama Papers, Mike Ashley and Philip Green.

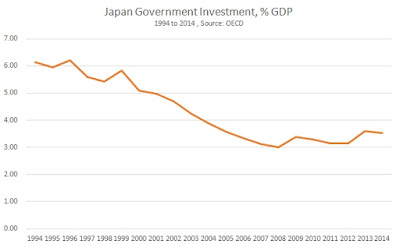

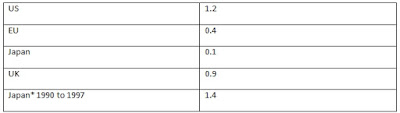

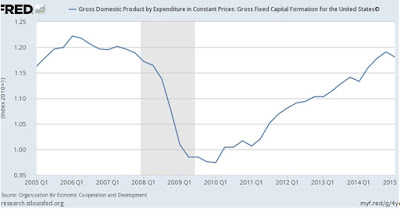

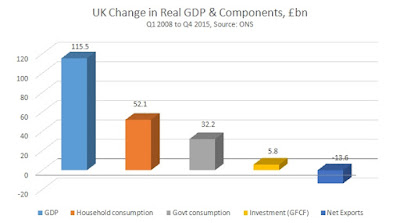

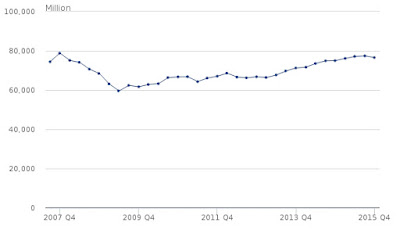

Instead a sober assessment is required of the strengths and failings of the private sector and government intervention should obviously be designed to strengthen the former and correct the latter. Overall, the current crisis was caused by the failure of the private sector to invest and has been extended by their continued refusal to organise an investment recovery.

There is a list of industries in Britain that have completely failed to deliver the necessary level of investment. There is a homebuilders’ sector which builds no homes, an energy sector which is keener on pollution through fracking than investing in renewables and which has led to power shortages being officially predicted this winter, and a set of railway companies which couldn’t run a whelk stall despite receiving a bigger government subsidy than British Rail. Crucially, Britain now has the highest level of charges for higher education in the world and yet a below-average attainment of a Master’s degree or above in the OECD.

The essential approach to these industries is that the private sector has failed to invest so that the public sector must. In some cases this means (re)nationalisation. But in all cases it means that the public sector regulates the level of investment at a much higher level and that the benefits or returns on this investment must also accrue to the public sector in order to be sustainable. This means the government or local authorities and others building homes. It means the state investing in renewable energy and energy storage and levying the energy sector companies to contribute to that. It means taking over the train operating companies and boosting investment via Network Rail. In education it means scrapping fees and raising the universities’ budgets so that they can increase their level of R&D and investment.

There is a separate category of profitable industries, many of whom employ large and well-paid workforces. These include banking and financial services, the military sector and pharma. There are others. Even here spectacular failure is possible so that nationalisation is unavoidable, such as Lloyds and RBS banks or potentially a large chunk of Rolls Royce. But in all cases the role of a radical government of the left is to harness those industries for productive use. This includes directing them towards useful new activities and ending subsidies and tax breaks for useless or harmful activities, using public purchasing, tax changes, regulatory measures and legislation to promote useful investment and deter damaging activities. To take just one very simple example, George Osborne cut tax credits for business investment in 2011 to in order to fund a cut in the rate of Corporation Tax. This is a net benefit to companies that do not invest at the expense of those who do, and should of course be reversed.

Harnessing these industries for productive use means banking becomes a channel for investment not speculation, the defence industry shifts into civilian use technologies such as industrial hardware, scientific research, civilian marine, aerospace and satellite production and so on. For pharma this means shifting R&D from ultra-expensive questionable palliative and non-essential drugs towards effective generic drugs and drugs to tackle the big global killers, malaria, heart disease, HIV/AIDs and so on which are currently neglected. In this way pharma is subordinated to the NHS and global health needs. For each of these industries there will also be strong benefits through government increasing its own funding for investment.

A third group of industries are mainly in the retail or service sectors, everything from real estate activity, to the leisure industries to personal services such hairdressing and high street shops. This group also increasingly includes functions such as social care and others formerly carried out by the public sector which have been outsourced to the private sector. Many, not all, of these are low-paid jobs. The role of government is to ensure that they are properly regulated, both in terms of staff and in terms of their customers. The National Minimum Wage, the fight for pay and job equality for women, black people and others and all forms of worker protection should be rigorously enforced across all sectors, but these are the sectors which include the most egregious employer offenders. Childcare needs to be placed on a well-funded collective enterprise, not a ramshackle and over-priced home industry as is currently the case.

Across all sectors the principles are to use whatever is the most effective lever to increase the level of the investment in the economy and ensure that the benefits of that are shared more equally among the overwhelming majority of the population. People’s Quantitative Easing, a National Investment Bank and regional offshoots, increased borrowing for investment all means to achieve that end. The state must aim to regulate the level of investment in the economy and that level must be much higher than currently. This is the road out of the crisis.

Recent Comments